The Supreme Court of India made a very important decision in Suo Motu Writ Petition (Civil) No. 7 of 2024 on April 22, 2025. The case was not started by a plaintiff, but by an email from Shri B.B. Pathak, a retired District Judge from Gujarat.

He brought up a shocking problem: a lot of money that was supposed to be paid out as compensation under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 and the Workmen’s Compensation Act, 1923 was still sitting in different Motor Accident Claims Tribunals (MAC Tribunals) and Labour Courts all throughout India.

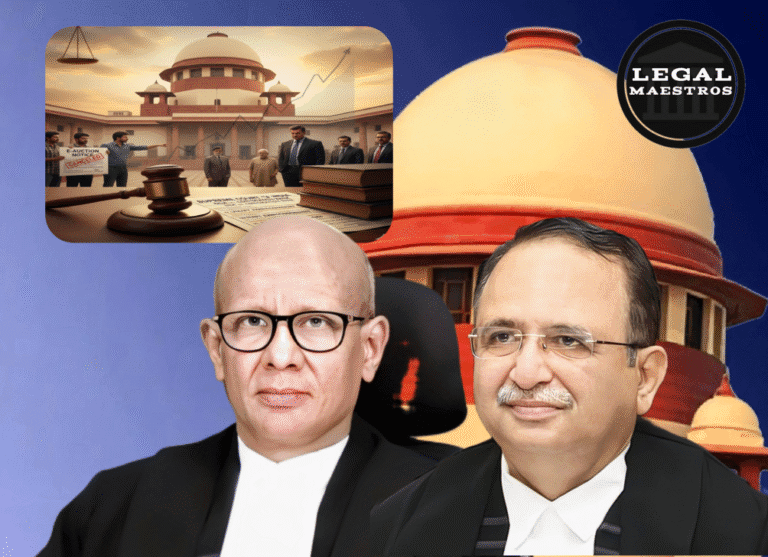

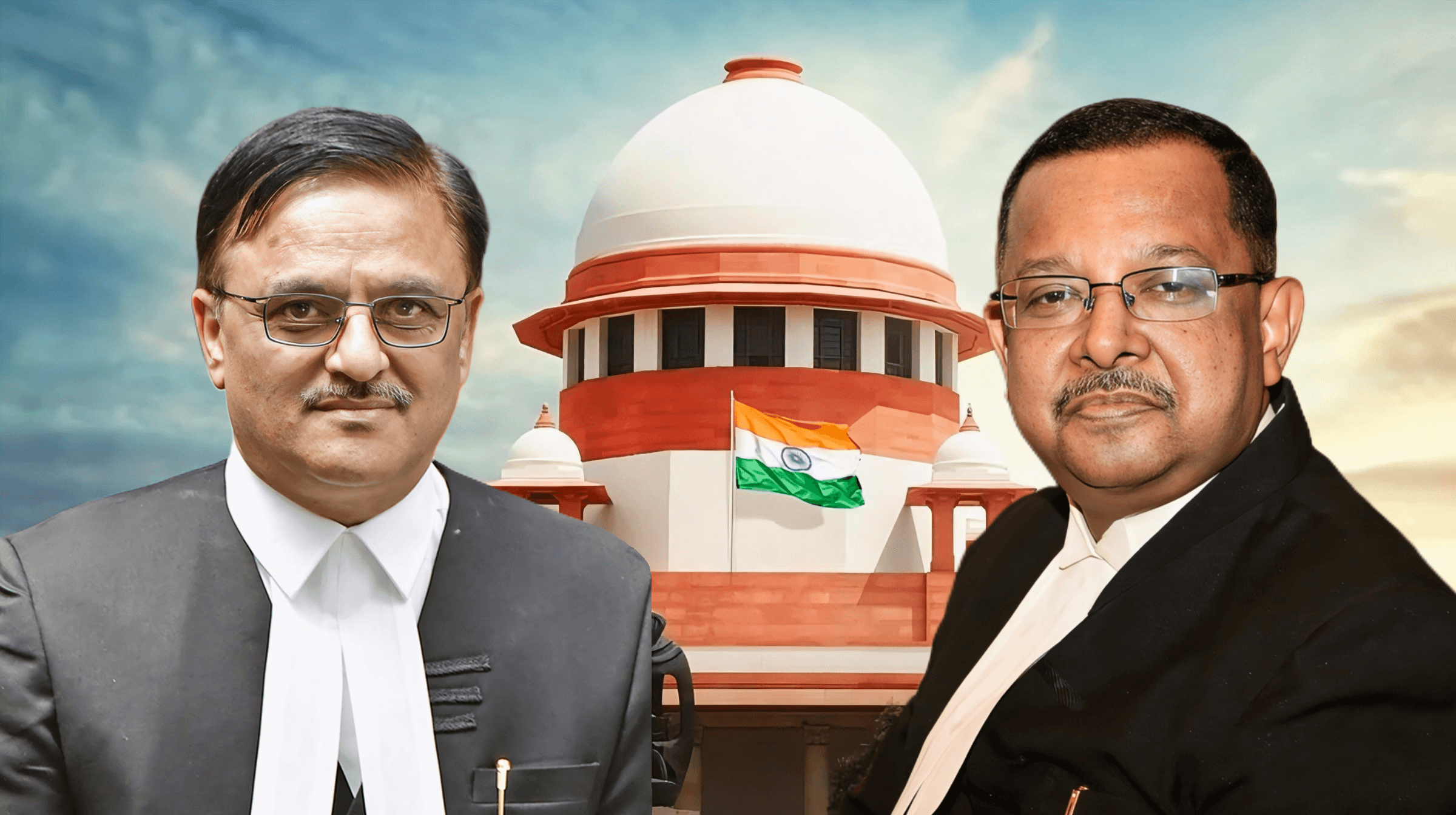

The Chief Justice of India acted quickly and ordered the registration of a suo motu petition, which led to a judicial review of this systematic flaw in the delivery of justice. Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan were on the Court bench.

