It was in the case of Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir v. Brij Bhushan that the Supreme Court of India reinforced the idea that the prosecution of criminal cases must be founded on actual claims and tangible evidence.

At the heart of the case was a land deal that took place in 1989 and involved the Jammu and Kashmir Cooperative Housing Corporation (JKCHC). Additionally, a First Information Report (FIR) was filed in 2021, stating that there was a criminal conspiracy and instances of corruption.

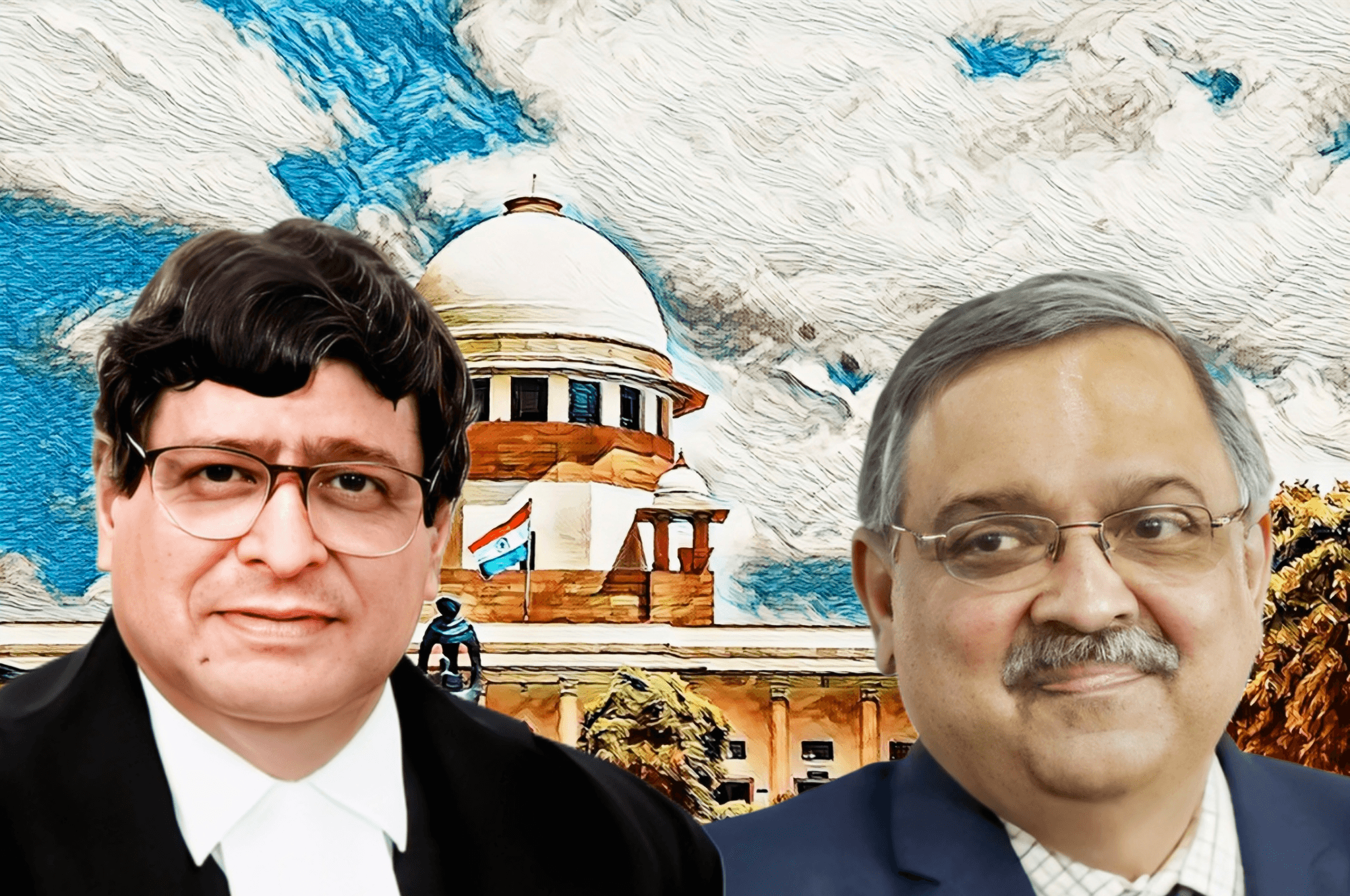

The decision of the High Court to dismiss the First Information Report (FIR) filed against Brij Bhushan, who was serving as the Managing Director of JKCHC at the time, was affirmed by the Supreme Court in its judgment that was handed down on April 7, 2025 by Justices K. Vinod Chandran and Sudhanshu Dhulia.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Considering that there were no specific charges of personal benefit or fraudulent purpose, the court came to the conclusion that there was no grounds for initiating criminal proceedings more than three decades after the transaction.

Historical Context of the Case

To acquire around 30 kanals and 5 marlas of land for the purpose of building residential colonies, the JKCHC entered into a deal in 1989. This was done in order to establish residential colonies.

The society went on to create dwelling blocks that were distributed to its members on a first-come, first-served basis after this transaction was formalized through a registered lease deed before the society moved on to develop housing blocks. It was around that time that Brij Bhushan held the position of Managing Director at the JKCHC.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Under the provisions of Section 5(2) of the Jammu and Kashmir Prevention of Corruption Act, 2006 and Section 120-B of the Indian Penal Code, a First Information Report (FIR) was submitted in the year 2021.

Brij Bhushan was accused of violating the Jammu and Kashmir Agrarian Reforms Act, 1976, by unlawfully obtaining a land verification certificate known as a “fard intikhab” and fraudulently facilitating the transfer of state-vested land to JKCHC. The FIR alleged that Brij Bhushan had done this in conjunction with a Tehsildar and a power of attorney holder of the landowners.

The First Information Report (FIR) was dismissed by the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, which accepted Brij Bhushan’s appeal in accordance with Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. A challenge was brought before the Supreme Court by the Union Territory over the ruling made by the High Court.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

The legal provisions that are at the heart of the disagreement

