The Supreme Court of India issued a key order on April 7, 2025, which reaffirmed the notion that a person is presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This ruling was important since it strengthened the principle.

The unfortunate death of a young married woman was the subject of the case Jagdish Gond v. State of Chhattisgarh. The death was first recorded as being unnatural before the action was brought.

In spite of the fact that the husband was found not guilty by the lower court, the High Court overturned the acquittal and found him guilty of murder in accordance with Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Supreme Court, on the other hand, made the decision to reinstate the acquittal, determining that the verdict handed down by the High Court was founded solely on suspicion and lacked substantial proof.

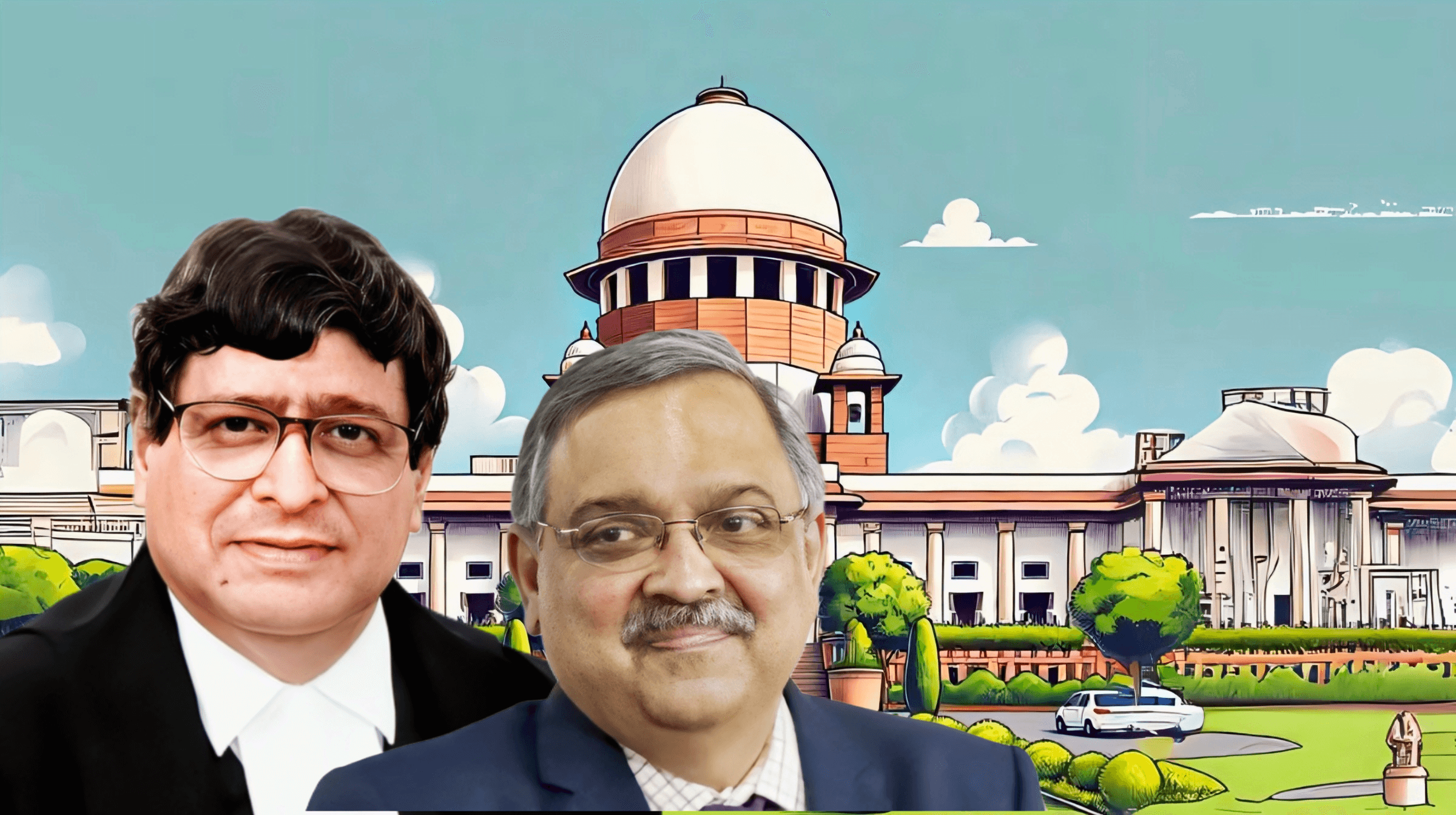

The ruling was written by Justice K. Vinod Chandran, and Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia concurred with his opinion. The presumption of innocence, circumstantial evidence, and the burden of proof associated with criminal law are some of the fundamental legal concepts that are discussed in this book.

An Overview of the Facts

While she was still living with her husband Jagdish Gond, the deceased woman had only been married for a short period of time—two years. Jagdish stated that he had come from his night shift at a cement factory on the morning of January 29, 2017, and saw his wife lying dead on the cot inside their home.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

He claimed that he had discovered her body. Due to the fact that the door was fastened from the inside, it had to be broken open. Almost immediately, he contacted both his parents and the authorities in the area. It was a case of unexpected and unnatural death, and the initial report was submitted under Section 174 of the Criminal Procedure Code with the appropriate authorities.

Neither the relatives nor the police had any suspicions about the circumstances surrounding the death at the time of the inquiry. However, five days later, the deceased’s father filed a complaint against Jagdish and his family, alleging that they had harassed the deceased and were ultimately responsible for her passing from the circumstances surrounding her death.

As a result of the complaint, a case was filed under Sections 498A and 306 of the Indian Penal Code (cruelty and abetment to suicide), as well as Section 302 of the IPC (murder). The case was litigated in court.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

Verdict of the Trial Court

Following the examination of the medical evidence and the testimony of eight witnesses, the trial court came to the conclusion that the death could not be proven to be the result of a murder.

