In the case of New Mangalore Port Trust and Others v. Clifford D’Souza and Others, which was heard by the Supreme Court of India in April 2025, a key ruling was handed down. This case addressed a significant legal matter about the time period within which public authorities have the ability to recover dues from users of public property, such as license payments.

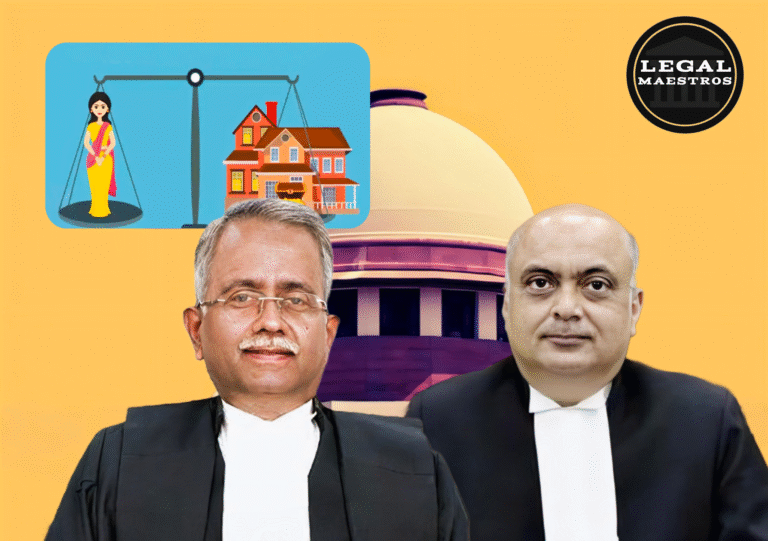

The judgment was handed down by Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Prasanna B. Varale, and it centers on the question of whether or not the Limitation Act is applicable to actions that were begun under the Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorised Occupants) Act, 1971 (PP Act).

Context and some important facts

A statutory organization known as the New Mangalore Port Trust (NMPT) had begun leasing land to a number of licensees (respondents) in the year 2003 for the purpose of carrying out activities that were associated with loading and unloading cargo.

It was stipulated in the lease agreements that the licensing fee would be subject to periodic revisions based on rates that have been approved by the Tariff Authority for Major Ports (TAMP).

In spite of the fact that a change was made in 2010, it was implemented with retroactive effect beginning in February of 2007. When the NMPT filed a demand letter in 2011, they were looking for arrears for the time period that had passed.

By submitting writ petitions to the Karnataka High Court, the licensees disputed the retrospective revision that had been implemented. Their applications were denied by the Single Judge in 2013, who was of the opinion that retrospective modification was within the bounds of the law. Subsequently, the licensees submitted appeals inside the court, which are still pending.

Even though there were appeals that were still pending, the NMPT continued to send out demand notifications, including a last notice that was dated January 15, 2015. A response was given by the licensees, who argued that it was impossible to demand payment while the case was still being heard in court.

Eventually, in August of 2015, the Estate Officer initiated actions in accordance with the personal property act. The district judge concluded that the recovery actions were not allowed because of the statute of limitations, which led to the challenges and subsequent dismissal of these. As a result of the High Court’s subsequent decision to uphold this ruling, NMPT filed an appeal with the Supreme Court.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

Crucial Questions in the Law

To determine whether the NMPT’s demand for arrears of license fees issued through the PP Act was legally valid or if it had passed the statute of limitations, the Supreme Court was urged to make a decision. Particular inquiries included the following:

The question at hand is whether or not the three-year limitation term that is stipulated in Article 52 of the Limitation Act applies to demands related to the PP Act.

In accordance with Section 18 of the Limitation Act, investigate whether or not an acknowledgment of liability on the part of the respondents could lengthen the limitation period.

Given the preceding correspondence, the question at hand is whether or whether the procedures that were begun in 2015 under Section 7 of the PP Act were within the acceptable time range.

In spite of ongoing challenges against the tariff revision, the question is whether or not the Estate Officer operated within the bounds of the law when pursuing recovery procedures.

Discussions by the NMPT

In a written response dated February 4, 2015, the National Maritime Press (NMPT) stated that the limitation period had to be computed from the moment that the respondents acknowledged that they were in possession of dues.

An acknowledgment of this kind is required to resume the limitation period in accordance with Section 18 of the Limitation Act. In their argument, NMPT said that this reset the clock, and as a result, the notification that was sent in August 2015 fell within the expanded three-year timeline.

