India’s Suspension of Indus Waters Treaty: Legal Ramifications Under International Law and VCLT Article 62

In the beginning

The announcement made by India in April 2025 that it would be suspending the Indus Waters Treaty has sent shockwaves to spread throughout the region and has brought up basic problems regarding the rule of law in the context of international water sharing. Even throughout times of conflict and crisis, this pact continued to serve as an example for India and Pakistan to work together in the management of water resources for more than six decades.

In the aftermath of a tragic attack in Kashmir, New Delhi asserted that there was a pressing security rationale for declaring the pact to be “in abeyance.” The unilateral suspension of a treaty, on the other hand, is fraught with significant legal concerns according to public international law.

Within the scope of this article, the legal framework that governs the suspension of treaties is investigated, with a particular emphasis placed on Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. We investigate whether India’s action can be justified as a response to a fundamental shift in circumstances, what countermeasures are permitted by the treaty arrangement, and what potential hazards may lie ahead for both parties.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

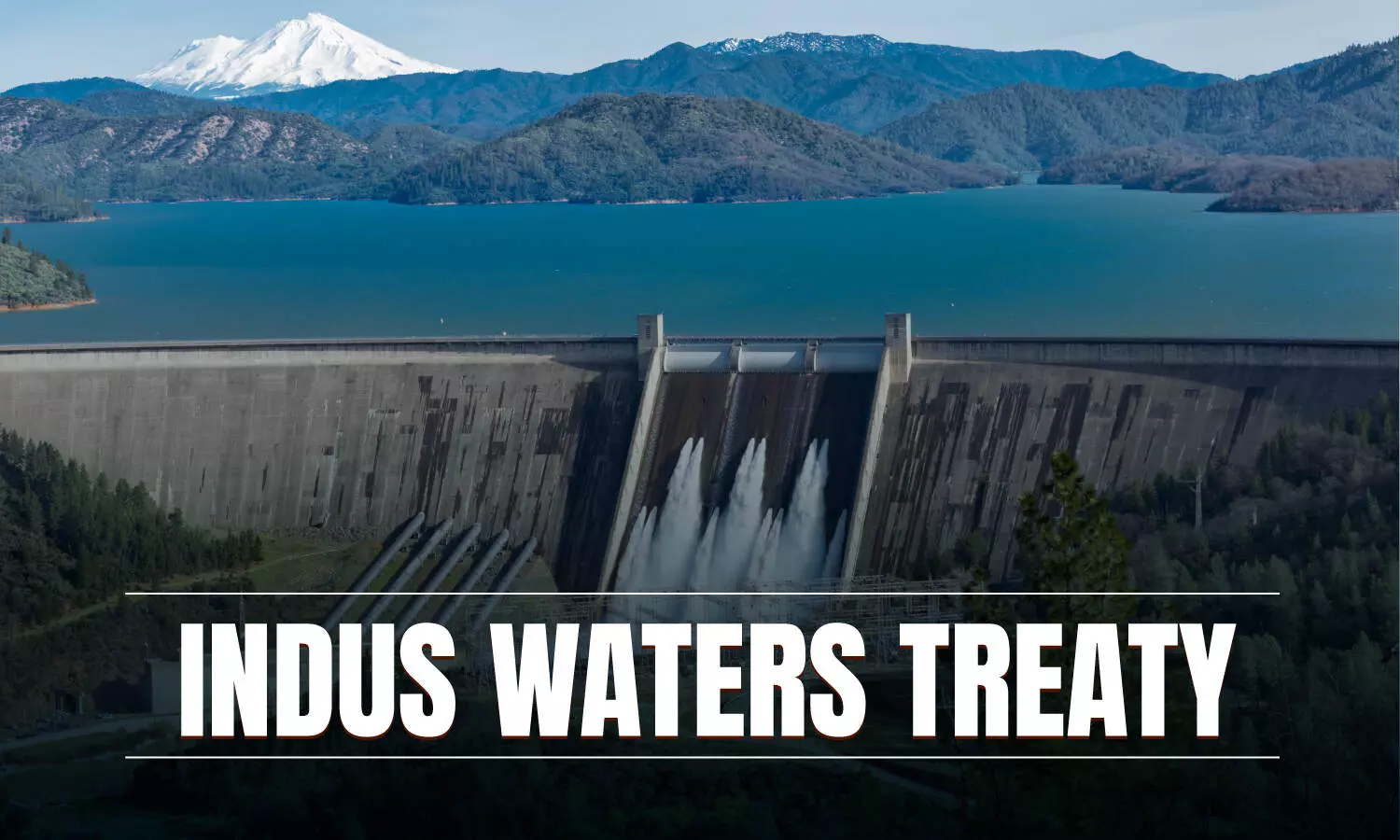

Taking a Quick Look at the Indus Waters Treaty

In 1960, the World Bank was responsible for negotiating and mediating the Indus Waters Treaty, which resulted in the distribution of the six rivers that make up the Indus basin between India and Pakistan.

It gives India complete authority over the rivers in the east, including the Ravi, the Beas, and the Sutlej, while it gives Pakistan unrestricted access to the rivers in the west, including the Indus, the Jhelum, and the Chenab, with the conditions that they are subject to limited non-consumptive activities and minimal flows.

Over the course of several decades, both nations have depended on the procedures provided by the treaty for the purpose of data exchange and dispute resolution. They have utilized the Permanent Indus Commission to monitor the day-to-day implementation of the pact, and they have referred any problems that were either technical or legal to arbitration or other international courts.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

As a result of the treaty’s ability to withstand several crises, it became an exceptional example of diplomatic achievement in a partnership that was prone to instability.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

Arguments in Support of Suspension

On April 23, 2025, the Cabinet Committee on Security of India made the announcement that it would put the pact on hold until Pakistan “credibly and irrevocably” stopped providing any support for terrorist activities that occurred across the border. According to New Delhi, Pakistani-based militant groups were responsible for the savage attack that took place in the Pahalgam district of Kashmir, which prompted this announcement.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The suspension was accompanied by India’s decision to stop the discharge of Chenab River flows and to cleanse reservoirs at important dams during the off-season. These actions resulted in a significant reduction in the amount of water that was available to Pakistan downstream.