The court decided that there was no conclusive evidence to show culpability, and there was also no chain of circumstantial evidence to demonstrate fault. According to the postmortem report, there was a ligature mark on the front of the neck as well as a fracture of the cricoid cartilage; however,

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

the medical expert was unable to determine if the death was the result of hanging, strangling, or suicide. Nobody else was hurt, and there were no further indications of violence.

The court took note of the lack of tangible proof as well as the contradictions that were present in the testimony of witnesses. All three defendants, including Jagdish and his in-laws, were found not guilty.

The Reversal of the High Court

The acquittal of the in-laws was affirmed by the High Court when the State filed an appeal; however, the acquittal of Jagdish was overturned. He was found guilty of violating Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code and was given a sentence of life imprisonment.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

According to the reasoning of the High Court, Jagdish was required to provide an explanation for his wife’s death in accordance with Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act because he and his wife lived together.

Furthermore, it stated that he had failed to offer evidence that supported his alibi, which was that he was on duty at the time of the incident.

This reverse was litigated before the Supreme Court of the United States.

Legal Matters That Are Taken Into Account by the Supreme Court

The United States Supreme Court deliberated on two significant issues:

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In the absence of conclusive evidence of homicide, the question of whether or not the High Court was warranted in overturning the acquittal.

The question in question is whether or not the husband’s inability to provide an alibi might be the sole grounds for conviction.

In its decision to reverse acquittals, the Supreme Court underlined that appellate courts must proceed with extreme caution.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The presumption of innocence continues to strengthen after an accused person has been found not guilty by a trial court. In order to reverse a decision, there must be evidence that the reasoning of the lower court was gravely flawed or erroneous.

Consideration of the Evidence

Each and every piece of evidence was examined in great detail by the Supreme Court. The first item that was brought to the attention of the court was the fact that the husband himself had reported the unnatural death, and that he had been accompanied by the village Kotwar.

