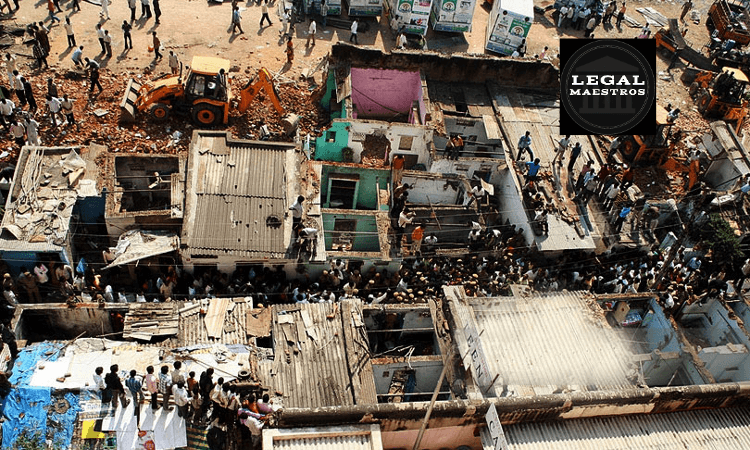

Bombay High Court Upholds Constitutional Rights of Slum Dwellers to Live with Dignity and Safety

Introduction

This article discusses a legal case: NGO Alliance for Governance and Renewal (NAGAR) vs. State of Maharashtra, where Mumbai, one of India’s largest cities with its burgeoning population and rapid development over time continues to face challenges in balancing urbanization, housing, open spaces, environmental protection, the right to shelter, and urban planning regulations as it seeks a practical balance between these competing considerations for the future.

Background of the Case

Their contention is that these slum rehabilitation schemes are being conducted in recreational areas such as parks, gardens, and playgrounds. The Petitioners (predominantly the NGO Alliance for Governance and Renewal [NAGAR]) challenged a 1992 State Notification and Regulation 17(3)(D)(2) of the Development Control and Promotion Regulations, 2034 (DCPR 2034), that allows up to 65% of all public open spaces over 500 square meters to be utilized for slum redevelopment while leaving only 35% for public use.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

NAGAR argued that this type of regulation would enable important public land to be used for something else, which is contrary to the notions of sustainable development and the public trust doctrine, both of which mandate preservation of public resources for all. They pointed out that, in comparison to the 1992 policy, the new regulation made matters worse by reducing the minimum area of land that could be rehabilitated and the amount set aside as a public reservation. The petition stressed the dire lack of open spaces available in Mumbai; per capita availability was shockingly low, far below national and international standards.

The State of Maharashtra, together with the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) and other interveners, supported the regulation by arguing for the practicalities involved in housing Mumbai’s massive slum population, pointing out that previous attempts at eviction and resettlement had failed and that the challenged regulation was a reasonable and equitable way to allow people to remain in their homes while reclaiming some of the land occupied by them to use it as open space (i.e., from “paper parks” to real open spaces). They also argued that DCRs are delegated legislation, which is formulated after extensive public consultation and expert reports, and should not be interfered with so easily by the judiciary.

Fundamental Issues and Provisions Dealt by the Court

To do this, the High Court delved deep into many of the underlying arguments and constitutional amendments, particularly the before-mentioned right to free speech, including:

Constitutional Validity of Regulation 17(3)(D)(2)

The main question was whether Regulation 17(3)(D)(2) is against the Constitution and unfair to citizens because it goes against 14 (Equality before Law & Equal Protection of Laws) and 21 (Protection of Life & Personal Liberty) of the Constitution.

Article 14 (Arbitrariness): The petitioners argued that this regulation would reduce already limited open spaces in Mumbai, which violated their right to a clean and healthy environment under Article 21. The Court accepted the fact that there is an acute scarcity of open spaces in Mumbai and the constitutional obligation to protect the environment but also held that the right to shelter and dignified life and livelihood are all part of Article 21. It observed that the State was under a dual constitutional duty to provide housing for weaker sections as well as protect the environment and concluded that this regulation, which reclaimed 35% of encroached-upon and unusable land for public use by rehabilitating slum dwellers, while being a compromise of sorts, sought to recover part of what has been lost withhad further environmental degradation and converted theoretical open spaces into actual usable areas.

Principles of Environmental Law

You can read the f You can read the full text of the Court’s opinion, which elaborates on the application of the Precautionary Principle and the Public Trust Doctrine, here.

nary Principle: The petitioners argued that the precautionary principle should apply and that any reduction in open space would be presumed unconstitutional unless the State could prove that no environmental damage would occur; however, the Court recognized that this principle is important in environmental law but did not apply it here because it was a policy decision with understood environmental impacts.

Public Trust Doctrine: NAGAR argued that since the State is responsible for managing public resources like open space, taking land for private use (even for slum rehabilitation) would go against this doctrine, so turning functional parks over to private companies for profit would be invalid; however, the Court agreed with the principle but decided this case was different because the beneficiaries were not private developers looking to make money but rather poor slum residents. Regulation met both constitutional requirements of protecting open space (35% retention) and housing, which the Court considered a valid redistribution to further public interest, as long as it is transparent and accountable.

Interpretation of Slum Act Provisions

The petition also wanted to change or remove Sections 3X(a), 3X(c), and 3Z of the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance, and Redevelopment) Act, 1971, which explain who is a “protected occupier” and allow for eviction for the greater good, arguing that these rules were too vague and shouldn’t apply to illegal use of public open spaces. The Court held that these sections perform important social functions and are thus not unconstitutional. It clarified that “larger public interest” under Section 3Z(2) could encompass implementation of Development Plan reservations but stated that in-situ rehabilitation is only a policy guideline, not an absolute rule. The Court held that we can harmoniously construe the statutory framework to ensure the balance between social welfare and planned urban development.

Court’s Approach and Directions

The High Court was pragmatic and balanced by not striking down Regulation 17(3)(D)(2) but issuing comprehensive directions under Article 226 of the Constitution, addressing the core concerns raised by the petitioners: that the 35% open space is designated as public amenity, clearly marked, developed, maintained for all citizens, including rehabilitation residents; a dedicated monitoring committee will be set up with quarterly public reports on development and access to these spaces; there will be an official handover of open spaces to Municipal Corporation through capital grant; no new encroachments are allowed in the reserved open space; GIS-based mapping and geotagging of all open space plots for transparency, mandatory conditions for sanctioning any new slum rehabilitation schemes on reserved open spaces include a certificate of non-availability of alternative land and review by a Special Urban Planning Review Committee; and review of Regulation 17(3)(D)(2) within 24 months to ensure compliance with sustainable development goals. The State is also reminded that it must continue to augment open space per capita in the city.

Conclusion

This case is also significant because it was one in which the Bombay High Court upheld the constitutional validity of a regulation attempting to deal with the complex problem of slum rehabilitation in public open spaces and seeking to balance environmental protection with the right to housing. The legal and policy implications are that even though the government made the regulation to tackle a complicated urban development issue, it didn’t get rid of it but instead set strict conditions and a strong monitoring system; therefore, while policy decisions are mainly the responsibility of the executive branch, the Constitution demands that they consider fundamental rights while working for the public good. The regulation emphasizes transparency, open spaces, and review, suggesting a more active judicial role in making the urban environment more inclusive for all citizens.