Through the establishment of a connection between the execution of treaties and concerns regarding national security, India presented its move as a necessary response to Pakistan’s purported breach of good faith over counterterrorism.

Revocation of the Treaty The Vienna Convention stipulates that

Treaty suspension is primarily understood through the lens of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), which provides the basic framework involved. A significant portion of the VCLT’s text is reflective of customary international law, notwithstanding the fact that India and Pakistan are not parties to the VCLT.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

A party may cite a “fundamental change of circumstances” (rebus sic stantibus) as a basis for terminating or withdrawing from a treaty, as stated in Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT).

In order to be eligible, the modification must not have been anticipated at the time of the treaty’s signing, it must be decisive in the duties described in the treaty, and it must not be the result of a party’s own violation of its commitments.

When it comes to Indus Waters, applying Article 62

Connecting the execution of the treaty to a more comprehensive security environment is the foundation upon which India’s claim of a fundamental transformation is built. However, the language of the Indus Waters Treaty does not include either the fight against terrorism or the protection of national security.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It is primarily concerned with the distribution of water, the exchange of data, and the collaboration of technical experts. The argument that Pakistan’s alleged assistance for terrorism substantially affects the circumstances that underpin a water-sharing treaty is an example of Article 62 being stretched beyond its conventional meaning.

The question of whether a security threat that is unrelated to water flows or treaty processes can have the ability to justify suspending obligations that are not related is an important one. According to the historical practice, the rebus sic stantibus doctrine is reserved for changes that are so significant that they challenge the entire premise of cooperation on which a treaty was established.

For example, rising water scarcity or enormous hydrological shifts are examples of such changes. However, geopolitical disagreements over terrorism are not appropriate for this doctrine.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Proportionality and Countermeasures are Included

It is recognized by international law that countermeasures are a permissible response to a previous unlawful act, even if the fundamental change cannot warrant suspension. According to the Articles on State Responsibility published by the International Law Commission, a state that has been harmed by the breach of another state has the ability to take reasonable countermeasures in order to compel compliance, provided that these countermeasures are reversible and do not violate non-derogable duties.

