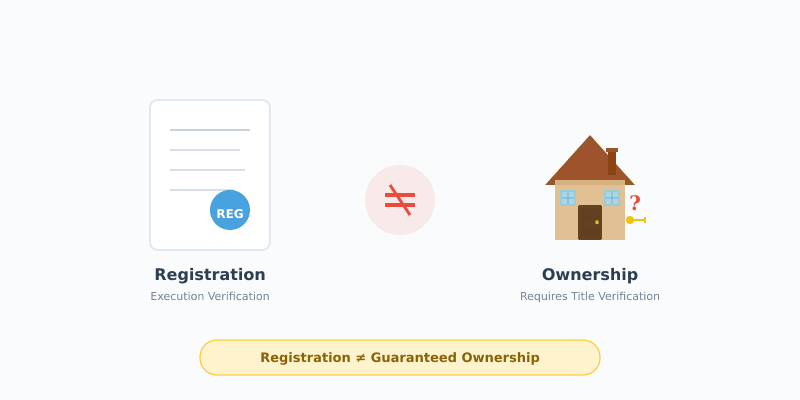

Registration Ownership

-Alind Gupta[1]

One of the most enduring myths about property transactions in India is that registration of a transfer deed guarantees ownership of property. The Supreme Court of India recently reiterated this position and many commentators were quick to highlight how the ruling has ‘rattled buyers and realtors alike.’ This post seeks to clarify the confusion around this far-reaching aspect of property law by looking at what registration actually achieves and more importantly, what it does not.

Understanding the Meaning and Purpose of Registration

For any queries or to publish an article or post or advertisement on our platform, do call at +91 6377460764 or email us at contact@legalmaestros.com.

The Indian Registration Act, 1908 is the law regulating registration of documents in India. Section 17 of the Act provides a list of documents whose registration is mandatory under law. It lays down that, among others, the following documents with respect to immovable property are required to be registered: gift deed, sale deed (if the value of immovable property is more than Rs. 100), mortgage deed, lease deed (if the term is more than 1 year), etc. Section 23 stipulates that these documents have to be presented for registration within 4 months from the date of execution.

Section 34 covers the scope of enquiry conducted by the registering officer before registration. The officer is required to verify the execution of the document. In order to do so, the officer can examine the executants, who are generally mandated to be present at the time of registration. Section 35 empowers the officer to refuse to register the document if the execution is denied or if the purported executant is ‘a minor, an idiot or a lunatic.’

Section 49, one of the most important provisions of the registration law, lists down the consequences of not registering a document that is required to be registered under Section 17. Its relevant part states that the unregistered document shall not ‘affect any immovable property comprised therein, or….be received as evidence of any transaction affecting such property.’ In other words, an unregistered document will not transfer any rights in the immovable property from the seller to the buyer.

Registration of deeds primarily serves three purposes. Firstly, by formally verifying execution, it serves as a proof of execution and limits the possibility of fraud and forgery. In acknowledgement of this aspect, Section 67 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 does away with the requirement of specifically proving the execution of a document if it has been registered (unless execution is specifically denied). Secondly, by maintaining an authentic record of the document, it ‘provides safety and security to transactions relating to immovable property, even if the document is lost or destroyed.’ Thirdly, as registered documents are available to the public, it provides a formal mechanism to obtain information about the property. In fact, Section 3 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 casts a duty on interested persons to look into the registration records before transacting with such property.

What Registration Does Not Do

Registration is geared towards authenticating execution of the transfer deed. It does not go into the question of the transferor’s title. When registering a sale deed, the registering officer does not enquire into the seller’s title, that is, whether the seller actually possesses rights over the property. The Supreme Court has clarified this aspect of registration in unequivocal terms:

“The registering officer is not concerned with the title held by the executant. He has no adjudicatory power to decide whether the executant has any title. Even if an executant executes a sale deed or a lease in respect of a land in respect of which he has no title, the registering officer cannot refuse to register the document if all the procedural compliances are made and the necessary stamp duty as well as registration charges/fee are paid.”

Under the scheme of the Registration Act, 1908, the registering officer is supposed to perform an administrative role, not a quasi-judicial one. The investigation into title of a person is a complex question requiring adjudication by a civil court. This can also help one understand why the registering officer generally cannot cancel a deed after registration.

This reality comes as a surprise to buyers who may face the risk of losing their property despite following all the formalities under the Registration Act, 1908. The confusion partly stems from the fact that registration is seen as the final step in completing a property transaction. While this belief is legally untenable, the underlying concerns are reasonable.

They stem from the fact that India follows a presumptive system of title wherein property documents only create a presumption of ownership. The presumption can be displaced by a person having a better title to the property. The transactions in such a system largely run on the principle of ‘caveat emptor’, wherein the burden of verifying the title of the seller (called ‘due diligence’ in legal jargon) falls on the shoulders of the buyer.

Unsurprisingly, such a system of land titling is laden with issues ranging from uncertainty in property rights, high litigation, benami transactions, etc. Recognising these challenges, the Government is taking steps to move towards a conclusive system of title, which involves the Government taking the responsibility of maintaining accurate land records. Within such a system, the burden shifts from the buyer to the Government, which acts as a guarantor of title. In such a context, the focus of registration would also shift from merely recording the transaction to actually verifying the title. However, until such a system is fully reflected in property laws, the onus remains on buyers to conduct thorough due diligence before acquiring property.

[1] Assistant Professor, School of Law, UPES, Dehradun.

Author’s Linkedin Profile – https://www.linkedin.com/in/alind-gupta-6a4405179