In the case of G.C. Manjunath and Others v. Seetaram, which was heard by the Supreme Court of India in April 2025, the court issued a landmark verdict that addressed the legal prerequisites for prosecuting public officers.

The most important question was whether or not it was possible to commence criminal actions against police officers without first receiving authorization from the government. During the course of their duties, public officials should be protected from frivolous or retaliatory litigation, but they should also be held accountable for their actions. This case brought to light the delicate balance that must be maintained.

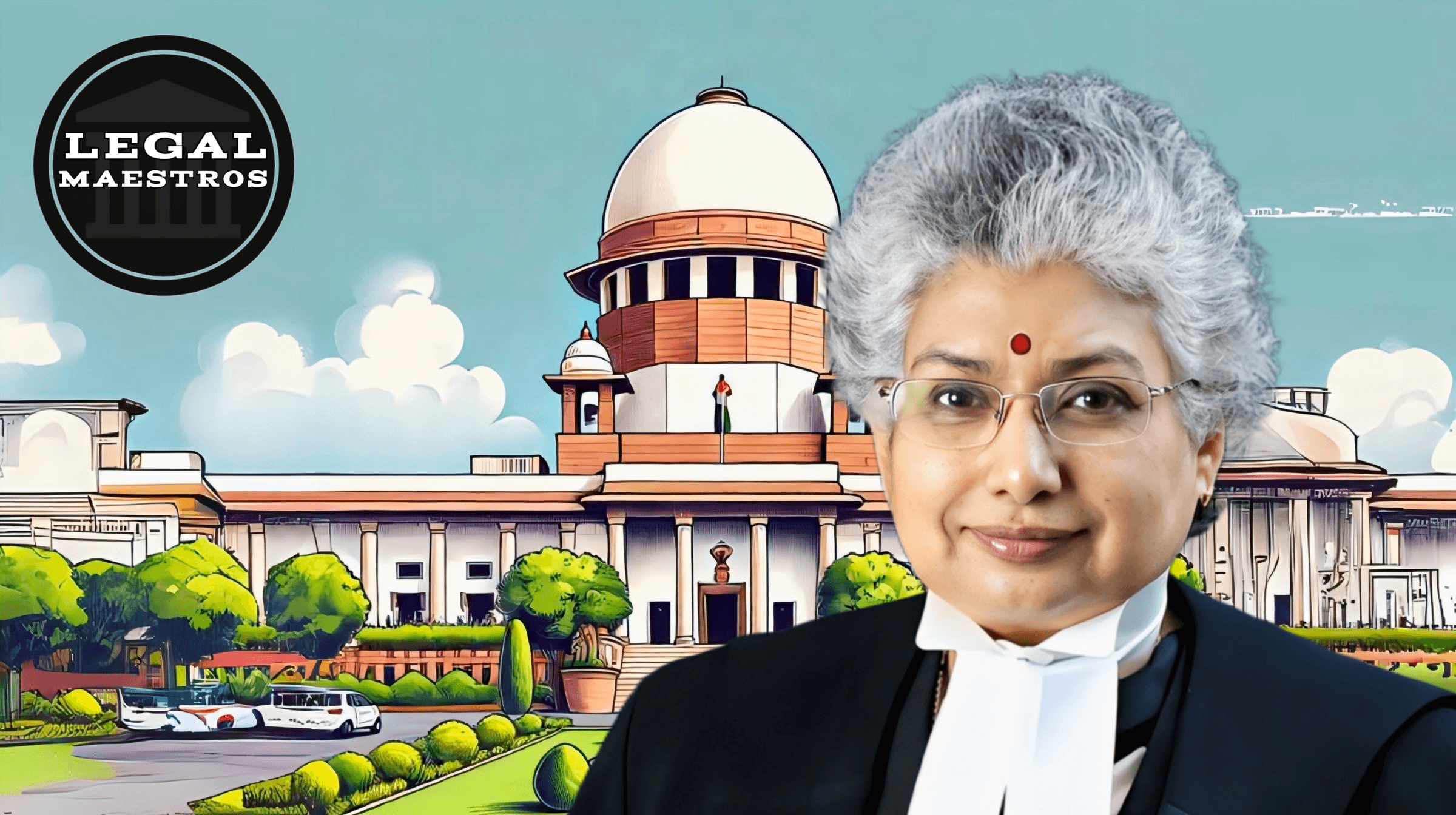

The judgment that was written by Justice B.V. Nagarathna, with Justice Satish Chandra Sharma concurring, provided clarification regarding the manner in which and the circumstances under which the statutory protections outlined in Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) and Section 170 of the Karnataka Police Act, 1963 ought to be applied.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Historical context and the facts of the case

Seetaram, the person who filed the complaint, has a history of getting into trouble with the law enforcement and had been labeled as a rowdy sheeter in the past. He claimed that he was subjected to harassment and torture at the hands of multiple law enforcement personnel as a result of his role in revealing certain illegal actions that were being carried out by other officials. The appellants in this case, G.C.

Manjunath and another officer, are among the police officers who beat and humiliated him while he was in detention, according to his claims. These assaults occurred in 1999 and occurred during two different incidents.

The individual who filed the complaint claimed that the cops had unlawfully detained him, assaulted him physically, and publicly slandered him, including publishing his photograph against his will in a media publication. In 2007, eight years after the claimed incidents, he filed a private complaint against six accused persons, including the appellant officers.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The complaint was filed against the appellant officers. The magistrate began the process of initiating criminal proceedings after taking cognizance of the situation.

The policemen who were suspected of wrongdoing disputed the proceedings, alleging that the law had not been followed and that there was no sanction established for prosecution.

