Introduction

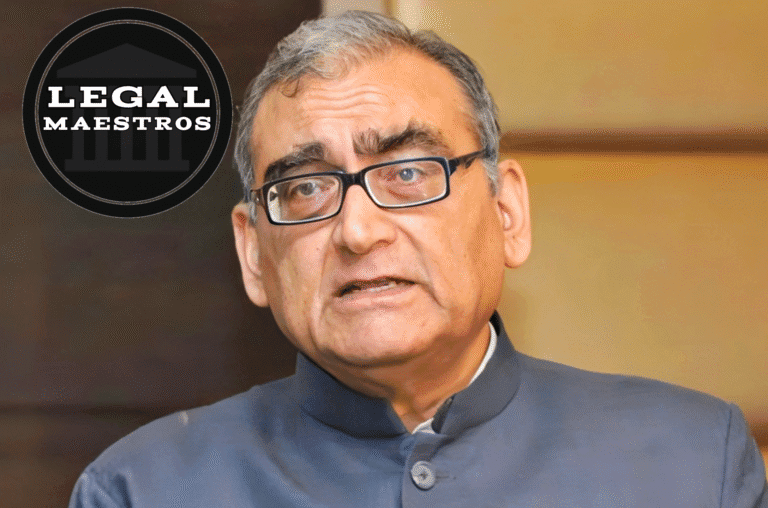

Chief Justice Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai’s tenure as the 52nd Chief Justice of India lasted a bit more than six months- from 14 May 2025 to 23rd November 2025. Although not so long his period in the office of CJI generated intense debate both online and offline. As the Master of Roaster, head of Collegium, and a constitutional judge presiding over sensitive litigation, CJI Gavai left behind a short but contested legacy marked by doctrinal shifts, administrative assertiveness, and clear opacity in a lot of procedures.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

This article examines: –

- The key judgments delivered under his leadership,

- His exercise of roster powers

- His role within the Collegium – including allegations of nepotism

- The broader constitutional significance of his institutional choices.

While acknowledging some positive outcomes such as reduction of vacancies and better co-operation between the Judiciary and executive this analysis will discuss the structural changes which CJI Gavai’s tenure left behind, Judicial Independence, doctrinal stability, and the perception among common citizens of judiciary.

- Key Judgments Delivered During His Tenure

- The Vanashakti Recall: Expanding the Scope of Judicial Recall

One of the most Consequential judgments associated with this short tenure of CJI Gavai was the recall of the Vanshakti judgment which was delivered in May 2025. This judgment of Vanashakti v. Union of India, had categorically barred grants of ex post facto environmental clearances for industrial and infrastructure projects. This recall judgment was delivered by a 3 Judge Bench which was headed by CJI Gavai. The Majority invoked public interest and prevention of a greater loss to industry as a reason behind the recalling and changing of the earlier judgment. The judgment suggested that environmental compliance, while important, should be balanced with national developmental priorities which clearly indicates where this was coming from.

This marked a significant shift from earlier jurisprudence emphasising precautionary principles, polluter-pays and sustainable development under Article 21. Gavai’s majority adopted a whole different approach: prioritising economic continuity over strict environmental discipline. The dissenting view argued that the majority disregarded settled principles and diluted the Court’s commitment to environmental protection as a key point to the right to life. Justice Bhuyan who held the minority view argued that the recall overlooked the fundamentals of environmental jurisprudence and was a step in clear retrogression.

Moreover, this recall raised various concerns regarding the power of the Court to recall its own judgment which is quite narrow and is applied in the cases of patent errors, fraud, etc. The recall overlooked these settled principles of law and environmental jurisprudence and this also undermined the principle of Stare Decisis.

- The Presidential Reference on Constitutional Powers of Governors

A second major development under CJI Gavai was the Court’s handling of the Presidential Reference under Article 143, concerning the constitutional boundaries of the powers of the Governor and to an extent the President in assent to Bills, withholding assent, returning bills, and time-limits for such actions.

