Under the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), 1908, the Supreme Court of India provided clarification on a significant procedural rule in the case of Nafees Ahmad and Others v. Soinuddin and Others. This case is considered to be a landmark decision.

During the process of deciding initial appeals, the Court addressed the question of whether or not it is required for appellate courts to construct points for determination in accordance with Order 41 Rule 31 of the Complete Procedure Code.

This decision corrects the approach that was taken by the Allahabad High Court and highlights the significance of interpreting procedural rules in a manner that is both flexible and reasonable.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

A Concise Review of the Situation

This case was brought about as a result of a civil appeal that was lodged against a verdict that was handed down by the Allahabad High Court (Lucknow Bench) on September 4, 2017. Remitting the matter to the First Appellate Court, the High Court had largely granted permission for a second appeal with certain conditions attached.

The explanation that was provided was that the First Appellate Court had failed to formulate the necessary points of determination in line with Order 41 Rule 31 of the Complete Procedure Code. Due to the fact that the appellants were unhappy with the remand, they contested this explanation before the Supreme Court.

Provisions of the Law That Are Involved: Order 41 Rule 31 of the CPC

The basic components that must be included in a decision issued by an appellate court are outlined in Order 41 Rule 31 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The document stipulates that the decision must be written down and must include the following:

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Here are the factors that will determine

In regard to those points, the decision

The factors that led to such a choice

Relief that is given in the event that the decision is overturned or modified

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Having this criterion in place guarantees that the rationale of the appellate court is understandable and permits meaningful scrutiny in the event that it is challenged further.

At the Supreme Court’s Present, the Issue

It was requested that the Supreme Court make a decision about whether or not the whole judgment of an appellate court is rendered illegal due to the fact that it did not comply with Order 41 Rule 31, notably the failure to officially frame certain grounds for assessment.

In its decision, the High Court took a severe stance, stating that the framing of such elements was obligatory, and the lack of such framing renders the ruling completely invalid.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The appellants, on the other hand, claimed that this strict reading was not in accordance with the purpose of procedural law, which is to promote justice rather than to undermine it on technical grounds.