Interpretation of a number of different legal clauses was involved in this case:

In accordance with the Prevention of Corruption Act, Section 5(2), public workers who take reward or abuse their position for the sake of personal gain are subject to criminal prosecution.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In the Indian Penal Code, Section 120-B addresses criminal conspiracy.

In the Jammu and Kashmir Agrarian Reforms Act, Section 28(1)(d) and Section 28-A include provisions that prohibit the transfer of land that has been awarded in accordance with the Act.

Furthermore, these provisions indicate that any illegal transfer of property should result in the land being returned to the State.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Additionally, public officials are afforded protection under Section 29 of the same Act for actions that are carried out in good faith.

According to Section 482 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the High Court has the authority to dismiss criminal proceedings if it is determined that the complaint is malicious or without foundation.

Observations made by the nation’s highest court

The Supreme Court conducted a thorough investigation into the kind of charges that were contained in the FIR. According to the report, the respondent, Brij Bhushan, had only served in the capacity of Managing Director of a cooperative society that had bought land for the purpose of providing public benefit, specifically for the creation of homes.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Even after more than thirty years, the state had not taken any action to reclaim or reverse the transaction, despite the fact that the transfer was carried out using a registered lease deed.

The court emphasized that the landowners had been properly designated a power of attorney holder who spoke with the Tehsildar and that the landowners had been vested with the land by the state.

The ‘fard intikhab’ was one of the documents that the cooperative organization acted upon by simply acting upon paperwork given by revenue authorities. There was not a single shred of evidence to suggest that Brij Bhushan abused his position or obtained any further personal profit from the transaction.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Supreme Court underlined that the First Information Report (FIR) contained only hazy claims of “connivance” that were not supported by precise particulars or facts. In the area of criminal law, particularly in cases where public personnel are implicated, the level of evidence and detail that is required is extremely high.

It is necessary for allegations to demonstrate to personal advantage, dishonest intent, or willful misbehavior; however, none of these attributes were discovered in this particular instance.