It is possible for India to argue that Pakistan’s failure to suppress terrorism constitutes a wrongdoing and that the treaty being held in abeyance is a countermeasure that can be reversed. Nevertheless, countermeasures must have the objective of restoring the legal order, and they must not involve causing irreparable injury to essential interests, such as depriving Pakistan’s fields of water during the planting season without doing so.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In light of these conditions, India’s conduct will be subjected to a great deal of scrutiny about its proportionality and its ability to be reversed.

Improper Behavior and the Responsibility of the State

Pakistan, on the other hand, may argue that India’s unilateral suspension itself constitutes a violation of an international legal requirement or obligation. It can be argued that India has violated the treaty’s clear stipulations for cooperation and minimum flows by putting an end to the sharing of data and making changes to flow regimes.

In accordance with the principle of state responsibility, unjust acts cause a claim for reparations to be filed on an international level. Pakistan might either file a claim with an international court or seek remedies through a dispute resolution system that was established by the treaty.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

They both have the ability to do so. Invoking security concerns would then put India in conflict with the “necessity” defense, which is outlined in the Articles of the International Law Commission.

This defense demands that the act in question was the only option to protect an essential interest from a grave and imminent threat. There will be a critical legal battleground between the question of whether or not national security is sufficient to overcome obligatory treaty obligations.

The World Bank’s Function in its Role

Signatory and mediator of the Indus Waters Treaty is the World Bank, which is designated as such in the treaty. The legality of the treaty is supported by the Bank’s perceived impartiality, despite the fact that its powers are restricted to assisting discussions and funding commissions of experts with limited authority.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The fact that India did not inform the World Bank of its suspension diminishes the function that the institution plays and may harm the larger system of water diplomacy that it represents. Any potential legal challenge may be made even more difficult if the Bank were to refuse to provide funds or assistance for tribunal procedures in the event that future attempts at arbitration are made.

Influence on the Stability of the Region

The distribution of water is a crucial resource in South Asia; if it were to be altered unilaterally, it would put downstream Pakistan at risk of experiencing devastating humanitarian and agricultural disasters.

Reduced flows pose a threat to the generation of hydropower, as well as to the livelihoods of rural residents. Within Pakistan, domestic demonstrations and political pressures have the potential to intensify military tensions, with both sides considering the other’s control of water as a means of gaining existential power.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It is possible that the violation of a long-standing convention might also establish a perilous precedent on a global scale, which would encourage riparian parties in other regions to reconsider multilateral water agreements in the event that geopolitical conflicts arise. It is possible that the ripple effects on international water law could cause governments to become more confrontational in their strategies, which will in turn diminish faith in treaty-based dispute settlement.

Possible Future Ways to Find a Resolution

There are incentives for both countries to return to the bargaining table in order to prevent a full-scale conflict from occurring. On the condition that Pakistan takes verifiable counterterrorism initiatives, possibly under the supervision of a neutral third party, India may agree to restore treaty operations with a time limit attached to them.

On the other hand, Pakistan can try to obtain firm guarantees of water security that are supported by impartial international monitors. The Permanent Indus Commission should be resurrected with increased authority and transparency in order to assist in the process of reestablishing trust.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The viability of the pact can only be restored by the implementation of a consensual solution that takes into account both the sharing of water and concerns regarding security.

The Indus Waters Treaty was suspended by India on the grounds that there had been a fundamental change in circumstances. This action offers a significant challenge to the principles of international law. Article 62 of the VCLT and the state responsibility regime of the ILC both offer established avenues for justification and challenge from the perspective of the legal system.

Nevertheless, neither the idea of rebus sic stantibus nor countermeasure law provides a legal cloak that is infallible for the purpose of unilaterally abstaining from treaty obligations. By taking this action, there is a possibility of violating legally binding agreements, prompting demands for damages, and weakening a model of water cooperation that is nearly ubiquitous.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

During this time of growing tensions in the region, the parties involved are required to handle both their legal commitments and the diplomatic imperatives that they face. They will be able to determine whether or not the treaty will survive this crisis based on their ability to combine respect for the rule of law with the immediate requirements of security and humanitarian aid.