In India’s High Courts, legal researchers play an important function that is frequently overlooked by the public. The compilation of case law, the creation of notes, and the analysis of difficult legal questions are all done with their assistance. Nevertheless, the process by which these positions are filled has been subject to examination.

Applicants are often required to go through a brief interview, which may take for as little as a minute or two, rather than being subjected to any kind of written test or formal examination. Such a superficial procedure raises significant concerns regarding the fairness and transparency of the process.

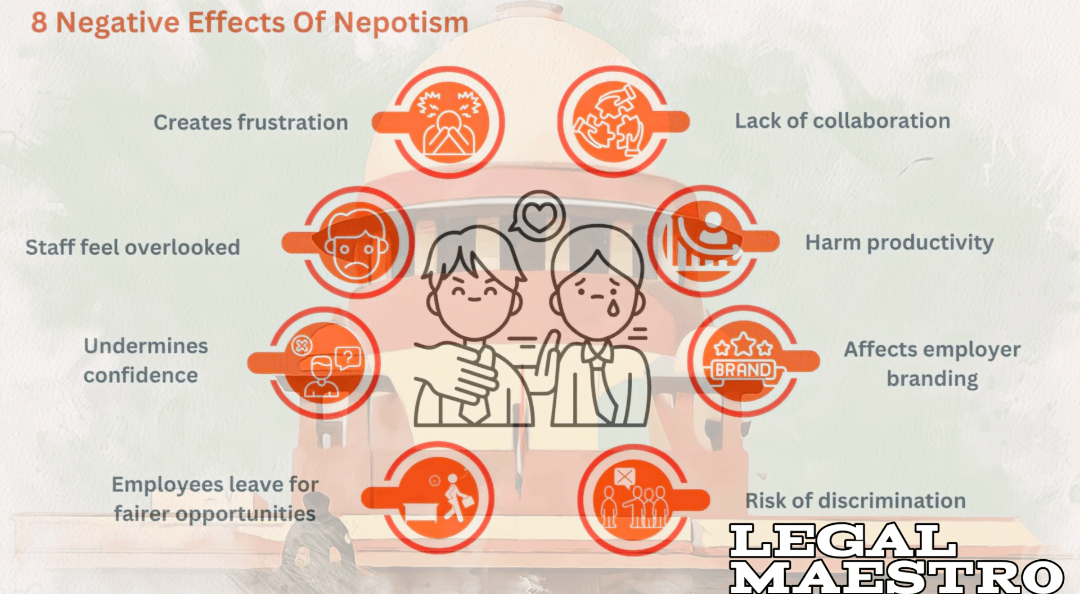

In recent months, lawyers and civil society organizations have expressed their worries that the selection of these essential support staff has been tainted by nepotism and personal bias, which has resulted in worrisome consequences for the quality and impartiality of judicial work.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

A Brief Overview of the Roles of Legal Researchers

In order to provide support for their benches, the High Courts located all throughout India hire legal researchers on a contract basis. Most of the time, these researchers are recent law school graduates or young lawyers who are looking for practical experience.

Among their responsibilities are the preparation of digests of judgments, the performance of extensive surveys of case precedents, and the provision of assistance to judges in the process of complex deliberations.

These positions, despite the fact that they do not provide permanent status, provide valuable experience and a way to get a foot in the door of the legal profession. These kinds of roles have evolved into highly sought-after stepping stones throughout the course of time. On the other hand, there is no standardized, merit-based recruitment structure in place, which stands in stark contrast to the growing demand for these positions. The claims of partiality have taken root within this vacuum, which is where they originated.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

What Are the Problems with the Selection Process?

Generally speaking, notice boards or court websites are the places where announcements for legal researcher employment can be found in High Courts. In the meanwhile, applicants send in their applications and wait for an invitation to an interview.

A brief oral encounter, which is typically carried out by a small panel of court officers, is the focal point of the entire review, which is a surprising fact. In addition to the absence of a case analysis exercise and a structured grading rubric, there is no written assessment of legal knowledge.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

As a consequence of this, the performance of a candidate during a brief conversation carries a disproportionate amount of weight. Interviewers are forced to rely on their own subjective impressions because of the little amount of time they have, which is sometimes just enough to ask a couple of questions. The absence of structure creates an environment in which individual preferences can have an impact on decision-making.

Bias and favoritism in the interview process

On the other hand, some people believe that the lack of objective measures has made it possible for bias and favoritism to develop. A number of individuals who are interested in conducting research have reported that candidates who have familial ties to judges or court officials are given preferential consideration.

