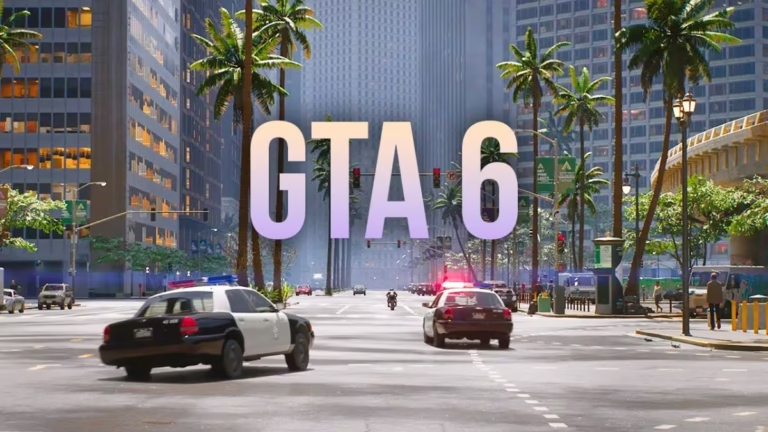

GTA 6 and Public Morality: Examining India’s Obscenity Laws in the Context of Digital Gaming

Introduction

New discussions over the impact of graphic violence and sexual content on public morality in India have been raised as a result of the release of Grand Theft Auto VI. Because video games like Grand Theft Auto 6 combine realistic storyline with interactive gameplay, many people are wondering whether or not the laws that are already in place regarding obscenity can include such digital media. In this article, the legal regulations of India pertaining to obscene material are investigated, landmark judgments are analyzed, and the essay also evaluates how these restrictions apply to contemporary video games. Additionally, it covers the difficulties associated with maintaining morality standards online as well as the requirement for a framework that is specifically designed for gaming content.

Indian Laws Regarding Obscenity

There are two primary legislation that form the basis of India’s legal interpretation of obscenity. On the other hand, the Information Technology Act of 2000 controls digital content, while the Indian Penal Code of 1860 has laws for those that pertain to physical material. The purpose of these acts is to protect public decency and to ensure that vulnerable minds are not exposed to content that could “deprave and corrupt” them. While at the same time, the Constitution of India protects public morals by imposing appropriate restrictions on the right to freedom of expression.

The Meaning of the Word “Obsceny” According to the IPC

The Indian Penal Code, specifically Section 292, makes it a criminal offense to sell, distribute, or exhibit any “obscene” book, pamphlet, paper, drawing, painting, or any other thing. This includes any and all objects. According to the legislation, obscene content is defined as anything that either tends to deprave and corrupt individuals who are likely to view it or the stuff that appeals to prurient curiosity. Section 293 of the Indian Penal Code extends the prohibition to include content that depicts youngsters engaging in filthy behaviors. Acts and songs that are considered to be obscene and are performed in public are subject to the provisions of Section 294 of the Indian Penal Code. However, these laws were created a long time before the emergence of digital culture. They are directed at conventional media.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

As well as the Information Technology Act

In response to the proliferation of the internet, the United Kingdom’s Parliament passed Section 67 of the Information Technology Act in order to restrict the dissemination or publication of offensive content by electronic means. A first conviction under Section 67 can result in a fine of up to two lakh rupees and a prison sentence of up to three years, depending on the severity of the offense. More severe punishments are the result of a repeat offense. The publication or transmission of sexually explicit actions and child pornography are under the purview of Section 67 A and Section 67 B, respectively, which include additional penal provisions. By enacting these provisions, internet platforms are brought within the jurisdiction of obscenity court.

