Karnataka’s Argument Before the Supreme Court

Karnataka government has taken the case to the Supreme Court and one of the more important legal questions that they have focused attention on is whether the Enforcement Directorate (ED) is supposed to give written reasons for arrest in every previous and upcoming arrest case or simply in the arrests that were conducted after the day of the Supreme Court decision in Pankaj Bansal v. Union of India?

The state government has stated that the provision that the ED roundrip_cr后 eliminating that cases in which the reasons why an arrest was made (a matter that is required by law to be presented in written form) were not provided by the ED, should be considered as applying going forward and not in the past. The plea made by Karnataka is one of the many pleas to safeguard previous ED proceedings under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

Background of the case: Pankaj Bansal’s arrest

Pankaj Bansal, the developer and promoter of M3M Group was arrested by the ED in a money laundering case. He disputed his arrest citing that the ED did not abide by legal procedures that were mandatory. Among the major reasons why he challenged it was because the ED failed to provide him with the written grounds for arrest hence infringing on his fundamental rights under article 21 of the Constitution.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In a first of its kind, the Supreme Court ruled that although giving written reasons at the time of arrest is not a formality but a safeguard to avoid arrests against deserving persons, giving written reasons is required to allow the arrested person to avail his/her legal rights effectively like seeking bail or a challenge to the arrest.

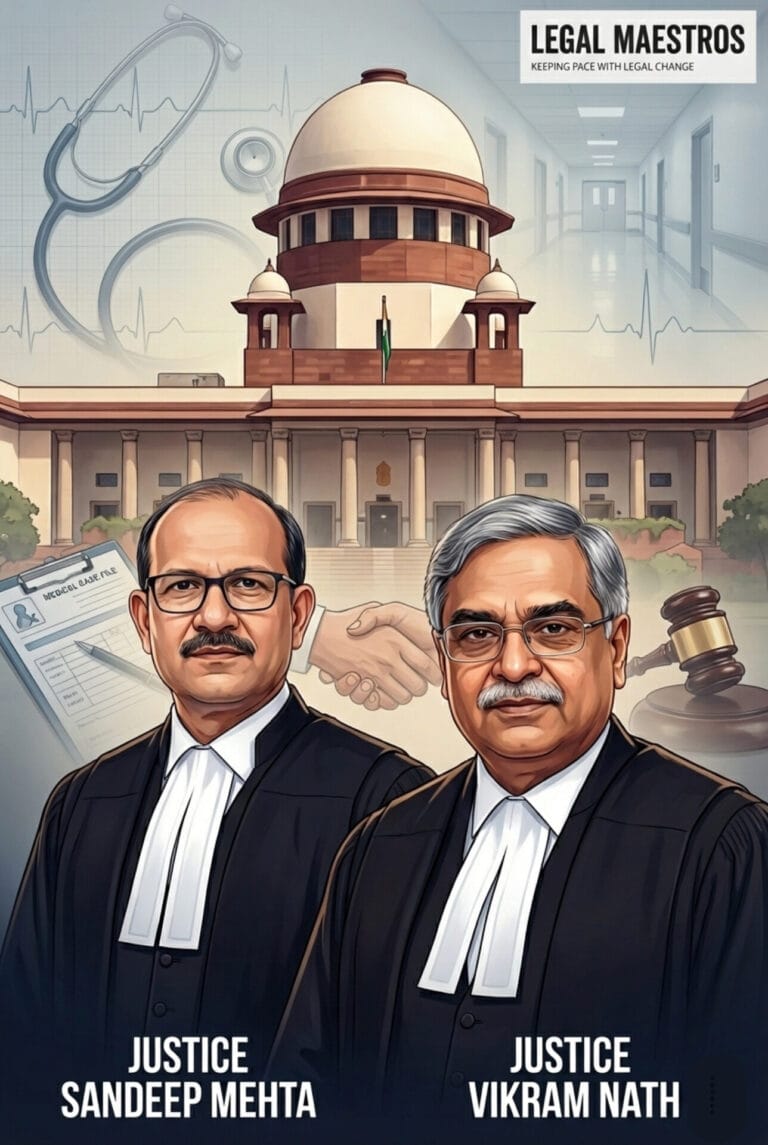

The historic ruling of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court in its ruling pointed out that the liberty of an individual cannot be arbitrarily derogated. The bench observed that rationales for arrest have to be presented in writing and that it is not enough to convey the same orally because it cannot fulfill constitutional requirements. In laying emphasis on the right to be aware of the reason for arrest, the ruling highlighted the fact that the right is implied in Article 22(1) of the Constitution and supported by Sections 19 and 45 of the PMLA.

