Indian News Channels: Criminal and Media Law Implications for Warmongering

Introduction

Within the past few years, a multitude of Indian television news networks have been accused of developing a tone that may be described as “warmongering.” In light of this, it is possible that they will advocate for a military response that is aggressive in their reporting, particularly with reference to India’s ties with nations that are its neighbors. These kinds of operations give rise to significant issues in terms of India’s criminal laws and media regulations. At the same time as journalists have the right to express themselves freely, they also have the responsibility to report in a responsible manner. Both criminal consequences and regulatory action may be taken against broadcasts that cross the line into inciting hatred or inciting others to act in a hostile manner.

Comprehending the Role of Warmongering in the News Media

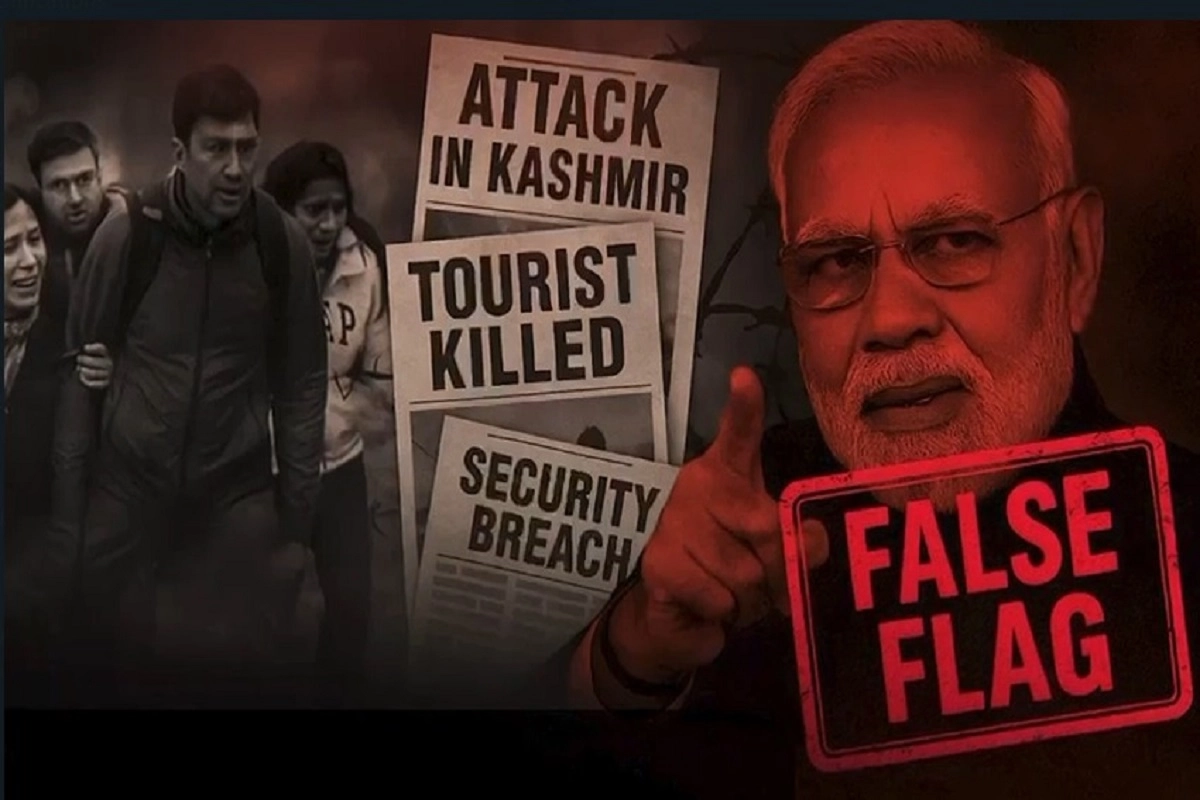

The term “warmongering” is frequently used in the media, and it frequently includes language or imagery that extols violence or encourages military action. The presentation of diplomatic issues as justifications for armed confrontation may be done by anchors or panel debates. This has the potential to inflame public emotion and undermine the cohesiveness of society. Analyzing whether the content is likely to inspire violence or hatred against a group, or whether it is likely to disturb public peace, is the method that is used to determine the boundary between contentious debate and criminal provocation.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators ) contact@legalmaestros.com.

Regarding the provisions of the criminal law that address hate speech and incitement

The Indian Penal Code contains specific sections that can be used to punish speech that incites hostility or public disorder or disturbance. Any individual who, via their words or actions, promotes “disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred, or ill-will between different religious, racial, language, or regional groups” is subject to the penalties outlined in Section 153A of the Indian Penal Code, often known as Indian Kanoon. In a similar vein, words that are intended to “cause fear or alarm to the public” or “incite an offense against the state or public tranquility” are in violation of Section 505(1)(b). Kutchehry in the Court. Not only are these sections cognizable, but they are also non-bailable, which means that the police have the authority to arrest without a warrant, and persons who are prosecuted may be required to demonstrate their innocence.

When a news anchor or station purposefully adopts terminology that incites military confrontation, it may be viewed as an attempt to foment violence or foster enmity between groups. This is precisely the kind of expression that Sections 153A and 505 are intended to discourage. If you are found guilty of violating these regulations, you may face a maximum sentence of three years in prison, a fine, or both. Language that incites hostility is not only unethical, but it also has the potential to violate the law.

