In the case Satish Chander Sharma and Others v. State of Himachal Pradesh and Others, the Supreme Court of India reiterated a fundamental concept of constitutional law. This principle states that final decisions, particularly those from the highest court, cannot be re-litigated in accordance with Article 32 of the Constitution.

A repealed program was the subject of the petitioners’ request for equity in pension payments. The petitioners were retired public sector employees. The court upheld its earlier verdict in the case of State of Himachal Pradesh v. Rajesh Chander Sood (2016), which resulted in their effort being categorically denied.

Historical Context of the Case

The individuals who submitted the appeal were former workers who had retired from the Himachal Pradesh State Forest Development Corporation Limited. They decided to go with the Himachal Pradesh Corporate Sector Employees Pension Scheme, 1999, which offered retirement benefits that were comparable to those offered to state government employees. Nevertheless, a notification issued by the government on December 2, 2004, brought about the cancellation of this initiative.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators ) contact@legalmaestros.com.

Those individuals who had already retired between April 1, 1999 and December 2, 2004 were the only ones who continued to receive benefits after the repeal.

On that date, employees who were still working for the company were not eligible for the advantages of the program, despite the fact that they were a part of it. This resulted in protracted legal issues, one of which was a challenge brought before the Himachal Pradesh High Court, which initially found in favor of the employees.

However, in the case of Rajesh Chander Sood, the Supreme Court overturned the ruling of the High Court and maintained the constitutionality of the cut-off date, thereby stating that the repeal was within the authority of the law. That decision was challenged in the current case, which used Article 32 and raised charges of discrimination and the deprivation of rights that had been vested in the individual.

Important Legal Concerns

In this particular case, the Supreme Court addressed a number of important constitutional and administrative law concerns, including the following:

Whether or not the Writ Petition can be maintained According to Article 32

During the case of Rajesh Chander Sood, the Supreme Court made it very plain that its previous decision was final and could not be challenged once more through the use of a writ petition.

The enforcement of fundamental rights is guaranteed by Article 32, which is not a forum for reevaluating decisions that have already been made. When an issue is fully decided by the Supreme Court, it can only be revisited through the limited routes of review or curative petitions; a fresh writ is not permitted. This was confirmed by the Court. The use of this principle maintains judicial discipline and guarantees the finality of legal proceedings.

Whether or whether the verdict in the case of Rajesh Chander Sood was in accordance with the Incuriam

It was asserted by the petitioners that the earlier decision made by the Supreme Court was made per incuriam, which means that it disregarded precedents that were legally binding. The Court, on the other hand, categorically rejected this argument.

It was claimed that the earlier judgment had taken into consideration all of the pertinent legislation, such as pension rules and constitutional provisions, and that as a result, it was neither erroneous in law nor delivered without adequate reasoning.

Unvested Rights and the Withdrawal of Pension Insurance Scheme

The petitioners’ primary contention was that they had obtained a vested right to pension payments after opting into the 1999 program and giving up their rights under the Employees Provident Fund program. This was one of the most important arguments that they presented. The Court, on the other hand, maintained the previous finding that such a right is contingent rather than absolute.

It was noted that the program that was implemented in 1999 was a welfare project and did not generate rights that could not be revoked. Depending on the results of the administrative assessment and the financial feasibility analysis, the government maintained the authority to change or withdraw the scheme.

Proof that the cut-off date is valid According to Article 14

The individuals who submitted the petition contested the cut-off date of December 2, 2004, arguing that it caused employees to be separated into classifications that were arbitrary and unreasonable. In order to contend that such classification was in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution, they referred to the case of D.S. Nakara v. Union of India. However, the Court made a distinction in this particular case.

It was highlighted that although Article 14 forbids discrimination based on arbitrary criteria, a cut-off date that is determined by the ability to maintain financial stability is acceptable. The state had demonstrated, via the use of committee reports and financial statistics, that it was unable to fulfill its obligation to provide the benefits to all individuals. Consequently, the classification was reasonable and served a legitimate purpose throughout the process.

The Right to Property and Pension, as outlined in Article 300A

The rejection of a pension, which is considered a kind of property, is a violation of Article 300A of the Constitution, according to another argument placed forward. It was stated by the court that what the petitioners were requesting was not an existing pension but rather a projected benefit under a system that had been repealed. This was the reason why the court denied this. Without a doubt, there was no violation of a legally protected property right. Estoppel against the state is not permitted.

The petitioners argued that the state should not back out of its pledge to provide pensions after encouraging workers to participate in the 1999 program. They did this by invoking the principle of promissory estoppel.

The Court, however, came to the conclusion that estoppel does not apply in situations where there is an overriding public interest and policy involved. The state’s inability to meet its financial obligations was a solid justification for the withdrawal of the scheme. Finality and the Discipline of the Judicial System

Additionally, the Court reaffirmed that judicial certainty is undermined when there is recurrent litigation on the same subject line. Those decisions that are handed down by the Supreme Court are final and cannot be challenged in a secondary manner. In addition to destroying the notion of finality in law, reopening such situations without first pursuing the constitutional procedure (review or curative petition) will result in administrative pandemonium.