The Court’s advisory opinion though technically non-binding has significant precedential influence. Delivered by a five-judge Constitution Bench headed by CJI Gavai, the opinion attempted to clarify long-standing ambiguities in India’s federal structure.

Three aspects stand out:

- The Court reaffirmed that gubernatorial powers must be exercised on aid and advice, but allowed a limited window for discretionary delay in constitutional impropriety cases but event in that the court hasn’t clarified what amounts to what.

- The Court held that the Governor cannot indefinitely withhold assent, but provided no explicit time-limit leaving the doctrine vague.

- The Court did not address in detail how political misuse of gubernatorial office can be prevented and essentially left the power on discretion of the governor which gives centre a lot of discretion in state bills.

The Bench constituting CJI Gavai essentially made Supreme Court a de facto power broker between the State and Centre Dispute on bill’s assent, even in doing so they have not provided clear guidelines.

Further, it needs to be highlighted that CJI Gavai described the judgment as relying on a “swadeshi interpretation,” avoiding reliance on any foreign precedents. While the slogan of indigenous jurisprudence may appeal, in practice of such slogans the court will essentially avoid what other democracies have adapted in similar constitutional crisis of balancing federalism. It can be clearly said that without fixed criteria or timelines, future governors and legislatures will face uncertain judgments from the Supreme Court which will further undermine the doctrine of Stare decisis as each dispute will invite fresh interpretation without a stable jurisprudential or doctrinal support.

- Electoral Roll Revision Litigation

CJI Gavai also presided over interim orders related to the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar. Petitioners were challenging the mass deletion of names from the rolls without adequate notice. The Court permitted SIR to continue but directed them to practise safeguards. This was balanced approach but the Court failed to address the issue meaningfully by addressing the core constitutional issues of mass disenfranchisement an issue which is highly connected with Article 14, Article 21 and the Basic Structure Doctrine. The restrain exercised by court is a clear case of Judicial minimalism.

III. Use of Master of the Roster Powers

- Administrative Assertiveness and Bench Composition

CJI Gavai adopted a visibly assertive approach in his job, two distinctive patterns emerged when he was the Master of Roaster and did the allocation of cases and composition of benches:

- The creation of special three-judge benches to revisit recent judgments as done in Vanashakti and Re: City hounded by Strays, Kids pay price.

- Frequent re-listing of matters for “recall” or “reconsideration,” often at short notice and executive friendly reconsideration of the recalled judgments as highlighted again in the Vanshakti, Bihar Electoral roll Judgment and Street Dog issue of Delhi NCR.

While no formal rules prohibit such actions, they intensify concerns about the opacity of roster powers. Scholar have long argued that unchecked power of the roaster to the CJI or any single entity leads to structural asymmetry. CJI decides the composition the Benches and through that control the outcomes of Judgments.

This concern although existed throughout the recent history of Indian Legal System, it crystallised during the tenure of CJI Gavai; allocation of benches appeared less neutral work rather they seemed more of a planned strategic realignment of Benches to generate preferred outcomes. Even though no rule was broken but the blanket appearance of outcome-oriented benches undermines the legitimacy of the judiciary.

B. Transfers and the Executive-Judiciary Relationship

A notable administrative development involved the transfer of a High Court judge—Justice Atul Sreedharan. The Collegium publicly acknowledged revisiting the transfer proposal following the Union Government’s objection.

The origin of the mandate to transfer judges of High Court from one to another was done to spread legal talent where it was scarce. As time passed, these transfers were rationalized under the guise of “National Integration” or “Better Administration”. Yet, the reality becomes starker day by day that the mechanism designed to spread talent is being used by the executive to flex its dominance.

IV. Collegium Functioning and Concerns of Nepotism

A. Accelerated Appointments and Reduction of Vacancies

A positive administration outcome during the tenure of CJI Gavai was the smoother and faster appointment of High Court Judges, various high court’s vacancies fell short, government acceptance rate was quite high. This indicated a better co-operation between the judiciary and the executive.

