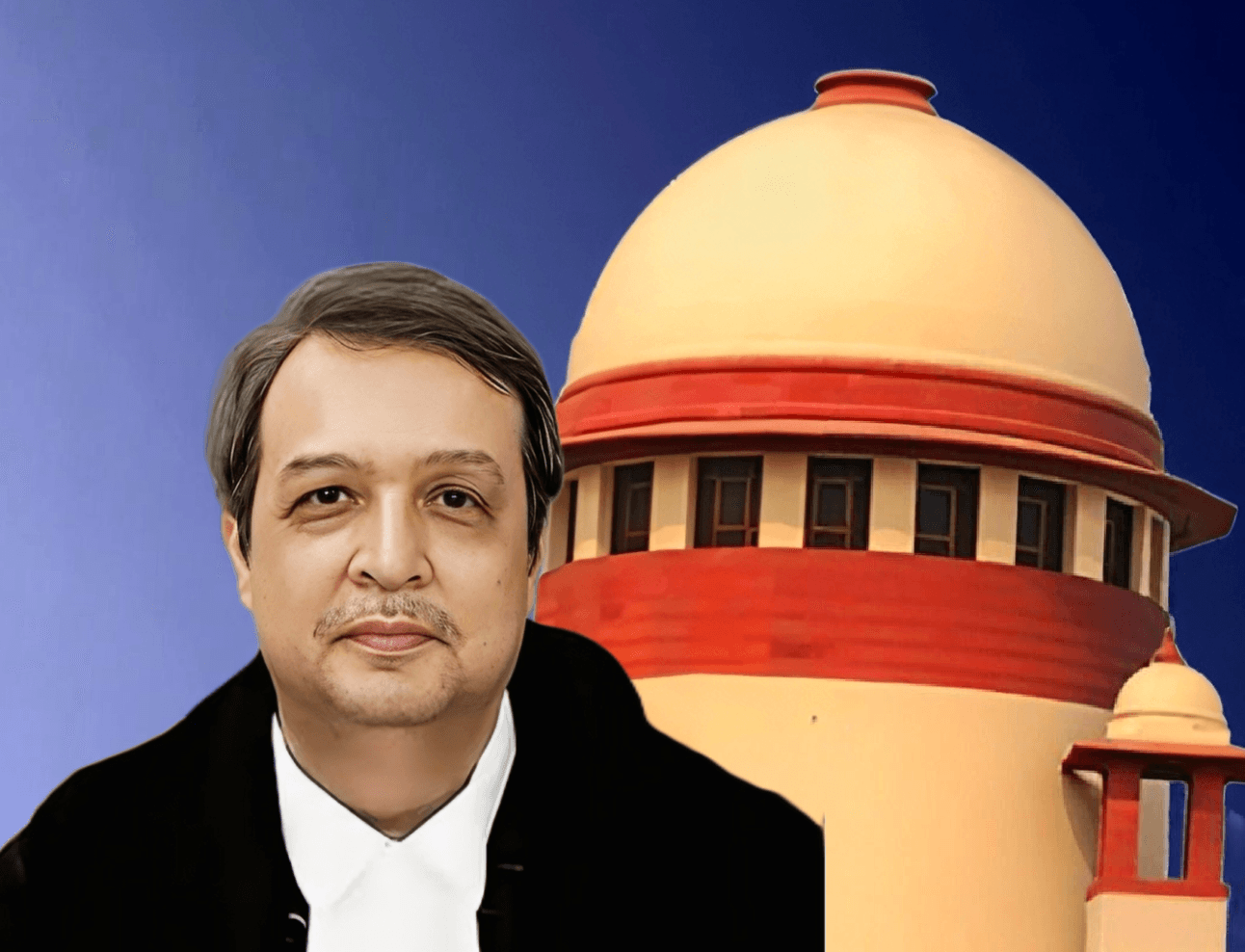

On April 17, 2025, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, with Justice J.B. Pardiwala giving the main decision, concluded two merged appeals that had been brought before the High Court of Delhi.

The Drugs and Cosmetics Act was challenged by the DRI, which contested judgments that discharged accused individuals from NDPS charges related to Buprenorphine hydrochloride, which is a psychotropic drug that is included in the NDPS Act but is not included in Schedule I of the NDPS Rules. Additionally, the DRI attacked orders that remitted the cases to trial.

