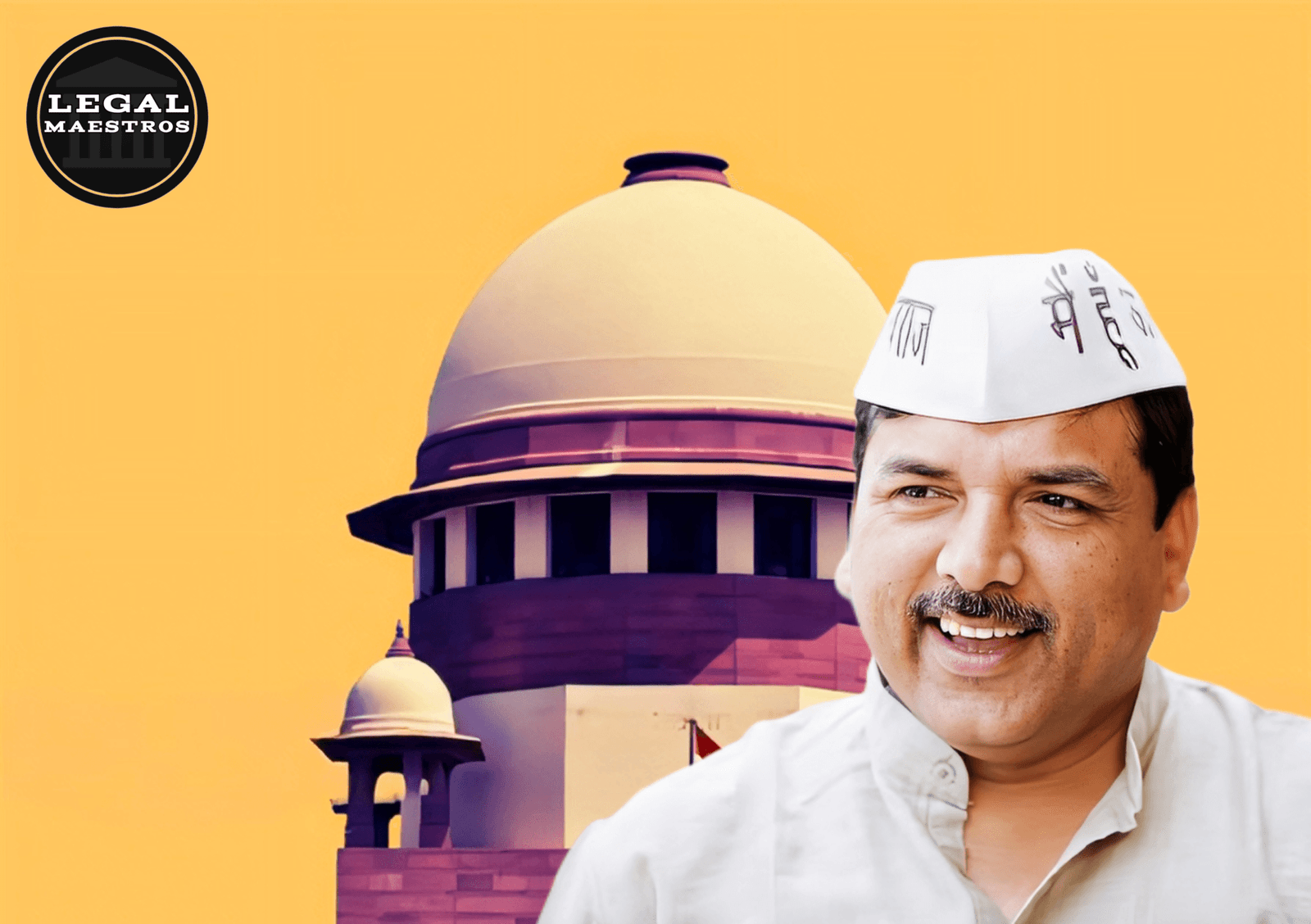

With the recent move of the Supreme Court to reject a roding in the case by AAP Member of Parliament, Sanjay Singh challenging the Uttar Pradesh government move to shut down 105 primary schools prompts serious concerns over the legal framework of the matter, government policy and the enshrined connected right to education. This article will disperse the legal and constitutional profile of this case, stating the reasons of why Supreme Court did not interfere and what it implies to the future of public education in India.

Background: The Case and The Dispute

In June 2025 the Uttar Pradesh government passed an order that 105 government run primary schools would be merged or shut down. This was done based on the fact that these schools did not have students or few students in the government. The government argument is that such a decision, which it refers to as school pairing, forms part of a wider initiative to utilize resources in a more productive way and to enhance the quality of education, a move it says is in sync with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

Sanjay Singh in his petition under Article 32 of the Constitution put forward the case that decision by the government was arbitrary, unconstitutional and legally not permissible. The destruction of these schools was directly against the right to basic education enshrined to each and every child in India and this was his main point.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Right to Education: The Legal Axiom

Education is a very powerful legal right in India. It is not only a policy, but a basic right.