B. Allegations of Nepotism: The Wakode Controversy

Yet controversies mounted when the Collegium recommended Raj Damodar Wakode for elevation to the Bombay High Court. It was highly reported Wakode is nephew of CJI Gavai. Although, the CJI never himself commented on the issue the silence grew louder and clearly indicated that the allegations were indeed true and this event raised several transparency concerns on both the collegium system and CJI.

Indian judicial ethics emphasise both actual fairness and the appearance of the fairness among the citizens. In an already opaque system i.e. Collegium appointing one’s own nephew gives a very negative impression. Several media commentaries flagged other names recommended who had past professional association with the CJI, this further intensified the allegation of patronage on the CJI.

C. Collegium Transparency: Missed Opportunities

Despite marginal improvements, the Collegium under CJI Gavai did not publish detailed reasons for its selections or rejections. The retention of dissenting notes as confidential including one authored by Justice B.V. Nagarathna in another recommendation, reaffirmed longstanding criticism that the Collegium lacks democratic legitimacy and transparency it was an opaque system which over time is becoming more and more like a closed room cult.

Comparative jurisdictions e.g., UK, South Africa publish extensive grounds for judicial appointments. India’s continued reliance on unwritten conventions and closed deliberations makes the system uniquely vulnerable to allegations of favouritism.

V. Broader Constitutional Outcomes

A. Doctrinal Stability vs. Pragmatic Flexibility

One pattern which one can clearly observe from the tenure of CJI Gavai is shift from Doctrinal rigidity to pragmatic approaches whether in balancing Dog rights, Environmental issues or election issues. While on paper it might look good but in reality, there was clear shift away from established doctrines which clearly undermines the doctrine of Stare Decisis excessive flexibility undermines constitutional safeguards.

The Vanashakti recall weakened environmental enforcement. The Article 143 advisory opinion left open broad discretionary spaces for constitutional functionaries. The interim orders in electoral matters favoured administrative continuity over rights-based scrutiny. The Dog rights matters was not solved rather created more issues and protests.

Thus, the jurisprudential and constitutional legacy of this tenure of CJI Gavai is a turn toward administrative pragmatism, sometimes even at the expense of rights-based doctrine, predictable legal standards and constitutional safeguards of both environment and citizens.

B. Institutional Legitimacy and Public Trust

Three factors combined to cast a shadow over institutional legitimacy:

- Frequent recalls and reconsiderations, creating an impression of instability in constitutional adjudication.

- Opaque roster decisions, perceived as outcome-shaping rather than neutral case-listing.

- Clear case of familial appointments, which harmed public confidence even if procedural steps were followed, this harms the public image of judicial system.

Institutional legitimacy depends not only upon the constitutional correctness but also on the confidence of the public which adopted that very constitution. In a democracy, the judiciary’s strength is derived from public confidence which once eroded is difficult to restore. The strong rhetorical claim of “Swadeshi Jurisprudence” while seems great create a greater harm to the already established principles of the democracy and its constitution.

VI. Concluding Assessment

CJI B.R. Gavai’s tenure must be understood as a juxtaposition of administrative efficiency and institutional controversy. On the one hand, he accelerated judicial appointments, reduced High Court vacancies and maintained a steady flow of constitutionally significant litigation. On the other, his tenure raised structural concerns: the robust use of roster power and recall jurisdiction stretched procedural standards; collegium controversies particularly regarding familial rise revived the debate on nepotism; and the environmental jurisprudence and the presidential reference reassure pragmatism but provoke questions about doctrinal coherence.

In the end, CJI Gavai’s legacy is one of contested direction combined with assertive leadership. His brief tenure will be examined as an example of how high judicial office, despite its brief tenure, can have enduring institutional and doctrinal impacts.