In addition, the NMPT held that even if the Estate Officer delivered letters a little bit later, the licensees should not benefit from the absence of objections to limitation in their responses.

It was their contention that the only reason the licensees had delayed payment was because the appeal was still pending, and not because they had denied any culpability.

The Licensees’ Arguments and Concerns

As a result of the fact that the new tariff was notified in 2010, and the notice under Section 7 of the PP Act did not come until August 2015, the licensees argued that the claim was plainly time-barred.

They stated that within the three-year limitation period, there was no statutory notification delivered in accordance with the PP Act. In addition, they contested the assertion made by NMPT that their response constituted an acknowledgment in accordance with Section 18, stating that they had never admitted any liability and had simply requested a postponement until the appeal was resolved.

In addition, they contended that the National Maritime Police Service (NMPT) did not bring up the Section 18 plea in the lower courts, and that it should not be permitted to do so for the first time in the Supreme Court.

Furthermore, they emphasized that the duty of the Estate Officer needed to be clearly distinguished from the general administrative tasks of the NMPT, and that prior letters from the NMPT should not be considered to be statutory notices.

Observations Made by the Supreme Court

Despite the fact that both parties had delayed bringing crucial legal challenges at the appropriate time, the Supreme Court acknowledged that it would nonetheless rule the matter based on facts that were not in question.

Following the clarification provided by earlier case law, in particular the Kalu Ram decision, the Court reached the conclusion that the Limitation Act was applicable to the PP Act.

After reviewing the response that the respondents provided on February 4, 2015, the court came to the conclusion that it did constitute an acknowledgment of liability in accordance with Section 18 of the Limitation Act.

The letter did not contradict the dues; rather, it merely requested that the demand be postponed while an appeal was being considered. From the date of the acknowledgment, the limitation period is extended by an additional three years in accordance with Section 18, which states that such an acknowledgment.

In light of this, the limitation was extended all the way up to February 2018, and the notification that the NMPT issued in accordance with the PP Act in August 2015 was well within the amended time limit.

The High Court was the target of criticism from the Court because it failed to take this into consideration and instead computed limitation based purely on the date of the initial notification, which was in 2010.

The significance of the sixteenth section of the Limitation Act

The case placed a significant amount of focus on Section 18 of the Limitation Act, which stipulates that the limitation period might begin again from the date that the obligation or liability was acknowledged.

A conditional or partial acceptance is sufficient, according to the Court’s explanation, provided that it is written down and signed by the parties involved. It was determined that the response from the licensees, which said that the amount was not denied but rather postponed owing to the pending appeal, was sufficient to qualify under this condition.

The judgment also reaffirmed that one must take into consideration all of the provisions of the Limitation Act, including Section 18, once it has been determined that the Act meets the requirements.

The ultimate choice

A ruling that had been made by the High Court was overturned by the Supreme Court, which granted NMPT’s appeal. The writ petitions that were submitted by NMPT were reinstated, but it was ruled that they would not be considered until the Division Bench of the Karnataka High Court had made a decision regarding the ongoing intra-court appeals that were submitted by the licensees themselves.

The recovery actions will be automatically terminated in the event that the appeals are successful and the retrospective tariff revision is rendered invalid. Nevertheless, in the event that the appeals are rejected, the demand made by the NMPT would be sanctioned, and the dues would be required to be paid along with any applicable interest.

Further-Reaching Consequences

The implications of this verdict are substantial for statutory bodies and government entities who are responsible for managing public property and buildings. It reaffirms that limitation laws do, in fact, apply to recovery processes that are conducted in accordance with the PP Act, but it also makes it clear that parties who wish to avoid limitation concerns must be careful about what they write.

The limitation period may be restarted by any response that acknowledges a debt, even if the response does not specifically promise payment of the debt amount.

Furthermore, the judgment emphasizes the necessity for courts to take into consideration all applicable legal requirements, including Section 18, even if they were not brought up in previous stages of the process, given that the facts are not in question.

The decision that was handed down in the case of New Mangalore Port Trust v. Clifford D’Souza provides valuable direction about the computation of limitation periods in recovery matters that fall under the purview of the PP Act.

It places an emphasis on the significance of written acknowledgments, the equitable application of procedural timetables, and the significance of judicial coordination in situations where similar actions are pending before multiple benches. The decision assures that public bodies are not unduly deprived of lawful dues due to technicalities, while simultaneously maintaining procedural fairness for those who are facing recovery actions.

For any queries or to publish an article or post on our platform, please email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.