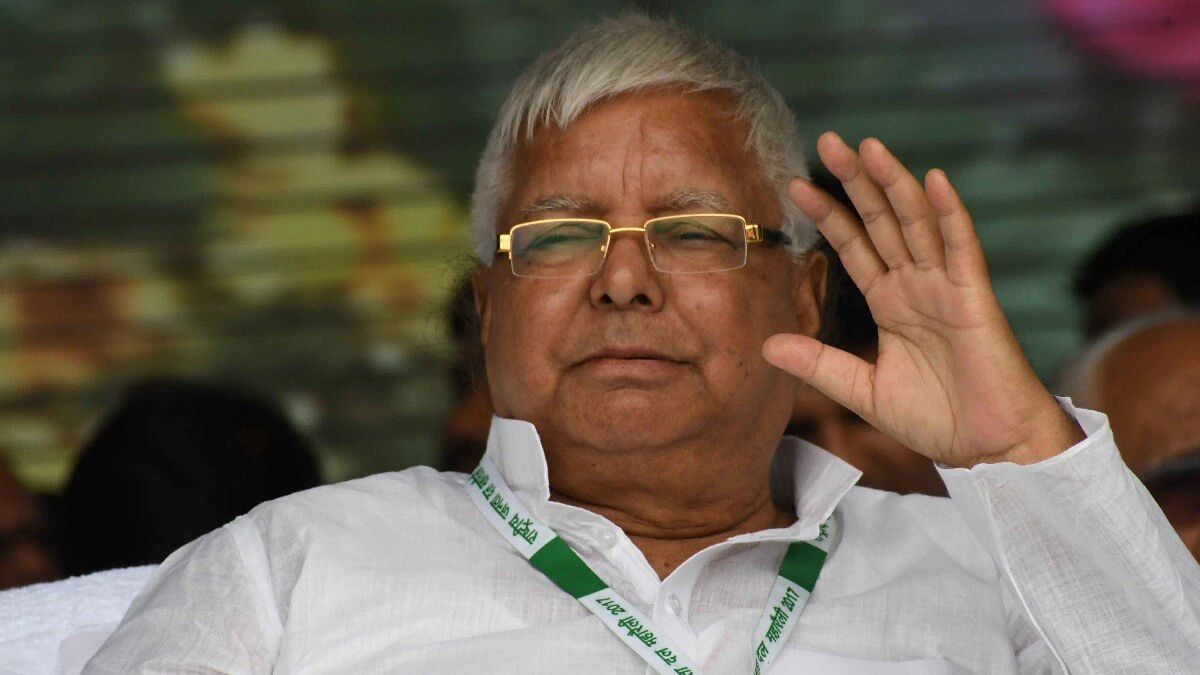

Lalu Prasad Yadav and the Land-for-Jobs Scam : How Railway Posts Were Allegedly Traded for Land Parcels During 2004-2009 Tenure

Introduction

During the time when Lalu Prasad Yadav was serving as India’s Minister of Railways, between the years 2004 and 2009, claims surfaced that land parcels were illegally transferred for railway recruiting seats.

In response to this incident, which has been dubbed the “land-for-jobs” fraud, high-profile investigations have been launched by both the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Enforcement Directorate (ED).

Questions regarding the abuse of ministerial power, the requirements for prosecuting a public servant, and the effectiveness of anti-corruption statutes such as the Prevention of Corruption Act and the newly enacted Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) are at the center of the disagreements that have arisen in the legal battlefield.

Origins and Nature of the Allegations

The suspicions of land-for-jobs were first brought to light by anonymous complaints and admissions made by insiders working inside the Railway Ministry.

It was said that powerful intermediaries arranged for qualified individuals to get junior engineer and other technical roles in the Indian Railways in exchange for minor payments or outright transfers of property to friends of the Minister. This was done in exchange for the candidates’ eligibility to receive these positions.

According to the allegations made by the investigators, residential and agricultural land pieces were purchased at rates that were lower than their current market worth. In return, those landowners or their allies were able to get desirable posts without having to go through the typical competitive tests or background checks.

Despite the fact that the Railway Recruitment Boards (RRBs) are legally independent entities that are tasked with the responsibility of fair selection, whistleblowers reported how orders flowed from the Minister’s office to regional controllers, which resulted in the bypassing of processes that were based on merit.

It is reported that the number of such transactions reached hundreds of postings, which implicated a complex network of officials, contractors, and persons with political connections.

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

The Statutory Framework for the Corruption of Public Servant Positions

For the most part, India depends on the Prevention of Corruption Act, which was passed in 1988, in order to combat the issue of public authority being abused for private benefit.

As stated in Section 7 of the Act, it is a criminal offense for a public official to receive gratification as a reason or reward for executing any public function. This includes pleasure that is not legitimate pay.

The responsibility of Section 8 applies to anybody who provides or offers pleasure with the intention of influencing a public worker. The term “criminal misconduct” is defined in Section 13 to encompass deliberate theft by a public official as well as the acquisition of excessive assets.

In addition, the PCA stipulates, under Section 17A, that no inquiry of a public worker may be initiated without first receiving authorization from the authority that is deemed to be competent.

Statutory Framework for Public Servant Corruption

The new criminal procedure codes, the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) of 2023, have been enacted. Section 218 of the BNSS echoes the previous requirement by stating that the sanction of the president or governor is required in order to prosecute a public servant for actions that were taken while they were performing official duties.

While this procedural protection, which has been maintained in important cases such as K. Veeraswami v. Union of India and State of Rajasthan v. B.L. Meena, shields honest officials against frivolous lawsuits, it also has the potential to postpone responsibility if it is overused.

