Introduction

On 1st December 2025 Apex Court issued notice in a PIL filed by Sameeksha foundation by Mr. Devansh Srivastava as the Advocate-on-Record (AoR) to Union Government regarding 20 year long inaction by the executive to frame statutory rules for prosecuting medical professionals in case of gross medical negligence, a mandate from the 2005 Jacob Mathew V. State of Punjab judgment. This article will analyse the legal vacuum, the transition from IPC and BNS, and the systematic bias of the notion that doctors will judge negligence of doctors.

Keywords: Medical Negligence, Supreme Court, Jacob Mathew, BNS Section 106, Sameeksha Foundation, Doctors Judging Doctors, Parliamentary Committee Report.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

1. The Genesis of the Crisis: The 2025 Supreme Court Notice

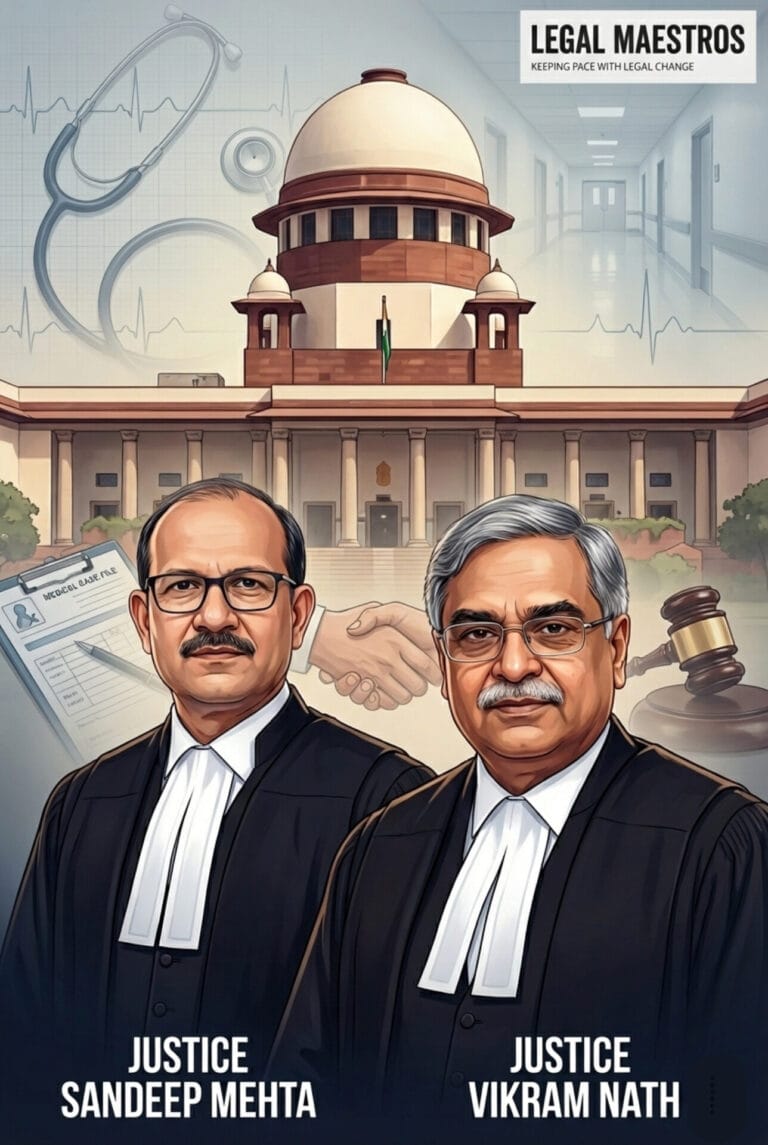

On December 1, 2025, Hon’ble Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta issued a notice to the Centre, questioning the two-decade delay in framing guidelines for the criminal prosecution of doctors.

The Petitioner’s Case

The PIL establishes case against the centre that it has not performed its constitutional duty by framing the statutory rules along with National Medical Council (NMC) of India as directed in Jacob Mathew judgment.