The Cable Television Networks Act comprises the regulatory framework.

Beyond the realm of criminal law, the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995 is the primary legal framework that governs broadcasting in India. All cable-transmitted programs are required to adhere to a “Programme Code” that is defined in Rule 6 of the Cable Television Networks Rules, 1994 Indian Kanoon, as stipulated by Section 5 of this Act. Broadcasts are not allowed to “contain criticism of friendly countries” or information that is “likely to encourage or incite violence” or “promote anti-national attitudes,” according to Rule 6 of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. In accordance with Section 20 of the Act, any violation may result in warnings, the suspension of transmission, or even the cancellation of a channel’s license.

When a television conversation not only criticizes a neighboring country but also urges for an aggressive strike, it crosses the line into “incitement to violence,” which is a violation of the Programme Code. It is within the authority of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to issue show-cause warnings and to restrict certain broadcasts. As a result of the fact that enforcement is typically reactive and post-facto, potentially harmful content may continue to be broadcast on television until after the wrongdoing has occurred.

Regulatory Self-Government: The NBDSA Code of Ethics

Private broadcasters in India are required to adhere to the Code of Ethics and Broadcasting Standards established by the News Broadcasting & Digital Standards Authority (NBDSA). These regulations are in addition to the limits imposed by the government. The NBDSA has the authority to punish channels, subject them to penalties, and demand public apologies, despite the fact that compliance is optional. The content that “incites violence” or “promotes anti-national attitudes” is expressly prohibited by the organization’s Code of Ethics, as reported by Telegraph India. Big networks like Times Now Navbharat and News18 India have been chastised by the National Broadcasting and Development Services Authority (NBDSA) for airing programs that “spread hatred and communal disharmony,” according to Outlook India.

It has been made clear by the National Broadcasting and Development Services Authority (NBDSA) that even if anchors present demands for military aggression as opinions, they are not allowed to stir up public worries or instigate violence. Indicating that self-regulation, despite its flaws, has the potential to enforce industry discipline, channels that have been found to be in violation have been instructed to remove content that is deemed undesirable and to pay fines.

Interventions by the Judiciary

In addition, the courts have intervened. Following the conclusion of the Sushant Singh Rajput case, the Bombay High Court criticized media trials and “sensationalism” for violating the Programme Code and putting Hindustan Times in danger of being held in contempt of court. The court decided that no report should be used to harm the interests of individuals who are being investigated or to take advantage of delicate cases in order to come out on top of competitors. In light of this significant ruling, the judiciary has reinforced its position that the freedom of the media is accompanied by a commensurate obligation to avoid reporting that is unfair or offensive.

Another significant intervention was brought about as a result of a Public Interest Litigation that was filed in the Bombay High Court (PIL No. 92252 of 2020). In this case, the court ordered private satellite channels to adhere to guidelines that were based on Press Council norms until a framework that was especially designed for television was established by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Even though these orders are restricted to certain contexts, they demonstrate the judiciary’s desire to ensure that responsible broadcasting is carried out.

Striking a Balance Between Responsibility and Press Freedom

The freedom of speech and expression is guaranteed by the Constitution, namely in Article 19(1)(a), and this protection applies to the press. Article 19(2), on the other hand, grants permission for “reasonable restrictions” to be imposed for the purpose of ensuring “public order” and “security of the state.” When broadcasters substitute nuanced speech with jingoistic sloganeering, they run the risk of crossing the line from protected expression into unlawful provocation or defamation. In order for journalism to be regarded as responsible, it is essential to be truthful, impartial, and aware of the potential consequences that may result from the words that are delivered to large audiences.

The Way Forward and the Obstacles That Need to Be Conquered

Despite the fact that there are laws and codes that are explicit, there are still gaps in the enforcement of these standards. In many cases, regulatory bodies do not possess the power to do monitoring in real time, and the implementation of legal remedies is often a slow process. In order to achieve high television rating points (TRPs), commercial forces drive sensationalism rather than dispassionate analysis. This is done in order to achieve the desired results. It is still rather uncommon for criminal statutes like Sections 153A and 505 to be prosecuted during the legal process. In circumstances involving the media, it is difficult to prove mens rea, which is the legal idea of criminal intent. This is one of the reasons why this is the case.

In order to enhance accountability, India need a media regulator that is both competent and independent. This regulator should have the authority to take rapid action and should be forced to conform to self-regulatory norms under mandatory conditions. The ability to critically evaluate persuasive speech is something that may be taught to people who take part in programs that teach media literacy. Broadcasters should make investments in teaching anchors about ethical standards and reporting that is sensitive to conflicts. This is a major step from the broadcasting industry.

Remarks to Conclude

When news organizations indulge in warmongering, they are not only participating in sensationalism; they are also putting the peace of the general people in jeopardy and straining the bonds that strengthen international relations. There are a variety of safeguards that are included in Indian legislation in order to avoid incitement and foster responsible journalism. These safeguards include criminal fines for hate speech, statutory broadcasting requirements, self-regulatory codes, and judicial oversight. To maintain the right to freedom of expression while also restricting the misuse of media influence, it is vital to have vigilant regulation, ethical self-restraint on the side of broadcasters, and an informed audience that is prepared to reject irresponsible narratives. All of these things are equally important.