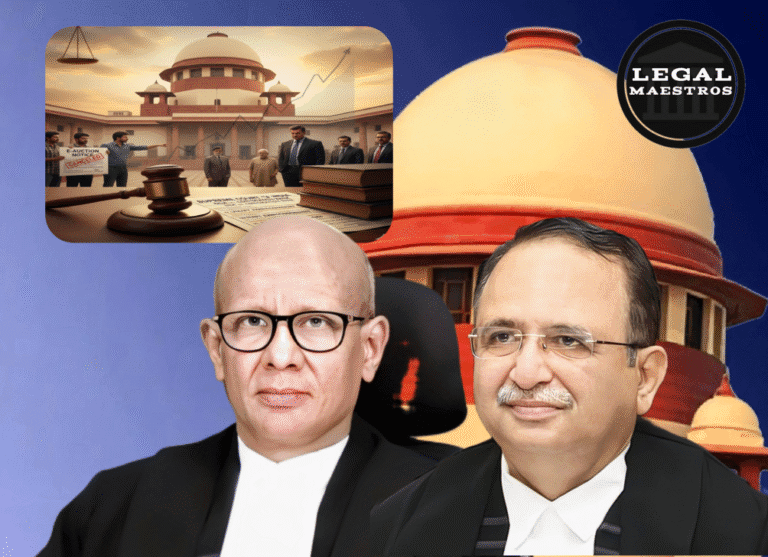

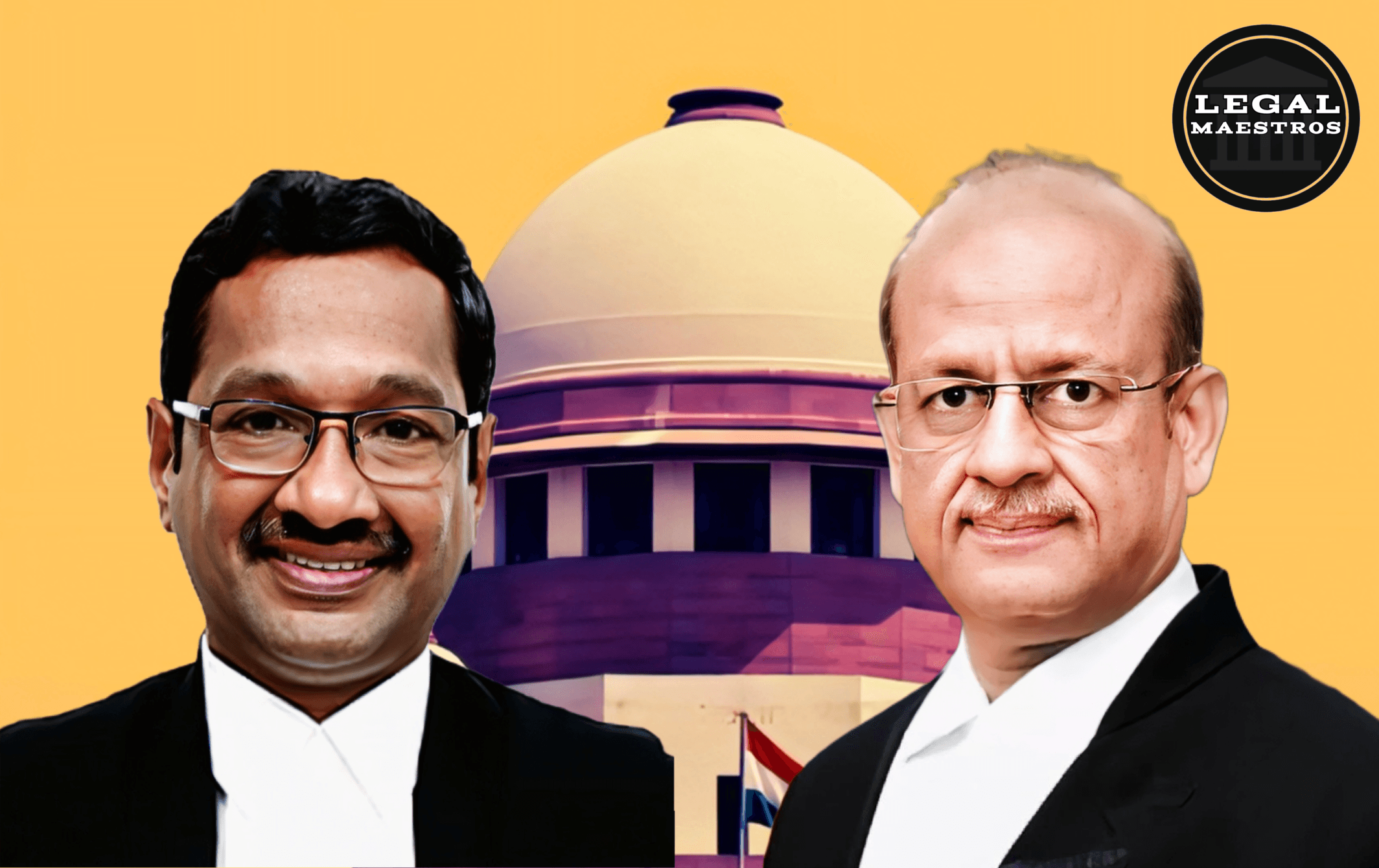

Recently, the Supreme Court of India has passed an important case which dealt with the complex scenario of the interplay between administrative measures undertaken by banks in declaring an account as a fraudulent account and thereafter by undertaking criminal prosecution. This case, which is the result of a bundle of appeals, was determined principally by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and against Surendra Pathwa and others. And intended to illuminate the mandate of High Courts with regards to quashing First Information Reports (FIRs) and similar criminal cases. The Court whose members consist of Justices M.M. Sundresh and Rajesh Bindal carefully made a distinction between the two proceeding types and once again stated that the nullification of an administrative act does not always overturn a criminal investigation.

The Historical and Factual Background of the High Court Census

The genesis of these appeals is on the master directions on frauds issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on July 1, 2016, about the frauds classification and reporting to be done by commercial banks and selected Financial Institutions. These Master Directions were initiated to have a platform whereby banks would detect and report any frauds at an early stage to enable a timely response. Appellant Banks had followed these instructions and as such, it took administrative measures to declare the bank accounts of some companies as fraudulent. Such a declaration had huge civil implications for the respondents as per Master Directions. Moreover, consistent with the damage to the need for the Master Directions to refer some categories of fraud to the State Police or the CBI, criminal prosecution was also launched against the respondents.

Offended by such acts, the respondents presented themselves before diverse jurisdiction High Courts, where they were aimed at questioning such Master Directions as well as questioning what was done to them. The High Courts have used impugned orders in not only quashing administrative actions, but also quashing the registered FIR and consequent criminal proceedings. Their major ground for suppressing the administrative action was the judgment decision of the Supreme Court, which had happened previously.

I. State Bank of India etc. v. Agarwal, Rajesh and Others (2023).The High Court held that the administrative measures went against those of natural justice, namely

Audi Altarem Partem (the right to be heard), the concerned respondents were not accorded a chance to appear before their multi-million accounts and were said to be fraud or blacklisted. Accordingly, the criminal cases were quashed too, and the High Courts considered the criminal cases a mere natural consequence of the other invalidated actions taken administratively.

The arguments that were made in front of the Supreme Court

