I. Introduction

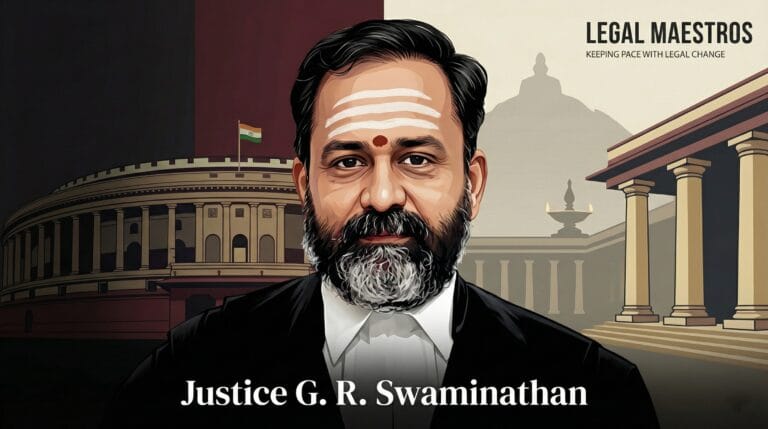

The recent impeachment motion moved by INDIA bloc along with DMK in the parliament against Justice G.R. Swaminathan a sitting judge of Madras High Court sets a consequential moment in India’s constitutional history. While impeachment is a constitutionally granted motion but it is a rarely used power due to the fear of execution using it as tool to supress judicial independence. The present controversy arose out of judicial orders connected to the Thirupparankundram Karthigai Deepam dispute in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, it raises various questions related to not only single hilltop’s controversy but the state of affair in Tamil Nadu and the balance between executive’s tug of power with judiciary.

At its core, this episode presents a fundamental constitutional dilemma: Does the impeachment motion represent legitimate judicial accountability, or does it signal a dangerous politicisation of constitutional mechanisms meant to protect, not intimidate, the judiciary?

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

This article will try to deep dive into legal, social, political landscape of the Deepam row in Madurai and assess its wider implications for the independence of judiciary and doctrine of separation of powers under the Constitution of India.

II. Factual Matrix of the Controversy

The dispute has its origin to as back as to British era, the issue revolves around Karhigai Deepam ritual at Thirupparankundram Hill near Madurai, a site which is religiously significant to both Hindus and Muslims. The recent reason why this controversy took air was due to a judicial order permitting the lighting of the scared deepam at a specific pillar (Deepathoon) situated near the dargah, following these allegations the state authorities of Tamil Nadu had obstructed the ritual.

Generally, these issues remain significant to the regions where they arose but this controversy took over national limelight due to political mobilization, and competing claims over the judicial order into a centre of communal and political contestation. Soon after this, over 100 MPs of INDIA bloc and DMK of TN submitted a notice seeking the removal of G.R. Swaminathan, alleging judicial overreach, ideological bias, and conduct unbecoming of a constitutional office holder.

The transition from courtroom adjudication to parliamentary impeachment is what renders this episode constitutionally significant.

III. Constitutional Framework for Judicial Removal

The Indian Constitution provides for the removal of judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts under Articles 124, 217, and 218, read with the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968. A judge may be removed only on grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity, following a rigorous, multi-stage process involving parliamentary scrutiny and a judicial inquiry committee. The motion must be first admitted by the Speaker after scrutinising it only if admitted this process moves forward to Constitution of an inquiry committee and subsequent voting in parliament; which requires special majority in both houses.

Crucially, constitutional jurisprudence has consistently maintained a clear difference between judicial error and judicial misconduct due to bias or any other reasons. Errors in interpretation or reasoning are addressed through the mechanism of appellate remedies not through the step of impeachment of the judge concerned. Removal is sought only in the rare cases of moral or functional bias of the office holder.

The historical rarity of the impeachment motion in India reflects the institutional restraint aimed to preserve legal sanctity of judiciary and independence, the attempts made in past have either failed or been withdrawn.

IV. Political Landscape: Legislature versus Judiciary

This motion of impeachment is being criticised by people of various social and political landscape due to its timing and the context in which the motion is brought, the motion is brought not because of the bias that the judge holds but rather the dissatisfaction of the legislation over the judgment. Many people from retired posts in legal fraternity have criticised this move because such motions may intimate the judges to pass on cases including sensitive matters.

What makes this matter worse is the fact that this motion is rooted less in clear cases of judicial bias but more on the fact that the State Government was dissatisfied with the judicial outcome which touched upon sensitive religious and political terrain. If legislation started acting on every dissatisfaction it has it will set a wrong precedent ad risks judiciary being subordinated to shifting winds of politics.

V. Social Dimensions and Judicial Independence under strain

Judicial intervention in disputes involving religious and shared sacred spaces, court inevitably while adjudicating matters of such dispute operate within a fragile social context. In a plural society such as India, courts are frequently called upon to adjudicate on issues involving intertwined faiths of different religious denominations. The Thirupparankundram controversy exemplifies how judicial determinations, even when grounded in law can become a centre of social and political mobilisation.

Public discourse in such cases is shaped more and more by media and less by legal reasoning. The two sharp edged opinion of the public on this matter which is either that the court acted by asserting religious freedom or an act threatening communal harmony highlight the fragile social ecosystem within which the courts operate.

However, making this dispute political risks putting judges in a difficult spot. They are expected to resolve constitutional issues while dealing with intense social pressures. They also face the added risk of political backlash after the fact.

VI. Accountability versus Intimidation: The Core Legal Dilemma

The main legal question is not whether judges should be held accountable they definitely must be but rather how that accountability is carried out. Impeachment is intended by the Constitution as a last resort rather than a quick fix for disciplinary issues.

The constitutional framework and judicial finality are both compromised by turning impeachment into a substitute appellate process. Mechanisms for judicial accountability must be institutionally insulated, impartial, and proportionate. If not, the very procedure designed to uphold constitutional principles runs the risk of turning into a weapon of intimidation.

This caution is reinforced by comparative constitutional practices in other democracies. Impeachment is rarely used in developed constitutional systems because of its potential for instability.

VII. Conclusion

The current controversy highlights the urgent need for clearer parliamentary rules on starting removal motions. We must have procedural safeguards to make sure impeachment is separate from political interests. At the same time, we should strengthen judicial accountability mechanisms. Transparent in-house inquiries can build public trust without harming independence. Institutional dialogue should guide relations between branches, rather than confrontation.

The impeachment notice related to the Thirupparankundram Deepam controversy is less about one judge or one order. It is more about the future of India’s constitutional democracy. This situation tests the strength of institutional boundaries and the level of political restraint.

Whether this episode turns into a constitutional mistake or an alarming precedent will depend on how Parliament, the judiciary, and civil society react. The stakes are high; it’s not just about judicial accountability, but also about maintaining the constitutional balance that upholds the rule of law.