What Function Does the Agrarian Reforms Act Serve?

The claim that the transaction ran counter to Section 28 of the Agrarian Reforms Act, which prohibits the sale or transfer of land that has been awarded under the Act, was the foundation upon which the State’s case was formed.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

On the other hand, the Supreme Court decided that administrative consequences, such as the return of land to the state, are the only ones that are triggered by such violations. In and of itself, they do not constitute sufficient grounds for criminal prosecution, barring the presence of evidence of fraud or corruption.

In spite of the fact that the transaction was in violation of the Agrarian Reforms Act according to its letter, the court observed that the state had not taken any action in accordance with Section 28-A to either resume ownership or cancel the lease.

Consequently, it was not suitable to use the FIR as a means to begin criminal proceedings.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In addition, Section 29 of the Act provides protection for public personnel who are acting in truthful manner. When Brij Bhushan acted, there was no evidence to suggest that he did so with malicious intent.

The acts he took were administrative in nature and were a component of a larger public aim, which was the development of inexpensive housing.

Existence of the Presumption of Innocence and the Limits of Criminal Law

It was emphasized by the Supreme Court that criminal law should not be abused in order to examine administrative measures that were conducted decades ago without any new or credible evidence.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Additionally, the Court made it plain that public servants, particularly those who are functioning in representative capacity for cooperative institutions, should not be subjected to harassment through the use of vague FIRs unless the allegations clearly amount to criminal activity.

The Supreme Court went on to make it clear that even though anti-corruption statutes are stringent, they should not be administered in a careless manner.

According to the Prevention of Corruption Act or the Indian Penal Code, not every error in procedure or breach of the statute constitutes a criminal offense.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It is necessary to provide evidence that is both clear and convincing in order to prove that an individual conspired to misuse public power or enabled unlawful gains. However, none of these types of evidence were present in this particular instance.

The Supreme Court’s Final Decision on the Matter

The Special Leave Petition was denied by the Supreme Court, and the judgment of the High Court to dismiss the FIR was approved by the Supreme Court. The FIR was determined to be founded on assumptions rather than evidence, according to the findings.

The fact that there was no personal benefit, the fact that the transaction was public, and the fact that the state did not take any action in accordance with the applicable land legislation all provided support for the point of view that there was no illegality.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The court made the observation that permitting the FIR to proceed would not serve the purpose of justice; rather, it would involve the respondent and the judicial system being burdened with a prosecution that was without foundation.

Underscoring the notion that criminal prosecution cannot be used as a means of settling administrative doubts or political disagreements, particularly after the passage of time and in the lack of tangible proof, the decision highlights the fact that this principle cannot be applied.

The decision that the Supreme Court made in the case of Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir v. Brij Bhushan is a significant precedent that is applicable to instances that include anti-corruption statutes and administrative proceedings that have been in place for a long time.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It makes a distinct distinction between instances of procedural irregularity and instances of criminal wrongdoing, and it emphasizes the significance of protecting individuals from criminal proceedings that are both unnecessary and unfair.

In addition to protecting the dignity of individuals, the judgment also safeguards the operational independence of cooperative organizations and administrative bodies. This is accomplished by strengthening the criteria that must be met in order to initiate criminal actions against public personnel.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

![Research Assistantship @ Sahibnoor Singh Sindhu, [Remote; Stipend of Rs. 7.5k; Dec 2025 & Jan 2026]: Apply by Nov 14, 2025!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_s0k4u6s0k4u6s0k4-768x707.png)

![Karanjawala & Co Hiring Freshers for Legal Counsel [Immediate Joining; Full Time Position in Delhi]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_52f8mg52f8mg52f8-768x711.png)

![Part-Time Legal Associate / Legal Intern @ Juris at Work [Remote]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_08_41-PM-768x768.png)

![JOB POST: Legal Content Manager at Lawctopus [3-7 Years PQE; Salary Upto Rs. 70k; Remote]: Rolling Applications!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_01_56-PM-768x768.png)