The Solicitor General and the Additional Solicitor Generals, learned on behalf of the Appellant-CBI, argued that the High Court had mistaken in likening administrative proceedings to a criminal proceeding. They pointed out that civil or administrative action functions on a distinct legal basis with respect to criminal action. It was submitted that in certain cases the quashing of the FIR and the consequent criminal prosecution was wrongly quashed despite the absence of any particular prayer to that effect. Moreover, about cases in which, even acting as a necessary party, they were neither heard nor even impeached as a respondent by the High Courts, the CBI referred. Essentially they contended that the High Courts had gravely misinterpreted the

Rajesh Agarwal’s decision.

On the contrary, the defending senior counsel and counsel to the respondents argued that the High Courts were right in interpreting the meaning.

Civil judgment No. 23 of 2000 by Rajesh Agarwal. They said the criminal proceedings were a direct manifestation of administrative proceedings initiated under RBI Master Directions. It is first of all against the violation of

In the administrative activities, the High Courts were right in striking down the FIRs as well as the criminal cases that were filed thereafter under Audit Altarem Partem.

Criticism and problems with the Supreme Court

After putting the facts of both sides of the case, the Supreme Court directly answered the basic question about the nature and extent of the matter of administrative actions under Master Directions as against criminal actions. The Court categorically said that there is a distinct difference between the two. The regulatory measures are to be enforced by the RBI and the complainant banks whereas instances of criminal action are the responsibility of the CBI. The Court maintained the same position by stating,

The case of Rajesh Agarwal, which pointed out that the issues of administrative action and criminal proceeding are of distinct standing.

Important here is a point made by the Court that making an FIR, undertaking cognizance of an offence is only an activation of the law. Such criminal case initiation does not rely on any administrative decision which is rendered by another authority. The Court pointed out that although similarities of facts may exist in a case, the non-existence of a valid administrative act does not prohibit registration of a based or otherwise cognizable offense. Where the only condition given is the existence of a cognizable offense (the FIR is registered at this stage Hence, its FIR cannot be sustained without administratively following a step. The Court highlighted the completely different and separate reach and role of these two actions especially when they are conducted by various statutory or non-governmental authorities.

The judgment explained that, though such underlying facts may be common, striking down an administrative action on the basis of technical or legal grounds does notola de la tour.

