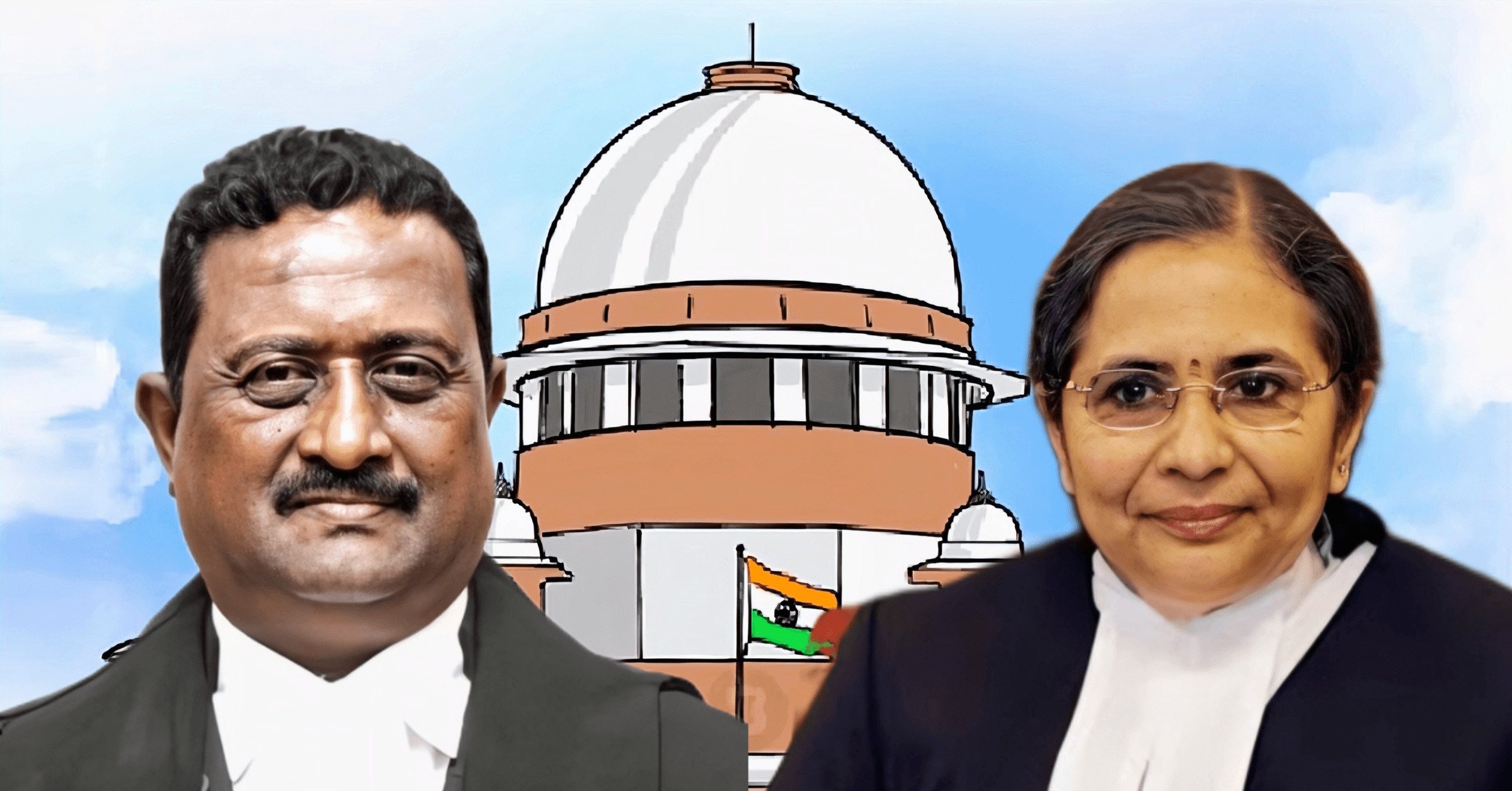

An acquittal of a public worker was overturned by the Supreme Court of India in the case of State of Karnataka vs. Nagesh, Criminal Appeal No. 773 of 2013, which was handed down on April 16, 2025 by Justices Bela M. Trivedi and Prasanna B. Varale. The conviction for receiving a bribe was reinstated.

The case sheds light on the judicial approach to corruption-related offenses, the trustworthiness of evidence, the application of legal presumptions, and the burden of proof in accordance with the Prevention of Corruption Act, which was passed in 1988.

Historical Context of the Case

The lawsuit arises from a demand for bribes that was made in the year 1995. An application had been submitted by the complainant, which sought to make modifications to the mutation entries of agricultural properties.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

When he approached Nagesh, the village accountant of Kadoli, to inquire about the status of his application, Nagesh reportedly requested a payment of two thousand rupees. As a result of the complainant’s declaration that they were unable to pay the total sum, the demand was initially lowered to Rs. 1,500, and then it was reduced to Rs. 500 as an initial payment.

A complaint was filed with the Lokayukta Police because the complainant was hesitant to pay the bribe. The accused was given Rs. 500 that had been contaminated with phenolphthalein powder.

A trap was set up, and the accused was placed within. The accused took the money and stuffed it into the pocket of his jeans after accepting it. Confirmation that his fingers had come into touch with the contaminated notes was obtained through the use of a sodium carbonate solution. An accusation sheet was submitted in accordance with Sections 7 and 13(1)(d) of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, when read in conjunction with Section 13(2).