The interpretation provided by the Supreme Court

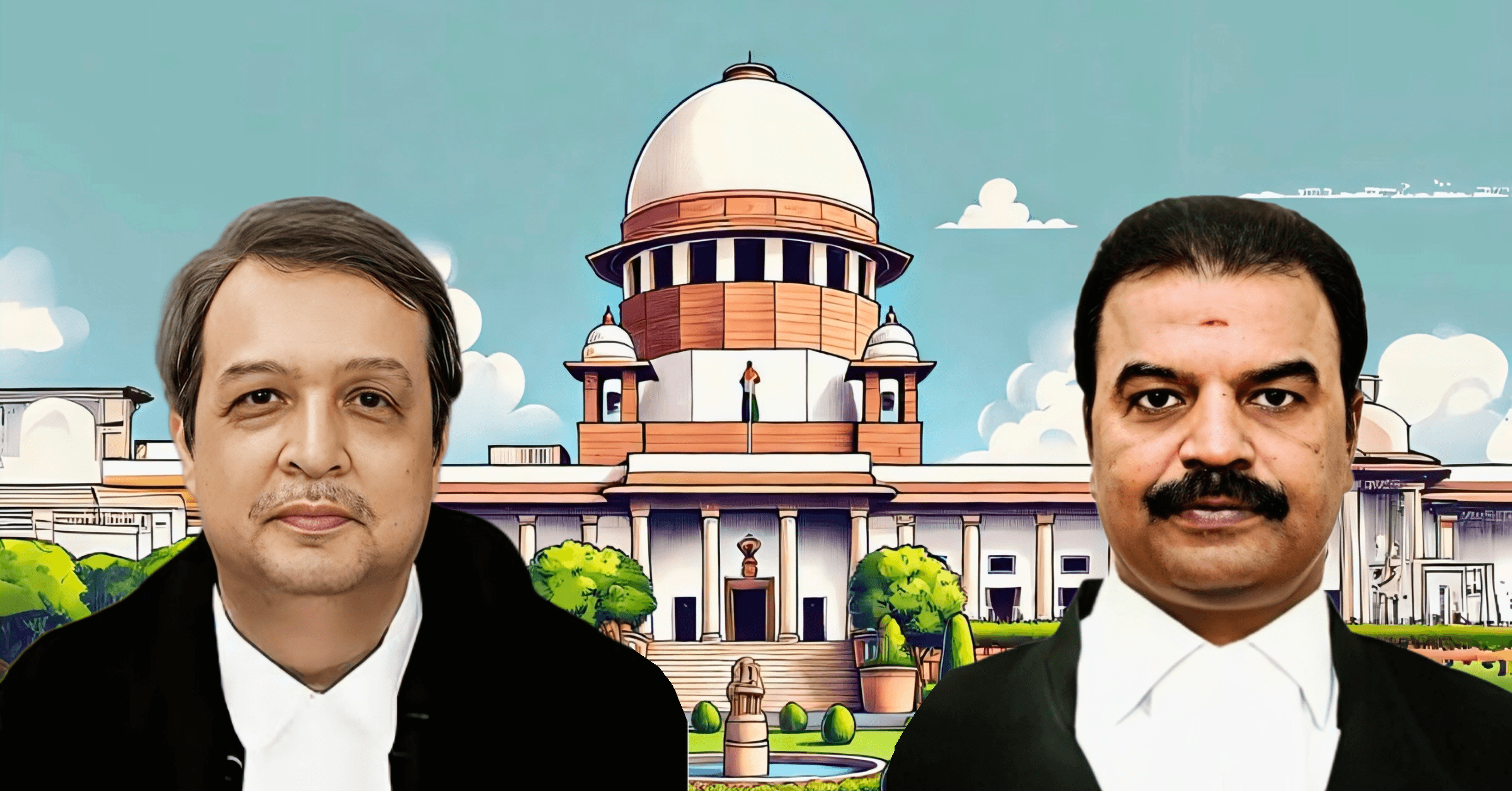

A perspective that was held by the High Court was not shared by the Supreme Court. It was highlighted by the bench, which was comprised of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan, that the interpretation of Order 41 Rule 31 CPC ought to be fair and flexible. Using previous decisions from the Supreme Court and the Privy Council, the Court came to the conclusion that:

It is sufficient to comply with Rule 31 in a comprehensive manner.

The absence of formal points in a judgment does not always render it invalid provided the reasoning and decision-making underlying the conclusion are understandable.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Before making a decision about whether or not the framing of problems was required, the appellate court must first determine whether or not the appellant has brought forward any particular grounds of dispute.

Adherence to Previously Concluded Decisions

The court cited the decision of G. Amalorpavam v. R.C. Diocese of Madurai (2006), which said that the determination of whether or not there is significant compliance need to be made on a case-by-case basis with each individual instance.

In the event that the fundamental reasoning and conclusions are there, the absence of formal framing does not render a decision null and void.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In addition, it referred to the judgment that was made by the Privy Council in the case of Mt. Fakrunisa v. Moulvi Izarus, which highlighted that the appellant is the one who is responsible for demonstrating why the decision made by the trial court should be changed.

A similar observation was made by the Supreme Court in the case of Thakur Sukhpal Singh v. Thakur Kalyan Singh (1963), which said that it is the responsibility of the appellant to demonstrate that the verdict of the trial court is erroneous.

Only when this has been accomplished does the appeal court need to record extensive reasons or define specific questions.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Sangram Singh v. Election Tribunal (1955), in which the court stated that procedural laws are intended to achieve justice and should not be applied in a technical or strict manner, was another case that the court cited.

The Importance of Rule 30 of Order 41 of the CPC

The Supreme Court resorted to Order 41 Rule 30, which gives appellate courts the authority to determine whether or not to refer to the proceedings of the lower court, in order to provide more clarification and support for its reasons.

This indicates that the appellate court is able to make a decision about the matter without engaging in extensive debate or formally outlining the issues at hand if the appellant has not brought forward any new or significant problems.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In its decision, the Court stressed that this discretion enables the appellate court to consider an appeal in a manner that is both quick and just, without becoming ensnared in the formalities of the procedure.

The ultimate verdict

Taking into consideration the arguments presented above, the Supreme Court granted the appeal. The verdict delivered by the High Court was overturned, and it was determined that the remand order was not required.

According to the conclusion reached by the Court, the judgment made by the First Appellate Court did not include any fatal procedural flaws and had essentially met with the criteria of Order 41 Rule 31 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Regarding the Importance of the Decision

This ruling represents a significant step forward in the evolution of civil process in India. The premise that procedural law is a tool to help justice rather than to block it is reaffirmed by this aspect of the law.

As a result of the Court’s decision to rule that considerable compliance is sufficient, legal proceedings have been spared the unnecessary delay that would have been caused by remands. It guarantees that cases do not take longer than necessary owing to objections that are extremely technical.

In addition, the judgment clarifies the methodology that should be utilized by trial and appellate courts when applying Rule 31. While it is true that the rule should be used to guide the construction of judgments, it is also true that it should not be implemented in a mechanical manner.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In the case of Nafees Ahmad v. Soinuddin, the Supreme Court made a ruling that clarifies the applicability of Order 41 Rule 31 of the Criminal Procedure Code. By urging courts to concentrate on the substance of justice rather than the form, it encourages a pragmatic approach to the administration of justice.

In this ruling, the principle that procedural fairness does not necessitate rigorous formality is upheld. Minor procedural errors, on the other hand, should not be allowed to derail the appeal process in cases where the reasoning and conclusion are both obvious and reasonable.

The lower appellate courts, attorneys, and litigants will find this opinion to be particularly helpful. It will ensure that procedural tools continue to be aligned with the greater purpose of effectively delivering justice.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

![Research Assistantship @ Sahibnoor Singh Sindhu, [Remote; Stipend of Rs. 7.5k; Dec 2025 & Jan 2026]: Apply by Nov 14, 2025!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_s0k4u6s0k4u6s0k4-768x707.png)

![Karanjawala & Co Hiring Freshers for Legal Counsel [Immediate Joining; Full Time Position in Delhi]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Gemini_Generated_Image_52f8mg52f8mg52f8-768x711.png)

![Part-Time Legal Associate / Legal Intern @ Juris at Work [Remote]: Apply Now!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_08_41-PM-768x768.png)

![JOB POST: Legal Content Manager at Lawctopus [3-7 Years PQE; Salary Upto Rs. 70k; Remote]: Rolling Applications!](https://legalmaestros.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/ChatGPT-Image-Nov-12-2025-08_01_56-PM-768x768.png)