Their petition, on the other hand, was rejected by the Karnataka High Court, which stated that the claimed conduct were not connected to official duties and, as a result, did not require prior authorization. This gave rise to the appeal that was filed with the Supreme Court.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Provisions of the Law That Are Critically Important

Both Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code and Section 170 of the Karnataka Police Act were the fundamental legal elements that were under issue.

According to the provisions of Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code, no court is permitted to take cognizance of any offense that is alleged to have been committed by a public servant while acting or pretending to act in the course of their official duties without first receiving authorization from the government.

It is the intention of this proposal to shield public servants from unwarranted harassment for actions that they carry out in good faith while doing their duties.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

A comparable level of protection is afforded to law enforcement personnel by Section 170 of the Karnataka Police Act. According to this provision, prosecutions for acts that were carried out under color or in excess of official duties are not permitted to begin without the prior approval of the government.

Collectively, the purpose of these rules is to prevent the criminal justice system from being abused against government officers who, in the course of their duties, act in a manner that is appropriate, even if it is erroneous.

Issues that have been brought forward by the appellants

Despite the fact that some of the acts taken were deemed to be excessive, the appellants maintained that all of the actions taken were in the course of official obligations. According to their argument, the actions that were being criticized—arrests, searches, and custody—were inextricably tied to the duties that they were expected to fulfill as police officers.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Therefore, the court would not have been able to take cognizance of the offenses because there was no prior sanction from the government.

They relied on a number of earlier decisions made by the Supreme Court, most notably D. Devaraja v. Owais Sabeer Hussain and Virupaxappa v. State of Mysore, in which the Court had ruled that even actions that appear to be excessive or illegal can be protected by Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code if they are reasonably connected to official duties.

In addition, the appellants stated that the delay in making the complaint—nearly eight years after the alleged events—was a vindictive effort in response to the fact that the complainant had been found not guilty in earlier cases.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Complainant’s Response on the Matter

The individual who filed the complaint, Seetaram, highlighted, through his legal representative, that the police officers had gone beyond the bounds of their duties by demeaning and physically abusing him. Furthermore, he asserted that their actions, which included stripping him, beating him with rods, and publishing disparaging images, were so far removed from genuine police activity that they could not be protected by the law.

In addition, he argued that he had made an effort to get sanction, but the authorities had not responded to his request.

As a result, he should not be fined for administrative delays. In order to provide evidence in support of his allegations of abuse, medical documents and images of injuries were submitted.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The arguments were accepted by the High Court, which came to the conclusion that the claimed activities did not have any legitimate connection to the performance of police responsibilities. As a result, the court decided that there was no need to impose any consequence.

An Examination and Observations Made by the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court started off by highlighting the significance of both Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code and Section 170 of the Police Act in terms of safeguarding honest public officials from litigating criminal cases that are not essential.

The Court made it clear that the most important assessment is whether or whether the behavior in question is “reasonably connected” to the execution of official responsibilities.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The decision stated that the expression “under color of duty” include actions that may go beyond the authority that has been granted to the officer, but are carried out within the context of official tasks being carried out.

As long as there is a plausible relationship between the act and the official obligation, protection under the law is applicable. This is true even if the act entails misusing or exceeding the authority that is granted to it.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed, with reference to the case of D. Devaraja, that engaging in conduct that are excessive or improper does not automatically prohibit a public servant from receiving legal protection. In spite of the fact that the law does not anticipate public officials to be flawless, it does mandate that there be a connection between the action taken and the task that was carried out.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In this particular case, the court took note of the fact that the complainant had been diagnosed as a rowdy sheeter, and that the alleged incidents occurred within the course of investigations and arrests that were carried out by the police.

In spite of the seriousness of the charges, the court came to the conclusion that these actions were not completely unrelated to the official position that the officers played.

Decisions and judgments that are final

The appellants were successful in their argument before the Supreme Court. It was determined that because the activities were connected to the performance of police responsibilities, regardless of how extreme or unlawful they were, the law required that prior sanction from the state be acquired before the criminal courts could take cognizance of the situation.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In light of the fact that such a sanction was not acquired, the proceedings that were brought against the accused were disregarded from the very beginning. The summoning orders, the verdict handed down by the Sessions Court, and the decision handed down by the High Court were all overturned.

Additionally, the Court took into consideration the amount of time that had passed. In light of the fact that the occurrences occurred in 1999 and that three of the accused had already passed away, the court determined that it would serve no purpose to permit the criminal procedures to continue against the two retired officers who were still alive, particularly given their advanced age.

Since this was the case, the appeal was granted, and the criminal prosecution that had been brought against the appellants was dismissed.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

This decision represents a significant reaffirmation of the legal protections that are afforded to staff members of the public sector. In spite of the fact that it does not provide immunity for offenses of any kind, it makes it very apparent that in situations where there is a plausible relationship between the act and official obligations, the courts are not permitted to proceed with criminal prosecutions without first receiving authorization from the government.

Through the ruling in G.C. Manjunath v. Seetaram, the integrity of public administration is safeguarded. This is accomplished by preventing the misuse of the criminal procedure against officials who operate within their professional obligations, regardless of whether they are doing lawfully or wrongly.

At the same time, it emphasizes that accountability must adhere to due process and cannot choose to disregard statutory safeguards. This case serves as a reminder that justice necessitates not just fair trials but also protection from unfair prosecution.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

![Research Assistantship @ Sahibnoor Singh Sindhu, [Remote; Stipend of Rs. 7.5k; Dec 2025 & Jan 2026]: Apply by Nov 14, 2025!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_s0k4u6s0k4u6s0k4-768x707.png)

![Karanjawala & Co Hiring Freshers for Legal Counsel [Immediate Joining; Full Time Position in Delhi]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_52f8mg52f8mg52f8-768x711.png)