CBI Investigation and FIRs

In 2018, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) filed its First Information Report against Lalu Prasad Yadav and many allies, including two of his sons and former members of the Railway Board. This action was taken in response to various allegations.

In addition to applicable counts under the PCA for corrupt gratification, the chargesheet charged that the defendant committed offenses under Sections 120B (criminal conspiracy), 420 (cheating), and many other articles of the Indian Penal Code.

According to the investigators, there were occasions in which the RRB sitting lists showed unusual appointments of applicants with sub-par qualifications. These appointments coincided with property transactions that were identified via the offices of the land registrar.

In the beginning stages of the investigation, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) made a request for authorization to prosecute Mr. Yadav under Section 17A of the PCA and Section 218 of the BNSS.

The issue was brought back to life in 2022 when new evidence, which included recorded contacts and bank account traces, verified the quid pro quo.

This occurred after an original closure report was submitted by a lesser agency. Rejecting procedural concerns, the Delhi High Court allowed the First Information Report (FIR) to stand and asked the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to file charges against all of the identified defendants.

Enforcement Directorate’s Money Laundering Case

At the same time, the Enforcement Directorate initiated legal action in accordance with the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), claiming that the profits of the land-for-jobs scandal were laundered via shell firms.

It was discovered by the investigators that shell companies, such as A K Infosystems Private Ltd., were used in order to transfer funds from job-seekers to front corporations that were associated with Mr. Yadav’s family.

In its chargesheet, which was several thousand pages long, the ED listed members of the family, including Rabri Devi and her daughters, and made allegations that they had acquired real estate assets worth crores of rupees via the use of contaminated cash.

The President of India issued approval for prosecution under Section 197(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code (and its equivalent, Section 218 of the BNSS), which made it possible for both the Central Bureau of Investigation and the Enforcement Department to go forward with criminal proceedings.

This was a significant event. As stated in Veeraswami and later opinions, a court would not be able to trial a sitting or former minister for activities that were carried out in the course of their official duties if this sanction was not in place.

Judicial Proceedings and Key Hearings

Lalu Prasad Yadav filed a petition in the Delhi High Court against the FIR and the attachment orders issued by the ED, saying that there were procedural errors and an abuse of agency authority.

The concept of Vineet Narain v. Union of India was raised by his legal counsel, who cautioned against unnecessary delays while also emphasizing the need of protecting his basic right to a fair inquiry.

The petitions that sought a stay of proceedings from the trial court were rejected by the High Court during hearings that were opened in May 2025. The High Court determined that there was sufficient prima facie information to sustain further proceedings.

Arguments on the drafting of charges and the asset-seizure report from the ED are scheduled to be heard by the trial court. In order to demonstrate the sequence of fraudulent transactions, the prosecution will depend significantly on documented evidence, such as RRB appointment records, property register entries, phone recordings, and audits of shell companies, according to a number of legal analysts.

In turn, it is anticipated that the defense would investigate the veracity of digital data, question the connection between land transactions and job allocations, and bring to light any violations of the punishment procedure.

Fundamental Issues and Legal Analysis

The contradiction that exists between the necessity to prevent corruption and the procedural safeguards that are afforded to public officials is at the core of the controversy that involves land in exchange for employment.

Even while the punishment provisions of the PCA are essential for protecting genuine decision-makers, they have the potential to impede swift justice in situations where political influences cause approvals to be delayed. With relation to this matter, the reaffirmation of these standards by the BNSS represents continuity rather than change.

Determining the boundaries of ministerial discretion is still another important topic. On the other hand, a Railway Minister has extensive ability to define policies and order investigations; nevertheless, this discretion does not extend to intervention with statutory recruiting.

In a series of cases that have helped shape the legal landscape, the Supreme Court has emphasized that “public office is a public trust.” Deviations made for the purpose of obtaining personal advantage constitute a serious violation of fiduciary responsibility, which necessitates the strict implementation of Sections 7, 8, and 13 of the PCA.

Another dimension is added by the money-laundering aspect that falls within the PMLA. The proceeds of public corruption are classified as “scheduled offences,” which allows for the attachment of assets while the perpetrator is awaiting trial.

The purpose of this preventative measure is to thwart the dissipation of illegal assets; nevertheless, it must be balanced against the rights of innocent third parties and the accused person’s right to property as outlined in Article 300A.

Comparative Perspectives and Deterrence

At the international level, anti-corruption regimes include preventative, punitive, and asset-recovery techniques into its arsenal. The three-pillar strategy that India takes—the Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA) for corruption, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) for money laundering, and new criminal procedural protections under the BNSS/BNS—is essentially in line with worldwide standards.

Nevertheless, the fact that high-profile persons have been prosecuted for decades demonstrates the existence of systemic flaws.

Accelerating accountability might be accomplished by strengthening timescales for punishment determinations and improving audit-based detection within ministries.

In addition, the land-for-jobs case sheds light on the role that civil society and the media play in uncovering intricate schemes.

In order to induce government action, persistent investigative journalism and testimony from whistleblowers played a significant role. Despite the fact that subsequent reforms have been implemented in a variety of ways, the Vineet Narain decision of the Supreme Court created the framework for proactive CBI control by establishing time-bound rules.

Conclusion

The land-for-jobs scam that Lalu Prasad Yadav was involved in continues to be one of the most prominent instances of corruption in modern Indian history. The difficulties of prosecuting political executives, the complexities of punishment requirements under Section 17A PCA and Section 218 BNSS, and the need of safeguarding meritocracy in public recruiting are all encapsulated in this document.

As the cases progress, the judicial system’s stringent application of anti-corruption legislation and procedural protections will decide whether or not the notorious appetites for political favoritism in Indian Railways eventually come face to face with the full weight of the law.

For any queries or to publish an article or post on our platform, please email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.