- Executive Inertia: The petitioner cited a May 2025 RTI response from the NMC, which admitted that “no such guidelines have been framed” and the matter remained “under process” even after the passage of 20 years.

- The Statistical Gap: The plea highlights a massive disparity between the estimated 5.2 million annual incidents of medical malpractice and the minuscule number of criminal cases registered approximately 1,019 over six years according to National Crime Records Bureau data. The petitioner argues this proves the current system creates immunity for the doers and victims suffer due to lack of a proper mechanism to file a complaint against medical professionals.

2. Jurisprudential Anchor: Jacob Mathew v. State of Punjab (2005)

The current legal framework is entirely relied upon the stopgap guidelines issued in Jacob Mathew judgment, which distinguished between criminal and civil liabilities of medical professionals emphasizing that criminal liability requires a serious or gross misconduct or a clear departure from the standard medical procedure.

- Gross Negligence: The Court held that for criminal liability, the negligence must be gross or reckless, showing a total disregard for patient safety and the standard procedures established in medical science.

- The Interim Guidelines: To prevent unnecessary harassment, the Court made it a mandate that police must obtain an independent medical personnel opinion before acting upon the complaint. The intention of these guidelines was to create a temporary solution to the problem of medical negligence until legislation was passed but legislation never materialized.

3. The Core Conflict: “Doctors Judging Doctors”

The central grievance of the PIL is that the independent medical opinion mechanism has mutated into a shield against accountability.

- Systemic Bias: Inquiry committees are typically staffed exclusively by government doctors who often sympathize with the accused professional due to fraternity solidarity.

- Parliamentary Findings: The petitioner relies on the 73rd Parliamentary Standing Committee Report (2013), which explicitly noted that medical professionals are very lenient towards their colleagues and unwilling to testify against one another which clearly highlights that exists when doctors judge each other in cases of medical negligence cases. The Committee recommended including non-medical members in inquiry panels to ensure impartiality a recommendation ignored for more than a decade.

4. The Legislative Shift: IPC vs. Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

The debate is complicated by the transition from the Indian Penal Code (IPC) to the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) in 2023/2024.

Under IPC Section 304A, causing death by negligence was punishable by imprisonment up to two years OR a fine. This gave courts discretion to impose only a fine.

BNS Section 106(1) changes this dynamic by introducing a mandatory imprisonment clause in the section:

- It states that a registered medical practitioner “shall be punished with imprisonment of up to 2 years… and shall also be liable to fine”.

- Legal Interpretation: The use of “and” implies that imprisonment is now mandatory upon conviction, now the judicial discretion to let off doctors with just fine is unavailable to the judges.

- Medical Protest: The Indian Medical Association (IMA) has strongly opposed this, arguing that mandatory jail time for errors of judgment will force doctors into defensive medicine, refusing critical cases to avoid liability.

| Feature | IPC Section 304A | BNS Section 106(1) |

| Punishment | Imprisonment OR Fine OR Both | Imprisonment AND Fine |

| Implication | Discretionary Jail Time | Mandatory Jail Time |

5. Comparative Frameworks & Solutions

The PIL suggests India must move away from exclusive peer review and move toward a more all-inclusive approach in which not only just doctors but other members of civil society take part in the investigation of complaints.

- The UK Model: In United Kingdom, the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS), works on issues related to medical malpractice. Mainly, these institutions have lay members who are non-doctors and often legally qualified chair, ensuring doctors are not sole judges of their peers.

- Proposed Reform: The PIL demands Hybrid Inquiry Panels comprising retired judges, civil society members, and patient representatives alongside doctors. This would balance technical expertise with public accountability and will help both the medical professionals and common public by easing the mechanism of complaint filing and transparent resolution of the same.

6. Conclusion

The Apex Court’s intervention became quite necessary seeing the clear overlook by the parliament of this legislative vacuum. The current stopgap system satisfies no one: patients feel denied of their right to justice due to peers reviewing peers, while doctors feel intimidated by the mandatory imprisonment provisions laid down by the legislation. A balanced statutory framework is needed to address this multi-dimensional problem and clarification on the standard of gross negligence is needed to restore faith of common public in medico-legal ecosystem.