- Article 21A of the Constitution: This is the most crucial constitutional act of law regarding the same. The 86th Amendment inserted it into the Constitution in 2002. This is prescribed: “The State shall endeavour to provide a system of free compulsory education to all its children of the age of six years to fourteen years, in such manner as the State may, by law, determine.” The government under this article makes it constitutional obligation to show free and compulsory education to children of the same age period.

- The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009: An Act formulated to give consent to Article 21A. The RTE Act gives the legal framework as to the implementation of this right. It establishes particular regulations and guidelines on schools. An instance is that according to it a primary school of classes I to V should be within 1 kilometer of all residential places with a population of not less than 300 persons. This is the rule of the neighborhood school.

The petition filed by Sanjay Singh stated that closing schools were violating these provisions of law as argued by the Uttar Pradesh government. The closures, he argued would compel children to commute farther and this might result in them leaving school particularly the children in poor families, Scheduled Castes and girls. He further stated that the move by government was an executive order which was not legally supported.

Position of the Supreme Court: The Reason Why it Wouldn Intervene

However, the Supreme Court in this case refused to hear the case of the petitioner, although the views presented by the petitioner are very persuasive. It was argued in this decision within the main principle of the judicial practice and distribution of powers among the courts.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

- The Principle of Judicial Restraint: India has the highest court Supreme Court of India. But this is not understood to mean that it hears all the cases. The Indian legal system has a well defined lay out of the establishments which begins first with the lower courts, secondly with the High Courts of each state and at the apex is the Supreme Court. It is common in the Supreme Court that issues which have a local nature and which do not apply nationwide, should be heard in the first instance by the High Court of that state.

- Jurisdiction and Article 32: Article 32 of the constitution was invoking article when filing the petition. In this article, an individual can directly appeal to the apex court; that is, the Supreme Court, in the event of a violation of his fundamental rights. Although this is a potent weapon, the Supreme Court has frequently ruled that the petitioner must proceed to a High Court when the matter to be tested involves a proper legal redress; otherwise the petitioner is required to approach a High Court first and only after that a High Court should issue a certificate to approach the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution. In this regard, the Supreme Court observed that other legal controversies regarding the school closings had been scheduled to be considered by the Allahabad High Court.

- In the Story of the High Court: A bench led by Chief Justice Dipankar Datta with Augustine George Masih said it is a case of a local problem and not a matter that had over soured to other states. They argued that the aspect concerned the exercise of the statutory rights under the RTE Act and the case was already before the Allahabad High Court and it was therefore preferable that the High Court hold its opinion therein. They accorded the petitioner the leave to withdraw his plea and to appeal to the Allahabad High Court, to redress them thus imploring that court to resolve the issue speedily.

Broader Legal argument: Policy (and fundamental rights)

There is always a conflict between the legal approach to this case: whether the government has the right to take the policy decision or it is obliged to safeguard the basic rights of individuals. This defense strategy by Uttar Pradesh government is that its policy on merger of schools is purely an issue of disposition and education reform that seeks to cut on quality and efficiency. They are also attempting to make intelligent use of the resources they have; this means that they are merging schools that have few learners.

But the legal question raised is, since such a policy although founded on the noblest motives is contrary to the express legal provisions of the RTE Act; does not the law demand that this policy should not be adopted? The Act requires a so-called neighborhood school and does not define any minimum student amount to have a school. The gist of the case law is that even when the government proposes to do something that intrudes on a fundamental right, it cannot give a starting point by referring to its proposed action as a policy decision.

So What?

It is not a case of the Supreme Court making any judgment on legality of the action of the Uttar Pradesh government. It is a determination of what court to serve the case. It is now up to Allahabad High Court ball. The High Court will be put to the task of weighing the considerations given by both parties. It will have to ascertain:

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

- Is the order of the government of Uttar Pradesh to shut these schools a contravention of the neighborhood school rule of RTE Act?

- Does the action of the government, in this particular case, involve a refusal of a child to have right to free and mandatory schooling?

- Does a government policy have the power to dominate over a basic right and a particular act such as the RTE Act?

The case decision made at the Allahabad High Court will reflect quite substantially on law. It will provide precedence on the extent that a state government can go in offering educational reforms especially when the reforms result in the deactivation of schools. It is set to be one of the critical tests on courts holding together the administrative authority of the government, against the constitutional and statutory interests of children.

To conclude, the Supreme Court has decided to take a back seat as of now but the legal battle of closing the schools is still not over yet. It helps emphasize the fact that education in India is a statutory right and any government interference in regard would have to pass scrutiny of the law and the Constitution.