This was an indication of innocence and transparency. This version was promptly recorded by the police, and it included his assertion that he had gone to work the night before.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

There was not a single suspect of murder that was offered at the inquest. The later statements of the deceased person’s family, who claimed to have guessed that the deceased person had been strangled at the time of death, were refuted by this. This contradiction was deemed to be problematic by the Court.

The medical report was unable to provide a conclusive answer about whether the death was the result of homicide or suicide. The pattern of the ligature was only found on the front of the neck, which did not correspond to the traditional indications of strangulation or hanging.

According to the physician, the cause of death was asphyxia brought on by compression of the trachea. However, the physician also mentioned that the nature of the death, whether it was homicidal or suicidal, was a topic that needed to be investigated.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It was recognized by the court that the absence of any exterior injuries or other evidence that provided support rendered it impossible to determine beyond a reasonable doubt that the death was the result of a murder.

Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act and the concept of an alibi

The High Court had placed a significant amount of weight on Section 106, which stipulates that a person is responsible for proving facts, particularly those that are within his or her understanding. Given that Jagdish and his wife were cohabitating, the High Court anticipated that he would clarify the circumstances surrounding her passing.

The Supreme Court, on the other hand, came to the conclusion that this presumption cannot be more powerful than the primary burden that the prosecution bears to show guilt. The fact that Jagdish’s alibi was mentioned from the very beginning in the police record was brought to light, and it was not something that was invented later on.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Due to the fact that the police did not verify his work attendance, it would not be considered fair to invalidate his argument purely on the basis that he was unable to provide evidence that he was there at work.

In situations when the prosecution is unable to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty, the Court highlighted that Section 106 cannot be the sole basis for that conviction.

Evidence based on circumstantial evidence and the requirement for a full chain

In instances that rely on circumstantial evidence, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that the chain of evidence must be complete and must reject every other hypothesis but guilt.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In this particular case, the court did not discover any chain of events. No eyewitnesses were present, there was no evidence of a motive, and there was no credible medical opinion that established the murder.

The fact that a young married woman passed away in her house in an unnatural manner was not sufficient to convict someone of murder, particularly when there were other possible causes for her death.

The ultimate verdict

Jagdish Gond was found guilty by the High Court, but the Supreme Court overturned that judgment and reinstated the order of acquittal that was issued by the trial court. Not only did it annul any bail bonds that had been executed, but it also ordered his immediate release if it was not required in any other case.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Despite the fact that the death was tragic, the court came to the conclusion that it could not be considered a murder. It issued a warning to the judicial system from allowing emotional emotions to take precedence over legal requirements of proof.

The ruling in the case of Jagdish Gond v. State of Chhattisgarh serves as an important reminder of the fundamental principles that underpin the administration of criminal justice. These principles include the presumption of innocence, the burden of proof being placed on the prosecution, and the requirement of conclusive evidence.

By highlighting the fact that suspicion, regardless of how strong it may be, cannot serve as a substitute for proof, the Supreme Court safeguarded fundamental foundations. The decision ensures that assumptions do not jeopardize the administration of justice and drives home the point that the rule of law must take precedence over speculation.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

![Research Assistantship @ Sahibnoor Singh Sindhu, [Remote; Stipend of Rs. 7.5k; Dec 2025 & Jan 2026]: Apply by Nov 14, 2025!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_s0k4u6s0k4u6s0k4-768x707.png)

![Karanjawala & Co Hiring Freshers for Legal Counsel [Immediate Joining; Full Time Position in Delhi]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_52f8mg52f8mg52f8-768x711.png)

![Part-Time Legal Associate / Legal Intern @ Juris at Work [Remote]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_08_41-PM-768x768.png)

![JOB POST: Legal Content Manager at Lawctopus [3-7 Years PQE; Salary Upto Rs. 70k; Remote]: Rolling Applications!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_01_56-PM-768x768.png)

1 thought on “Justice k. vinod chandran and Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia on Why Suspicion Is Not Evidence in Jagdish Gond Case”