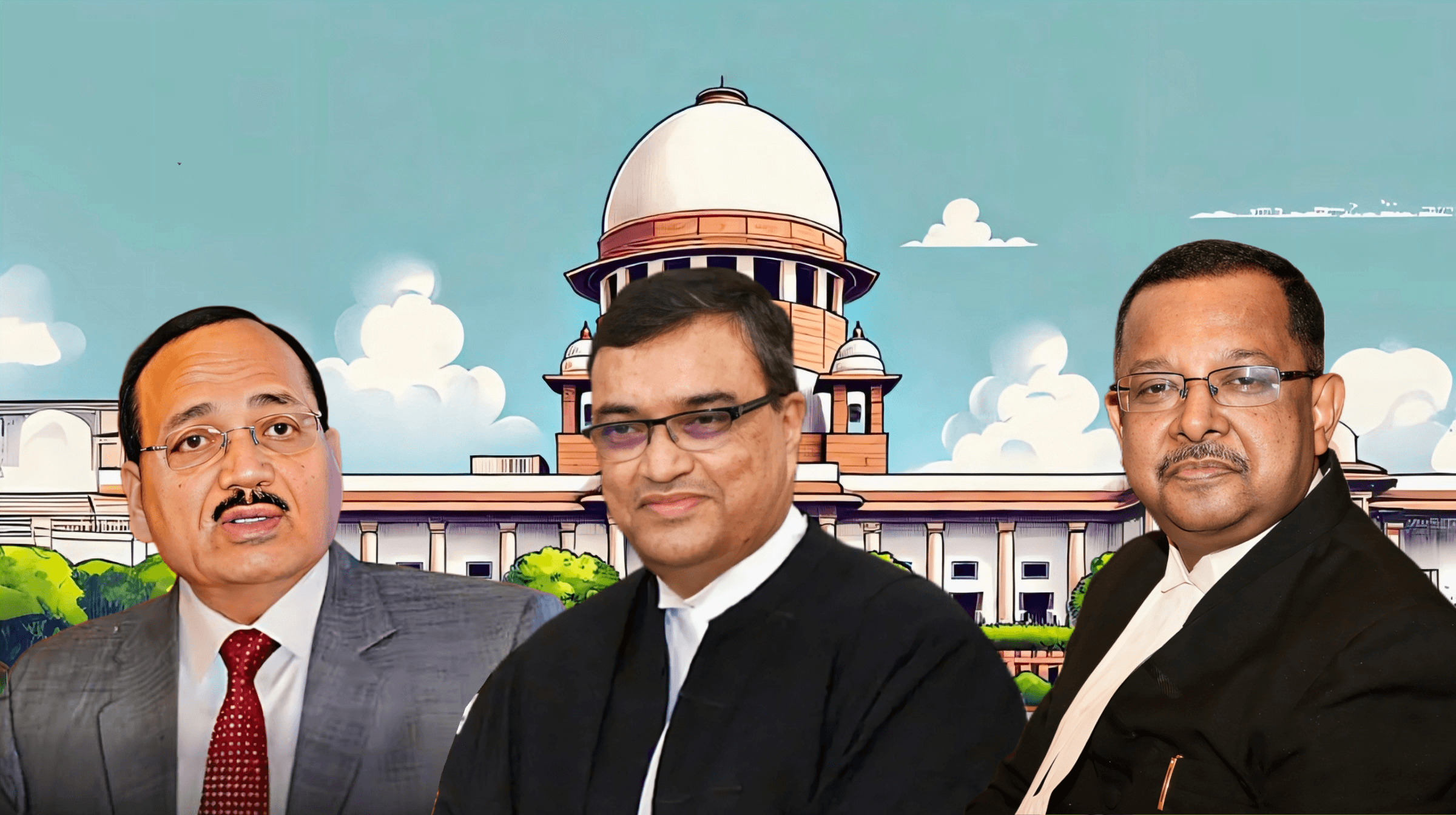

Arguments of the Court Justices Surya Kant, Dipankar Datta, and Ujjal Bhuyan presented a comprehensive reasoning for the dismissal of the case, which included the following: When the former case was being considered, the problem had already been thoroughly discussed and decided upon. The submission of a new writ petition based on the identical facts is not permitted.

Not a single substantive argument could be made to support the contention that the earlier ruling disregarded significant statutes. An appropriate analysis of the scheme’s potential for financial success had been carried out by a High-Level Committee. The class of petitioners had not been excluded in an arbitrary manner; the cut-off date had a clear connection to the goals that were being implemented.

It is not possible for the courts to compel a state to continue funding social programs that are no longer viable.

This ruling reaffirms the sanctity of final judicial decisions and makes it quite clear that Article 32 cannot be utilized to resurrect or re-litigate matters that have already been resolved. Additionally, it reaffirms the state’s authority to remove policy plans, such as pension payments, in the event that there is a concern regarding the possibility of financial sustainability.

The decision highlights a key balance in Indian constitutional law, which is between the expectations of individuals and the expectations of the greater public interest. Despite the fact that the Court acknowledged the difficulties that the retired employees were experiencing, it was adamant in its belief that those difficulties must not be allowed to supersede the law.

This was especially true when the Court determined that the state’s action was legitimate and within its administrative power. Not only did the Supreme Court successfully preserve its own power by doing so, but it also established a clear precedent for how matters of a similar nature should be handled in the time to come.