Assessments of Obscenity Throughout History

For More Updates & Regular Notes Join Our Whats App Group (https://chat.whatsapp.com/DkucckgAEJbCtXwXr2yIt0) and Telegram Group ( https://t.me/legalmaestroeducators )

The Hicklin test, which was taken from an English decision in 1868, was utilized by Indian courts for a considerable amount of time. The purpose of this test was to determine whether or not subjects were susceptible to being corrupted and depraved by content. Using this severe criteria, the Supreme Court of India upheld a conviction for selling an unexpurgated novel in the case of Ranjit D. Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra (1965). Within the framework of Hicklin, even single sections may be responsible for rendering a whole work obscene if they possessed a destructive tendency.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

Currently Accepted Standards and Important Cases

As time went on, judges came to the realization that the Hicklin test did not correspond to the shifting social norms. In the case of K. A. Abbas v. Union of India (1970), the Supreme Court of India exercised restraint in its censorship by considering the work in its whole. Aveek Sarkar v. State of West Bengal (2014) was the case that marked the turning point, as it was the case in which the Supreme Court adopted the “community standards” test. This method inquires as to whether the typical person, taking into account the ideals of the modern community, would consider the work to be offensive. The ruling was a departure from the strict moral standards that had been prevalent in the past. Earlier, in the case of S. Khushboo v. Kanniammal (2010), the Supreme Court issued a warning against the use of morality laws as a means of stifling free speech in accordance with Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, with the exception of cases where Article 19(2) imposed restrictions. Within the framework of determining obscenity, these verdicts place an emphasis on context, creative merit, and societal purpose.

Laws pertaining to obscenity being applied to online gaming

For the most part, video games are fundamentally different from books and movies because they need players to actively participate. During Grand Theft Auto 6, the player takes control of characters that engage in sexual or violent acts. Questions regarding culpability are raised as a result of this interaction. Is it possible to hold a game developer accountable for the decisions in-game that a player makes? As a result of the fact that Indian law does not specifically address interactive media, there is lack of clarity on whether the storyline of a game or the acts of a player should be evaluated for obscenity. In the event that games are purchased online or accessible through global servers, it can be difficult to enforce Section 67 of the Information Technology Act, which may apply to digital downloads of games that are considered to be offensive.

The Obstacles Facing the Regulation of Video Games

Regarding the regulation of video games, the existing regulations present a number of obstacles. Firstly, the verification of age on the internet is frequently inadequate, which makes it simple for children to access games with mature ratings. The second point is that due to the worldwide nature of digital distribution, content that is prohibited in India may nonetheless be accessible through platforms located in other countries. Third, the rate of technical advancement is accelerating at a faster rate than the relatively slower process of lawmaking and judicial interpretation. Last but not least, due to the fact that morality is a subjective concept, various groups may have different perspectives on what constitutes acceptable behavior. The disparity between traditional legal frameworks and the realities of new media is brought into focus by these challenges.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Struggle Between Expression and Morality

It is acknowledged by Indian law that the right to freedom of expression is vital, but it is not absolute. Specifically, this freedom is guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a), whereas Article 19(2) permits reasonable restrictions to be imposed in order to safeguard morality and decency. Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015) was the case in which the Supreme Court of India knocked down a vague crime under Section 66A of the Information Technology Act for sending insulting messages. This decision highlighted the need of prohibitions being both clear and proportional. This is analogous to the fact that any regulation of video games ought to be exact and steer clear of arbitrary censorship. The goal ought to be to prevent actual harm without limiting creative expression or the development of technical possibilities.

A Clear Regulation of the Gaming Industry Is Necessary

Given the constraints imposed by the rules that are already in place, India could stand to gain from a specialized framework for video game material. In such a framework, age ratings might be established, specific criteria for content that is deemed inappropriate could be defined, and developers would be required to incorporate parental controls. Certification might be similar to that of films, but it would be suited to interactive media. Compliance might be monitored and complaints could be addressed by a statutory agency or an empowered self-regulatory organization. Taking this strategy would assist protect public morality while simultaneously fostering innovation in the gaming sector. This would be accomplished by giving transparent criteria.

Conclusion

The excitement around GTA 6 highlights the broader question of how India’s obscenity laws apply to interactive digital media. While Section 292 IPC and Section 67 IT Act establish a foundation, they were not drafted with video games in mind. Landmark decisions have shifted the legal test from the rigid Hicklin standard to a community-based approach, allowing for more nuanced judgments. Yet, the absence of clear rules for digital gaming means that enforcement remains uncertain. To safeguard both societal values and freedom of expression, India needs a tailored regulatory mechanism for video games. Such a mechanism would address the unique challenges of interactivity, global distribution, and evolving community standards, ensuring that the law remains relevant in the digital age.

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.