The Court explained that the ED, just like other law enforcement institutions, does not enjoy exemption from constitutional considerations. A warrantless arrest just deprives a person of his right to procedural fairness and natural justice since the written reasons for the arrest are not revealed. The Court then quashed the arrest of Bansal therefore.

Karnataka’s Stand: Prospective or Retrospective?

The legal tussle now centers on the scope of the Supreme Court’s ruling. Karnataka contends that the requirement to supply written grounds for arrest should apply only to arrests made after the date of the judgment. According to the state, applying this requirement retrospectively could jeopardize numerous past cases and investigations conducted under PMLA.

The government’s counsel argues that interpreting the ruling as prospective avoids creating chaos in the legal system. It asserts that many arrests were made based on existing understanding of the law and prevailing ED procedures, which were not considered invalid at the time. Retrospective application, they argue, would unfairly penalize officers and undermine legal proceedings that were, until now, thought to be valid.

The problem of applying justice retrospectively by using past judicial rulings is referred to as the Legal Debate.

Among the fundamental questions of the law before the court, a question that is essential to submit before the court is whether its interpretation of the constitution is to have retroactive or prospective effect. Even the constitutional jurisprudence of India presumes retrospective application except when the Court makes clear that it hopes that its judgment should give prospective application only.

The Karnataka government has sought explicit clarification from the Supreme Court. They are relying on the principle that courts have the power to limit the effect of their decisions when a prospective application is necessary to preserve the rule of law or avoid disruption of settled legal procedures.

There is no precedent for this argument. When applied in previous scenarios like Golaknath v. I.R. Coelho and the State of Punjab. The Supreme Court in the State of Tamil Nadu touched upon the doctrine of prospective overruling particularly where the court was concerned with constitutional interpretation and actual effects of such interpretation on past acts.

Implications for ED and Law Enforcement

If the Court agrees with Karnataka’s interpretation, the ED’s obligation to furnish written arrest reasons will only apply going forward. This will provide legal cover for all past arrests made without written communication of the grounds. However, it will also mean that individuals previously arrested under questionable procedures may not be able to seek relief based on the Pankaj Bansal ruling.

On the other hand, if the Court holds that the ruling has retrospective effect, it could open the floodgates to litigation against the ED. Many arrests and detentions under PMLA may be challenged as unconstitutional, leading to potential release of the accused persons, delays in trial, and overall weakening of ongoing enforcement actions.

The ED is one of the central agencies and it crosses all states. Thus, it is important to shed some light on this problem, which is not only significant in the case of the state of Karnataka but also the rest of the states and the Union government.

Failure to protect fundamental rights

Legal specialists and civil rights activists believe that the retrospective implementation of the judgment should be performed in order to enforce the rule of law. They argue that where an underlying fundamental right that happens to be under Article 21 or Article 22 has been infringed, there is a violation of Article 22.the individual affected must be given relief regardless of when the arrest occurred.

The principle of fairness cannot be tied only to a date, they say. If a constitutional right was denied in the past, it should be corrected, not ignored. This argument places individual liberty above administrative convenience.

There will be a fine balance that the Supreme Court must strike between the protection of constitutional rights and the stability of the law. Its decision will probably form a model for the interpretation of basic procedural assurances and their application to other cases of this sort.

The play of Article 21 and Article 22

The ruling in the Pankaj Bansal case was a reference to the right provided in Article 21 which guarantees that no human being should be denied the right to life or personal liberty except by a process established by law. It also brought out Article 22 (1) which grants every arrested individual the right to access the reasons for their arrest and the right to consult a legal practitioner.

The reiteration of such rights by the Court is an important step towards bring acceptance of accountability and transparency while arresting a person under special laws such as PMLA. It is by centering itself on the constitutional foundation, that the Court aims to curb the arbitrary use of power by investigative agencies.

Awaiting clarification and Broader Consequences

As the Supreme Court now considers Karnataka’s request for prospective limitations, the final verdict will not only determine the fate of Pankaj Bansal’s arrest but also influence hundreds of ongoing and past cases under PMLA. It will define whether constitutional rights can be enforced retrospectively in the context of arrests made without written reasons.

The ruling will further act as a guiding factor for law enforcement authorities on the minimum procedures that they should abide by when making arrests according to PMLA and other such statutes.

The argument about whether the Pankaj Bansal judgment will apply retrospectively or prospectively is not a mere technicality. It brings fundamental issues of freedom, legal justice, and the extent to which the U.S. Constitution applies to the past. In anticipation of a decision by the Supreme Court, it is already apparent what the consequence is, which could significantly alter the legal landscape for white-collar crime investigations in India.

1 thought on “Pankaj Bansal Verdict: Karnataka Contends ED’s Obligation to Supply Written Arrest Reasons Applies Only Prospectively in Supreme Court”