Rendezvous in the nullification of a criminal investigation. The Court made it clear that it was a question whose investigation should be done by the relevant authorities. Although an administrative order may be quashed because it has not followed a legal necessity, still that fact may be used as the foundation of an FIR. In the eyes of the Supreme Court, the High Court did not understand this difference.

The Supreme Court thereafter ventured into the

The judgment by Rajesh Agarwal corrected the misinterpretation of the High Court. It was a specific reference to paragraphs 37 to 40 and 98 of that judgment. The Court pointed out that

Rajesh Agarwal makes it very clear that natural justice cannot be applied when reporting criminal activity. The Supreme Court has always continued its argument in this behalf, and earlier decisions have stressed that without a hearing on the part of an accused, any action in a criminal case would be frustrating in the sense that it would defeat the end of justice.

Whilst noting that the procedure of classifying an account as fraud under the Master Directions is administrative and that

Audit Altarem Partem is applicable also to administrative acts leading to civil effects and in this respect the Court stressed that it is applicable to administrative classification, not to criminal denunciation.

Rajesh Agarwal clearly points out the fact that, “There is no need to hear a person before an FIR is lodged and registered.” The penal and civil implications, including inability to enter institutional finance, which makes the hearing in an administrative context necessary, are independent of registration of a criminal case.

The Supreme Court also chided the High Courts that such quashing of FIRs and criminal proceedings by them was excess of jurisdiction as it either did not make any challenge to the proceeding or afforded the CBI a chance to be heard or not even an opportunity to implead the CBI as a respondent. It also explained that an administrative action cannot be struck down on the ground of violation of natural justice but the administration authorities can re-act after following the tenets of natural justice. Citing

State Bank of Patiala and S.K. Sharma

(1996) and

The case of Canara Bank v. The Court again recalled (Debasis Das 2003 ) that on the setting aside of an order on the ground of violation of natural justice the proceedings are not ended but it only results in vacating the per se flawed order and fresh proceedings lie open.

The Direction and Case Classification

According to its discussion the Supreme Court overturned the impugned judgments of the High Courts. To be able to bring light and simplify the disposition of the many appeals the Court resolved them into five separate groups:

Class 1– HC Challenged and Set Aside FIR. The Supreme Court in such situations would send back the petitions to the High Courts reviving their entire form and in all aspects, except those already adjudiced by the Supreme Court itself. Criminal cases that were quashed, as well as FIRs, will also be restored. These were to be disposed of within four months of the High Court.

Category 2: FIR Complaint Not Contested and Still Quashed by the High Court. In these cases, the Supreme Court quashed the impugned judgment and gave the respondents time of two weeks to use the available provision of law. The only exception to this is the issued that has been ruled by the Supreme Court. The cancelled FIRs and criminal cases will be renewed. Importantly, the respondents will have to make the Appellant-CBI a party-respondent in cases where they will be taking legal recourse.

Category 3A: Date on which the High Court Ordered Interim Orders to continue. Where interim orders have already been passed by the High Courts, such orders shall continue until the petitions are disposed of after remittance to the High Court.

Category 3B: The High Court not having passed an interim order. And, in those cases in which interim orders were not passed, the Supreme Court ordered that no coercive action should be taken against the respondents within a time of two weeks of the passing of the decision by the Supreme Court.

Category 4A: Investigations Under Way. In matters where investigations are under way the Supreme Court has stated that the investigation is to be kept pending but no coercive action against the concerned respondent and accused shall take place during this period.

Category 4B: The investigation has been played out. When the investigation so carried out is complete the Supreme Court ruled that no coercive measures need to be taken or even arrest the concerned respondents/accused.

Category 5: CBI not joined as a Party Respondent Before the High Court. In the present case and in every other case of such nature in the appeals, the Supreme Court to moto issued a directive that the petitioner-CBI be impleaded in the High Court as their inclusion and presence is necessary in light of the remittal to be given fresh consideration. In such cases, permission was also granted to file Special Leave Petitions.

The effect of the judgment of the Supreme Court is also a decisive explanation of the specific character of the administrative act of the bank and criminal prosecution within the definition of fraud cases. It is very well settled that procedural deficiencies in administrative proceedings, including the absence of a prior hearing, do not ipso facto render a criminal investigation or an FIR invalid. The decision echoes the law that registration of an FIR is an independent judicial process of its own fuelled by the cognizance of an offence. Having put the judgments of the High Courts on hold and with a lot of care and diligence and detail as to the classification of the appeals and the remitting of the cases, the Supreme Court has shown the clear way that the legal process should be followed and given extra focus to the independence of criminal law enforcement coupled with the due process that should ultimately be followed in administrative proceedings. The decision is a big boost to banking institutions and those who are charged with the offense of fraud as it avails clarity in law that had been clouded by many branches of judgments.