An Overview of the Facts

On September 27, 2003, DRI investigators conducted raids in New Delhi and Haryana, collecting over 40,000 ampoules of Buprenorphine hydrochloride without a license.

This incident is documented in Criminal Appeal 1319/2013. The three respondents made statements of their own will that implicated them in unlawful manufacturing, storage, and distribution in violation of Sections 22 and 29 of the National Defense Police Act. During the month of February in 2005, the Special Court formulated the charges.

DRI recovered 50,000 ampoules from a dealer in Criminal Appeal 272/2014. The dealer acknowledged to selling 250,400 ampoules without sufficient records in violation of Rule 67 of the National Drug and Poisoning Statistics Rules.

In May of 2005, a charge was drafted in accordance with Section 22(c) of the NDPS Act. In both cases, the High Court decided that while buprenorphine hydrochloride was classified as a psychotropic drug under the Act’s Schedule, it was not included in Schedule I of the Rules, and as a result, it did not fall within the constraints of Chapter VII’s ban guidelines. Under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, the proceedings were routed to be tried in a different court.

Framework of Statutory Law

Any person is prohibited from trading in “any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance” according to Section 8(c) of the NDPS Act, with the exception of those who are engaged in the activity “for medical or scientific purposes and in the manner and to the extent provided by” the Act or its Rules.

It is clear that the term of “psychotropic substance” under the Act encompasses all of the substances that are included in its Schedule, which includes buprenorphine hydrochloride. A clarification is provided in Section 80 that the requirements of the NDPS are “in addition to” the Drugs and Cosmetics Act.

Courts are granted limited authority to modify or erase charges under Section 216 of the Criminal Procedure Code; nevertheless, discharge after framing is not permitted.

Concern No. 1: The Range of the NDPS Act’s Section 8(c)

The most important issue was whether or not the act of dealing in a material that is included in the Act’s Schedule but is not included in the Rules’ Schedule I is considered to be beyond the scope of Section 8(c).

DRI contended that the simple wording of Section 8(c) encompasses all psychotropic chemicals that are included in the Act’s Schedule, and that the Rules under Chapter VII only regulate licensing process, rather than explicitly prohibiting the substance in question. The individuals who responded argued that since they were not included in Schedule I, they were subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act.

The Court’s Evaluation

The preamble of the Act was scrutinized by Justice Pardiwala, who raised an objection to the diluting of the strict regime that was supposed to discourage illegal trafficking. He came to the conclusion that Section 8(c) of the Act bans dealing in any psychotropic drug that is included in the Schedule, unless the transaction is covered by a medical-scientific exemption and that it is in compliance with the licensing rules.

By highlighting the fact that Rules 66 and 67 apply to “any psychotropic substance,” he rejected the High Court’s restrictive interpretation of Section 8(c), which claimed that it only applied to substances that were included in Schedule I of the Rules.

Sanjeev Deshpande’s Potential Impact on the Future of the Organization

In the appeals, the question was whether the case Union of India v. Sanjeev V. Deshpande (2014), which established that Section 8(c) applies to all drugs that are scheduled under the Act, should be applied prospectively, with previous decisions being unaffected.

The Supreme Court, using established principles, came to the conclusion that overruling rulings are implemented retroactively in the absence of an explicit direction. Deshpande’s view is thus the one that controls these appeals.

Section 216 of the Criminal Procedure Code and Charge-Framing

Respondents filed a motion under Section 216 of the Criminal Procedure Code to remove NDPS counts, stating that no offense had been established during the investigation. The application was granted by the Special Judge, and the High Court’s decision was upheld.

It was made clear by the Supreme Court that Section 216 cannot be used to secure discharge after the court has reached a prima facie determination of satisfaction. Changes made in accordance with Section 216 are restricted to clerical or formal corrections, and do not include deletions of substantial content after frame.

In DRI v. Raj Kumar Arora, the execution of the NDPS is realigned with the objective of the legislature.

It reaffirms the expansive scope of Section 8(c) to include all psychotropic chemicals included in the Act’s Schedule, compels the application of Deshpande in retrospect, and prevents the exploitation of Section 216 of the Criminal Procedure Code after it has been framed. This ruling improves the deterrent nature of the Act and guarantees that international responsibilities are applied in a consistent manner.

For any queries or to publish an article or post on our platform, please email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

1 thought on “Reconciling Regulation and Rights: Justice J.B. Pardiwala Judgment in DRI v. Raj Kumar Arora”