They not only looked into the matter, but they also gave detailed instructions on how to close the gap between awards and actual payment of damages.

Facts and important events

This was a suo motu case and the State of Gujarat and the Registrar General of the Gujarat High Court were the first individuals who responded to it.

The Court subsequently sent out the notifications to the High Courts of Allahabad, Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi and Madras. Ms. Meenakshi Arora, a well known lawyer was made amicus curiae in an attempt to enable the bench to understand and clarify the issue.

Affidavits and answers submitted to the Court showed that the amounts of unclaimed compensation were quite high.

For instance, Gujarat had ₹288 crore that no one claimed, while Bombay had an even bigger amount—almost ₹459 crore. Other High Courts sent in similar information, showing that there is a countrywide issue in paying victims of car and occupational accidents.

Looked into the legal provisions

This sentence was mostly concerned with Section 166 and 176 of Motor Vehicles Act, 1988. Section 166 gives MAC Tribunals the legal authority to provide money to anybody who ask for it.

It enables those who were hurt, owners of damaged property, legal heirs of dead victims, or even agents with the right to bring claims for compensation.

Section 176 gives State Governments the right to make regulations for the procedural parts of compensation claims, such as the format of applications, what information must be included, and how investigations should be conducted.

The Court was worried that many States had not used this authority properly, which caused problems and discrepancies in the compensation procedure.

The Court also referred to the Workmen Compensation Act of 1923 that lays down guidelines on compensation of injured or killed employees on the job. The same procedural problems were present here, which shows that changes are needed.

Important Issues and Concerns of the Court

The main problem that was found was that even when the courts decided on compensation claims, the money was not going to the correct people.

The causes were different: missing or incomplete bank information, inefficient procedures, the courts not following up, and the fact that there were no consistent regulations among States.

The Supreme Court said that this was not simply a mistake in administration; it was a failure of justice. The individuals that these laws were meant to help—usually accident victims and their families—were not able to get the help they were legally entitled to. The Court made it clear that the situation was quite troubling.

The Supreme Court’s orders

The Supreme Court gave a set of thorough and enforceable instructions that encompass the whole life of a compensation claim in response to this sad truth.

Until the State Governments make explicit regulations concerning how to do things under Section 176, these instructions apply to MAC Tribunals and Labour Courts all throughout the nation. They consist of:

When claiming for compensation, claimants must include all of their personal information, such as their Aadhar number, PAN number, bank account number, and contact information.

However, tribunals are not in a position to reject petitions that do not provide such details; they must rather inform claimants to provide them with the required details as quickly as possible.

The MAC Tribunals should ensure that the verified bank accounts of claimants receive the appropriate sum of money. If the bank information is out of current, new ones must be gathered before the money is sent out.

When courts require the deposit of compensation payments, they must be put into fixed deposits with nationalized banks that automatically renew until the money is taken out.

Consent awards or settlements must contain all of the bank account information, and disbursal orders must be written in a way that makes this clear.

Judges on the tribunal must check if they own the bank account by looking at documentation such bank certificates or canceled checks.

To make sure that these standards are followed in the same way everywhere, High Courts must make procedural rules or issue practice instructions that are in keeping with them.

The e-Court initiative needs to create a dashboard, with help from State IT agencies, to keep track of deposits and withdrawals across all courts and tribunals.

District and Taluka Legal Services Authorities, with the help of para-legal volunteers and local government workers, must aggressively find and tell claimants whose money has not been claimed.

By July 30, 2025, all High Courts must report on their compliance and send in complete reports showing how much money is still owed.

The Judgment’s Wider Importance

Interesting is the involvement of the Supreme Court whose role has since expanded not just to decide cases, but to ensure that the rights within the law are being observed. This ruling confirms the position that justice is not just supposed to be worked, but must be seen into, as well as felt by the citizens.

This ruling demonstrates that the Court is veering on the side of the greater good especially to those who suffer at the hands of offenders, who are usually poor and cannot afford the effects of going to court.

This action also shows how important it is for state governments to do their job of creating rules. The Court has avoided bureaucratic delays by giving High Courts the competence to make orders in the interim.

The fact that legal services authorities, para-legal volunteers, and IT systems are all involved shows that there is a multi-pronged approach to systemic transformation that combines legal, administrative, and technical answers.

The Supreme Court of India made a compassionate but forceful move in In Re: Compensation Amounts Deposited with Motor Accident Claims Tribunals and Labour Courts to close the gap between the legal recognition of rights and their enforcement in the actual world.

The Court’s involvement is timely, important, and effective since there are crores of money sitting around while victims and their families suffer.

Justice Oka and Justice Bhuyan have written an order that is both imaginative and practical. It demonstrates the way judicial activism can introduce change in the system. The ruling is a reminder that courts do not only serve as places where people resolve their disputes, but also serve as courts of justice which ensure that every person is subjected to fair treatment, equal treatment and is treated with dignity both on paper and in the real sense of the word.