It seems that connections, rather than competence, are what make the path to selection easier to navigate. Candidates whose interviews last for a mere two minutes have been selected in some situations, while others who have prepared extensively but do not have access to insider information have been passed aside.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

In addition, the conclusion can be influenced by unconscious prejudices, such as those associated with one’s alma school, one’s regional background, or one’s personal rapport. When interviews are too brief to allow for in-depth questions, even well-meaning panels may revert to using names or faces that are recognizable or welcoming.

Influence on the Judiciary and the Merit System

It is not just individual appointments that will be affected by the consequences of this poor recruitment scheme. The overall quality of legal research may suffer when merit is not the key factor employed in the evaluation process. In order to obtain information that is both reliable and extensive, judges rely on researchers.

The possibility exists that judicial deliberations could be based on briefs that are either incomplete or biased if positions are filled by individuals who are either underqualified or badly motivated. This has the potential to damage public confidence and reduce the effectiveness of the judicial system over time.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The perception that a system gives more weight to connections than it does to capabilities contributes to the creation of larger narratives about institutional corruption. With a judiciary that is tasked with upholding the rule of law, even the appearance of biased recruiting practices can be extremely detrimental to the institution.

Those who speak from the ground

Within the realm of law, there have been some voices that have begun to be heard. In spite of having outstanding academic records, junior advocates who do not have personal relationships in the judicial system express their displeasure at being barred from researcher posts without being considered.

A number of former researchers have expressed their regret because, once they were hired, they saw their counterparts who lacked expertise struggle with fundamental legal research duties. On the other hand, there are a few judicial officers who support the status quo by stating that candidates’ calmness and capacity to think on their feet are evaluated more thoroughly during quick interviews.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

It is their contention that more extensive testing can cause appointments that are urgent to be delayed. In spite of this, many people are of the opinion that any selection process is susceptible to abuse if there are no clear parameters to follow.

A Perspective That Is Comparative

Taking a look at other countries, various common law jurisdictions have procedures that are more stringent for roles that are comparable. In nations such as the United Kingdom and Australia, applications for judicial clerkships are typically required to be submitted in writing, case notes must be submitted, and numerous rounds of interviews are conducted.

For the purpose of evaluating a candidate’s proficiency in legal writing, many states in the United States require moot exercises or written evaluations. These kinds of multi-stage methods serve to ensure that candidates have both theoretical knowledge and the ability to apply that information appropriately.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

On the other hand, India’s High Courts rely nearly entirely on oral impressions, which leaves very little documentation of the reasons why one candidate was selected over another. Due to the absence of accountability, concerns have been further heightened.

Possibilities for an Answer

In order to reestablish faith in the impartiality of the researcher recruiting process, reforming it could be beneficial. The implementation of a straightforward written examination that places an emphasis on legal thinking and drafting would give quantitative criteria.

There is a possibility that arbitrariness could be reduced by establishing explicit grading rubrics and releasing interview questions in advance. To reduce the impact of insider bias and to broaden the range of opinions, it would be beneficial to include retired judges or outside experts on interview panels wherever possible.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Even minimal transparency measures, such as publicly available shortlists or basic score summaries, would deter nepotistic practices. Ultimately, combining oral interviews with objective assessments would strike a balance between testing temperament and ensuring competence.

Reform Obstacles to Overcome

Despite widespread agreement on the need for change, implementing reforms faces obstacles. High Courts operate with limited administrative support and varying resources. Designing and scoring written tests requires infrastructure and coordination.

Judges pressed for time may hesitate to overhaul familiar expedients. Moreover, any move toward standardized testing could encounter resistance from those who benefit most from the current informality. Legal reformers will need to build consensus and demonstrate that even small changes can yield significant improvements in research quality and public trust.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The controversy over short, subjective interviews for legal researcher positions in India’s High Courts highlights a broader struggle between tradition and transparency. While rapid hiring may address immediate needs, it also perpetuates bias and nepotism, to the detriment of judicial quality.

Strengthening the process with objective assessments, clear guidelines, and greater openness can help ensure that the most capable candidates serve the courts. In doing so, the judiciary will not only bolster its research backbone but also reinforce the public’s faith in its impartiality and integrity. As calls for reform grow louder, High Courts have an opportunity to lead by example and set higher standards for merit-based recruitment across the legal system.