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Results of the Trial Court

The accused was found guilty by the trial court in 2006 and was given a sentence of harsh imprisonment for a period of one year in accordance with Section 7 and Section 13(1)(d) read with 13(2) of the Political Constitution Act, in addition to penalties.

It was determined by the court that the prosecution had demonstrated without a shadow of a doubt that the defendant had accepted and demanded a bribe. It relied on the testimony of the person who filed the complaint (PW1) and the shadow witness (PW2), as well as the successful trap and documentation evidence, which included the mahazars taken before and after the success of the trap.

High Court’s decision to acquit

In the year 2012, the High Court of Karnataka overturned the conviction that had been handed down by the lower court and exonerated the accused. In the testimony of PW1 and PW2, it was said that there were contradictions about the manner in which the bribe money was handled and the pocket in which it was stored.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In addition, the High Court expressed skepticism over the timing of the complainant’s application as well as the date of the purported demand. It stated that Exhibit P18, which was the second application, was dated after the bribe was reportedly demanded, which rendered the complainant’s story questionable.

Additionally, the High Court expressed its opinion that the prosecution’s case was hampered by inconsistencies of a small nature, such as the discrepancy in which the hand revealed evidence of phenolphthalein. The investigation came to the conclusion that the presumption that is outlined in Section 20 of the P.C. Act could not be applied since there was not enough evidence of demand and acceptance.

The Analysis of the Supreme Court

The rationale of the High Court was called into question by the Supreme Court, which also identified significant flaws in the manner in which the High Court had evaluated the evidence.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The court came to the conclusion that the High Court attached an excessive amount of significance to relatively small inconsistencies and failed to see the overall consistency and dependability of the prosecution’s case.

In the course of giving the ruling, Justice Varale underlined that slight anomalies, such as variances in witness recollection after a gap of 10 years, should not lead to the dismissal of reliable evidence.

In terms of the substantial particulars, the court determined that the evidence provided by the complainant on the demand and acceptance of the bribe was consistent.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The trap method was carried out in the right manner, the tainted currency was retrieved, and chemical testing demonstrated that the accused had handled the bribe money.

Additionally, the court emphasized that the documentary evidence, in particular the previous application Ex. P22 dated 24.01.1995 (which was ignored by the High Court), provided support for the complainant’s account.

It was discovered that the accused’s statement that the money was shoved into his pocket without his will was an afterthought, and the trap witnesses did not provide any evidence to support this claim.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Section 20 of the Public Company Act contains a presumption.

In this particular instance, the applicability of Section 20 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, which was passed in 1988, was one of the most important legal concerns. Unless the accused can provide evidence to the contrary, this rule gives the court the authority to infer that the accused received a bribe.

It was confirmed by the Supreme Court that the burden of proof switches to the accused after the prosecution has demonstrated that demand and acceptance have occurred. The accused did not give a reasonable explanation for the seizure of the bribe money from his possession in this particular instance.

His defense, which said that the money had been stolen from him and held in his pocket without his will, was not supported by evidence and was refuted by the shadow witness.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Memory of the Witnesses and the Delay in the Proceedings

The fact that the trial took place approximately ten years after the trap was put in place was another issue that the court addressed. It was decided that memory gaps are a natural occurrence over such a lengthy period of time and that they should not be used as a reason to dismiss testimony that is otherwise trustworthy. In a fair and impartial manner, the trial judge had taken into account the lengthy delay and had taken a balanced assessment of the evidence.

Injunctions and Final Prescriptions

In spite of the fact that the court was contemplating whether or not the sentence should be lowered owing to the senior age of the offender, it decided not to offer any compassion. As a result of this, it was determined that corruption committed by public personnel is a grave offense that cannot be excused just because enough time has passed.

In accordance with these rules, the Supreme Court confirmed the punishment handed down by the lower court, which was a year of harsh imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 500.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

A decision was made by the Supreme Court to approve the appeal, which resulted in the High Court’s acquittal being overturned and the conviction and sentence being reinstated. The Supreme Court also ordered the respondent-accused to surrender within two weeks.

This particular instance demonstrates how important it is to conduct a thorough and contextual analysis of the evidence in situations involving corruption. The Supreme Court reiterated the idea that slight anomalies in witness testimony, particularly after lengthy delays, should not completely overshadow the overall integrity of the prosecution’s case.

This approach was confirmed by the Supreme Court. Both the stringent interpretation of the Prevention of Corruption Act and the necessity of putting an end to corruption in public sector administration were underlined in this document.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In addition, the ruling reaffirms that once demand and acceptance have been demonstrated, the statutory presumption that is outlined in Section 20 of the P.C. Act becomes an effective instrument in the hands of the prosecution.

It is permissible for the courts to make negative conclusions and punish public officials who are determined to have engaged in corrupt acts, provided that the accused parties do not present a persuasive argument to the contrary.

![Research Assistantship @ Sahibnoor Singh Sindhu, [Remote; Stipend of Rs. 7.5k; Dec 2025 & Jan 2026]: Apply by Nov 14, 2025!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_s0k4u6s0k4u6s0k4-768x707.png)

![Karanjawala & Co Hiring Freshers for Legal Counsel [Immediate Joining; Full Time Position in Delhi]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_52f8mg52f8mg52f8-768x711.png)